Criterion Collection: Rebecca | Blu-ray Review

“Last night I dreamt of Manderley again,” opens the famous 1938 novel Rebecca by esteemed mystery writer Daphne Du Maurier, astutely mimicked in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film adaptation (his second of three Du Maurier mountings), and announcing one of the most famous openings to a gothic romance narrative in all contemporary English language literature.

“Last night I dreamt of Manderley again,” opens the famous 1938 novel Rebecca by esteemed mystery writer Daphne Du Maurier, astutely mimicked in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film adaptation (his second of three Du Maurier mountings), and announcing one of the most famous openings to a gothic romance narrative in all contemporary English language literature.

The Bronte-esque intersection of class, sexuality, and female agency was Hitchcock’s first foray into Hollywood filmmaking, snagging him his only Best Picture Oscar (plus one of five Best Director nods) and making a star of Joan Fontaine (who would later appear in the 1943 adaptation of Jane Eyre, the prototype for the second Mrs. De Winter).

Featuring several iconic and influential elements, the film remains one of Hitchcock’s enduring masterpieces, and at last receives an updated transfer from the Criterion Collection after languishing in out-of-print status in the label’s archives for many years. Winning two of its eleven Oscar Nominations, it also opened the first Berlin International Film Festival, which took place over a decade later in 1951.

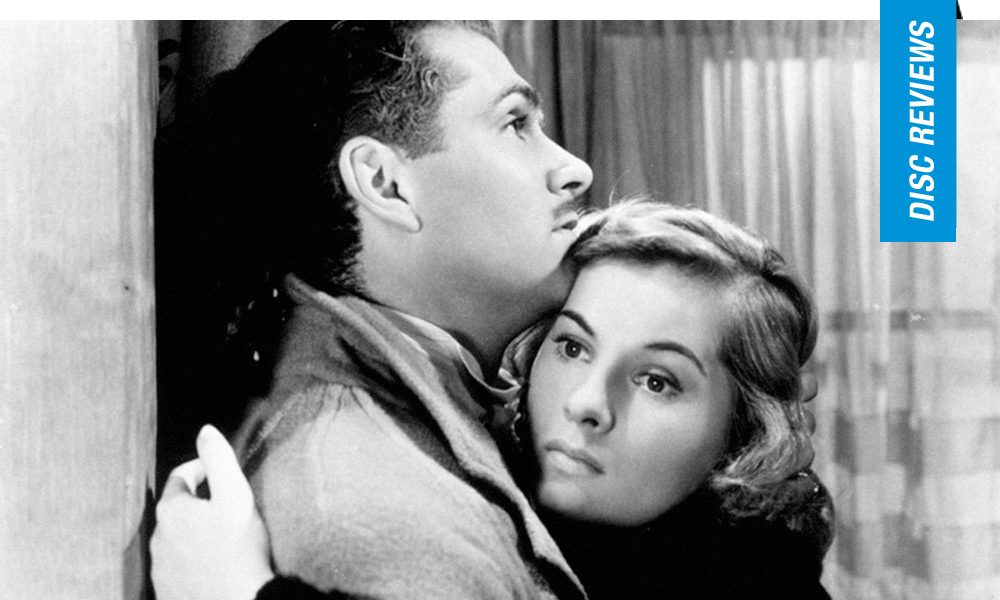

Circumstance allows for a second chance at marriage when afflicted aristocrat Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier), who is mourning the recent death of his first wife, Rebecca, happens to meet a youthful woman (Joan Fontaine) who is serving as the travel companion to the wealthy Edythe Van Hopper (Florence Bates) while all parties are vacationing in Monte Carlo. After a rushed courtship, de Winter whisks the young woman off to his Cornwall estate as his new bride, only to find the palatial Manderley is still more or less dominated by the memory of Rebecca, at least according to the head housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), who seemed to have worshipped her dead mistress. Eventually, dark secrets begin to surface at Manderley as its new Mrs. De Winter begins to take hold.

