Maestro | Review

The Music Man: Coopers Conducts Intimate Portrait of Leonard Bernstein

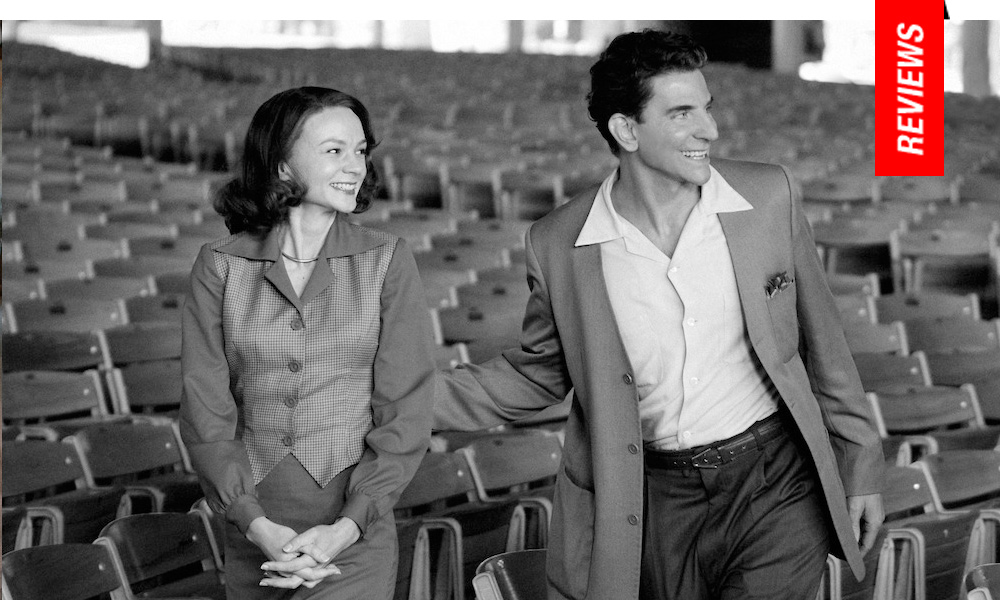

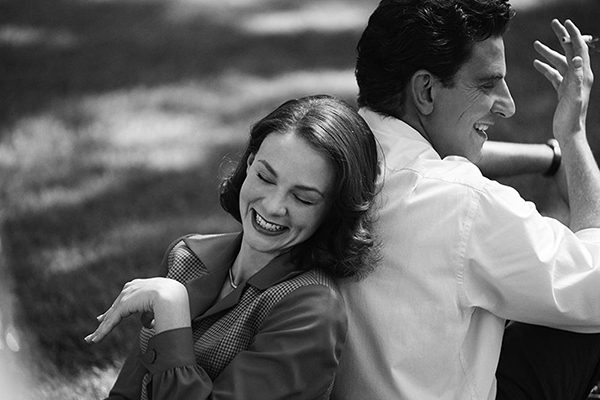

For his sophomore directorial effort, Bradley Cooper maneuvers once again with music in Maestro, an inherently personal portrait of multi-hyphenate genius Leonard Bernstein. Like he did with his 2018 debut, the well-received second remake of A Star is Born, Cooper posts himself from and center as a tortured musician, this time suffering from a different set of cultural expectations, torn between his desires to compose vs. conduct while also living a double life as a gay married man in 1950s America. Opposite Cooper is a graceful Carey Mulligan as his wife, an actress who understands the arrangement but finds herself eventually ravaged by the emotional toll waged by these circumstances. While those unfamiliar with Bernstein’s creative legacy might not fully comprehend the significance of his various artistic achievements, Cooper twirls this scenario into a rather captivating portrait of a marriage catalyzed by social conveniences fostered into a relationship detrimental to the forging of an iconic persona.

For his sophomore directorial effort, Bradley Cooper maneuvers once again with music in Maestro, an inherently personal portrait of multi-hyphenate genius Leonard Bernstein. Like he did with his 2018 debut, the well-received second remake of A Star is Born, Cooper posts himself from and center as a tortured musician, this time suffering from a different set of cultural expectations, torn between his desires to compose vs. conduct while also living a double life as a gay married man in 1950s America. Opposite Cooper is a graceful Carey Mulligan as his wife, an actress who understands the arrangement but finds herself eventually ravaged by the emotional toll waged by these circumstances. While those unfamiliar with Bernstein’s creative legacy might not fully comprehend the significance of his various artistic achievements, Cooper twirls this scenario into a rather captivating portrait of a marriage catalyzed by social conveniences fostered into a relationship detrimental to the forging of an iconic persona.