Rebecca, a noted mix of genre elements, is a melodrama which jaggedly hangs onto a notion of psychic possession, its ghostly eponymous figure haunting the lives of those poor souls at Manderley. What we know of Rebecca is the tortured anguish which her absence has inflicted on those left in her wake, a drowning incident which has scarred her widower husband Maxim de Winter. These towering monikers, including a surname meant to reflect their superior class, are our first telling indications of their natures, including some stark paradoxes. In a historical context, the name Rebecca means not only to tie together, but “to snare,” something her death has certainly accomplished on various levels. A maxim is a general truth or principle, usually rooted in aphoristic tendencies, suggesting the mourning aristocrat’s name means ‘the truth of winter.’ And then, there’s the transparent ingénue played by Joan Fontaine, a woman who is never granted a name, introduced as a traveling companion to the horrid biddy played by Florence Bates and eventually only referred to as the second Mrs. de Winter.

It is Fontaine’s voice-over which glides us into the ‘perfect symmetry of walls’ which made up Manderley, a glorious estate which is no longer, but represents the otherworldly personification of Rebecca, a woman whose home and memory still haunt our narrator even following, we come to find, a sort of second cleansing. Framed as a memory from the perspective of the unnamed woman, we become uncomfortable witnesses to the railroading of an uneasy, naïve young woman as she’s jostled between different masters.

As one of the first of Hitchcock’s films to fully invest in the characterizations (and sometimes caricature) of his supporting players, Rebecca features the key signatures which would come to exemplify his celebrated body of work, from the twinning syndrome, obsessive compulsive tendencies, and a looming architecture which often serves as its own key character. At the forefront is an abrasive but comical turn from Florence Bates as society hag Edythe Van Hopper, a figure who would turn up again in Hitchcock’s textures (a much kinder version of this harping, henpecking womanliness can be seen in the Jessie Royce Landis role of his 1955 title To Catch a Thief). “Men loathe that sort of thing,” she coldly informs her subject, who had tried to interject an opinion into a superficial conversation.

As the narrative progresses, from a courtship which more closely resembles kidnapping, to an increasingly cruel exchange with Mrs. Danvers, the Manderley’s policer of gender/class etiquette and all things Rebecca, Hitchcock offers a number of instances which remain shocking in their 1940 contexts (and is markedly different from his second American film, which would premiere the same year several months later, espionage thriller Foreign Correspondent, which netted Albert Bassermann a nomination for Best Supporting Actor).

Judith Anderson remains one of the most iconic reference points in Rebecca as the chilly, reptilian housekeeper Mrs. Danvers, a woman who drives her new mistress to the point of madness during one of the most infamous moments, the tour of Mrs. De Winter’s pristinely kept bedroom (which includes the caressing of fine undergarments suggesting Rebecca entertained or toyed with the housekeeper’s evident sexual attraction to her). A gatekeeper to what’s now become a nether region, this culminates in Mrs. Danvers, with intense premeditation, coaxing the replacement wife to jump to her death off the walls of Manderley after cruelly tricking her into dressing as Rebecca at a costume party. Forever a letdown, the second Mrs. De Winter is made aware at every turn she has no idea how “to be a perfect lady.”

Obviously not the first or last narrative to suggest its romantic hero is either intoxicated by the memory of another woman, perhaps even a dead one (Preminger’s 1944 Laura certainly attempts a similar suggestion of necrophilia, which also features Anderson). The twist of Rebecca involves the taken-for-granted cultural assumptions we’ve developed involving representations of love and grief, especially as filtered through the perspective of an ‘innocent’ bystander. But suspicions are evident from the beginning of this troubled romance, such as pronounced aural cues, and eventually full blown suspicion which begins to take hold at the jarring presentation of a delightfully perverse George Sanders. Stepping into Manderley through the window, suggesting another violation of Fontaine’s ‘space,’ he introduces himself as Rebecca’s favorite ‘cousin,’ but politely asks his visit not to be mentioned to Maxim (another aggravating request with which Fontaine’s meekness immediately obliges).

Hitchcock’s sparring with producer David O. Selznick, who demanded an adherence to Du Maurier’s novel (not withstanding a change to the ending, commanded by sensibilities of the censors), most likely assisted in the air of tension and anxiety which bleeds out of Rebecca’s foreboding frames (DP George Barnes would also win an Oscar for his work here).

Selznick, as is outlined in David Thomson’s insert essay, was nearing the end of a tumultuous marriage with his wife, and purportedly an affair with Fontaine secured her casting here (she’d win her Oscar a year later in Hitchcock’s Suspicion, but it’s her nameless heroine here which exemplifies the superior performance, although she would lose the Academy Award to Ginger Rogers for Kitty Foyle).

Olivier is in sterling form as the weak-willed widower haunted by the memories of a woman who dominated him (which would mirror Olivier’s own personal life to several degrees, his high profile second marriage to actress Vivien Leigh overshadowing his later union with Joan Plowright, who would reveal some secrets on his sexual orientation), but Rebecca is one of Hitchcock’s strongest femme dominated film, a trio of personalities (one of them dead) haggling for control in a realm where they’re defined solely by their surname.

Disc Review:

Initially, Rebecca debuted in the Criterion Collection back in 2003 as one part of a six-disc Hitchcock collection titled Wrong Men & Notorious Women. But since the label lost the rights for various titles in the set over time, the release became obsolete. Slowly but surely, several titles have returned to the fold and Hitchcock’s 1940 Best Picture winner is now outfitted with a new 4K digital restoration in this Blu-ray two-disc special edition. Presented in 1.33:1 with uncompressed monaural soundtrack, the ghost returns more resplendent than ever. A commentary track recorded for Criterion in 1990 features film scholar Leonard J. Leff, author of Hitchcock and Selznick on Disc One, which also features an isolated music and effects track.

Molly Haskell and Patricia White:

Film critic and author Molly Haskell and film scholar Patricia White are on hand for this interview recorded in 2017 for Criterion. Discussing Rebecca from feminist perspectives, the fascinating, invigorating conversation turns on Second Wife Syndrome and ‘chick lit.’

The Making of Rebecca:

This 2008 documentary by John Cork and Lisa Van Eyssen features Hitchcock’s granddaughter Mary Stone, director Peter Bogdanovich, and several other film historians who studied Hitchcock and Selznick in this twenty-eight-minute examination on the making of Rebecca.

Visual Effects:

Visual effects expert Craig Barron discusses the design and execution of the effects in Rebecca in this seventeen- =minute feature.

Daphne Du Maurier – In the Footsteps of Rebecca:

Elisabeth Aubert Schlumberger directed this hour-long 2016 documentary on the life and work of author Daphne Du Maurier for French television.

The Search for “I”:

Rare footage of screen, lighting and make-up tests, along with notes from Selznick and Hitchcock are included for a wide array of notable actresses who were considered to portray the role of “I,” which eventually went to Joan Fontaine, including Anne Baxter, Vivien Leigh (who famously headlined Selznick’s production of Gone With the Wind, which was still being completed when he began to get Rebecca off the ground), and Margaret Sullavan.

Joan Fontaine and Judith Anderson:

Three excerpts from archival interviews featuring Joan Fontaine and Judith Anderson are included. Fontaine’s bits include a 1980 appearance with Tom Snyder on NBC’s Tomorrow, as well as recording from telephone interviews in 1986 which Leonard J. Leff conducted while researching his book Hitchcock and Selznick. Anderson also is on hand for audio recording from Leff’s 1986 interviews.

Alfred Hitchcock:

Criterion includes this lengthy forty-four interview with Hitchcock from Tom Snyder on NBC’s Tomorrow, which aired November 26, 1973.

Rebecca on the Radio:

Criterion includes three radio version of Rebecca (1938, 1941, 1950). Notably, the 1938 version was adapted by Orson Welles and John Houseman for the Mercury Theater, which stars Welles and was aired only weeks after his infamous War of the Worlds broadcast.

Final Thoughts:

One of Hitchcock’s finest psychodramas, Rebecca’s gothic specter continues to haunt beyond the grave of her creators.

Film Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.