Opening with Bernstein’s fortuitous conducting of the New York Philharmonic at the age of twenty-five in 1941 (thanks to guest conductor Bruno Walter having the flu), which was the tipping point for his ascension to fame, we focus on his courtship of actress Felicia Montealgre (Mulligan), leading to their marriage in 1951. Before he’s married, Bernstein is pressured to change his Jewish surname if he ever wants to conduct an orchestra, a position which also means he would need to have a private life without blemish. It’s unclear just how clandestine Bernstein is keeping his affairs with men, but as time passes, and three children arrive, his struggles with focusing on composing rather than conducting also plays a hand in the dissolution of his marriage.

Considering Bernstein’s biopic arrives only a year after Cate Blanchett’s exceptional performance as another assertive conducting talent influenced by the maestro, it’s entertaining to imagine how Lydia Tar might have seemed under his tutelage, fighting her way through a sea of ‘doe-eyed boys’ stealing all his attention. For really, what the film grapples with is who or what pulls focus in his life. Cooper attempts to balance these kinds of competing elements in Bernstein tastefully, not shying away from sexually motivated impulses which would have been scrubbed, erased, or demonized had this been made in an earlier era. As such, the film’s second half of the film, its strongest, attempts to pay homage to Felicia, and Mulligan is a masterful tearjerker as the martyred woman who is freed from her conditional marriage too late. In one of the script’s best moments, she confides to her sister-in-law (a finely subdued Sarah Silverman, but still with a playful twinkle in her eye) about how her own arrogance was the real culprit, not her husband’s sexuality. “I fooled myself into thinking what he could give me was enough.”

While much ado has been made about Cooper’s prosthetic nose, it’s really not noticeable at all as we settle into a performance defined by furtiveness, secrecy, and a constant escape from his own self-doubts. Opening sequences feature a lover played by Matt Bomer (with Michael Urie popping up briefly as Jerome Robbins), and his major career milestones popping up in the periphery, with the use of West Side Story’s score utilized, and a brief shout out to his score for On the Waterfront (1954). These early moments are comparable to last year’s My Policeman, and we’re not quite sure how much Felicia really knows until she’s grown tired of her husband’s eventually egregious slip-ups, leading into an agonizing segment where she’s forced to share her family home with the presence of his much younger lover, a student (Gideon Glick).

DP Matthew Libatique switches between black-and-white with the constrictions of Bernstein’s earlier life, graduating to color as he grows into a well-formed personal and professional composite of himself. But Cooper also stays clear of saccharine energy, the kind generated for Cole Porter and Linda Lee’s similar relationship in De-Lovely (2004). Instead, it’s a surprisingly sobering approach to the reality of the situation. Love is shared between them, for sure. But love can’t always be enough.

The dissolution of their marriage is announced to us via a lecture Bernstein gives on Shostakovich, a somewhat egotistical but blunt announcement about how artists, as they face death, need to throw off their restraints and lead the lives they desire. It’s the film’s jumping off point into emotional catharsis, with Bernstein catching up for lost time as Felcia’s resuscitation of her acting career is stymied by a cancer diagnosis, which reunites them during her time of need.

Cooper broadly explores how his infidelity affected his eldest daughter (Maya Hawke), but there’s not much attention paid to the children, or how Bernstein really feels about them. Cooper brings the film to the late 1980s, just prior to his death, who was apparently aware of R.E.M’s track “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine), which famously utilized his name in their lyrics. What we’re left with is a positive portrait of America’s first (and most) acclaimed conductor, who was able to live his best life with the support of a wife whose presence confirmed his heterosexual privilege when it was publicly and privately imperative. But the actual masterstroke of Cooper’s Maestro is when it focuses on the woman whose time and career his own eclipsed.

Reviewed on September 2nd at the 2023 Venice Film Festival – In Competition. 129 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.