3 Faces | Review

Faces, Places: Panahi Provokes the Patriarchy in Quiet Hybrid Drama

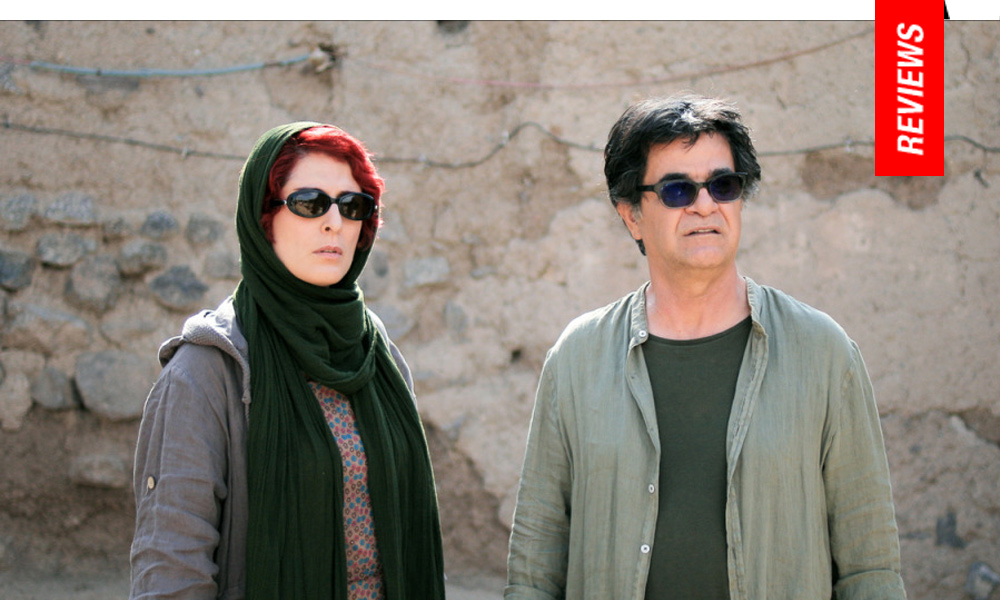

Now nearly half way through his twenty-year ban from filmmaking, (a damning sentence passed down on Jafar Panahi by the Islamic Revolutionary Court in late 2010), the director returns to a semblance of cinema as subversion and subtext with his fourth feature under sanction with 3 Faces. Markedly different in tone than his last three titles thanks to Panahi’s ability to move about freely, his latest effort is a continuation of the auto-hybrid examinations of self vs. society and a return to more effusive glorifications for other cinematic technicians, particularly actresses. If This is Not a Film (2011), Closed Curtain (2013) and 2015’s Taxi (review) were defined by the clandestine parameters with which Panahi was contained by, he’s at last allowed some room to breathe in his cage, taking advantage of his opportunity by embarking on a rural road trip film. Both intelligent and irreverent, Panahi has conjured a calm, clear-eyed scenario examining the subjugation of women and their contradicted agency in Iran’s entertainment industry which may fall short of the art-house accomplishments of his early career but succeeds as another impressive experimental testament of his cinematic rebellion. The handful of main players are all presented as versions of themselves, which lends the film’s staunch seriousness a troubling edge.

Now nearly half way through his twenty-year ban from filmmaking, (a damning sentence passed down on Jafar Panahi by the Islamic Revolutionary Court in late 2010), the director returns to a semblance of cinema as subversion and subtext with his fourth feature under sanction with 3 Faces. Markedly different in tone than his last three titles thanks to Panahi’s ability to move about freely, his latest effort is a continuation of the auto-hybrid examinations of self vs. society and a return to more effusive glorifications for other cinematic technicians, particularly actresses. If This is Not a Film (2011), Closed Curtain (2013) and 2015’s Taxi (review) were defined by the clandestine parameters with which Panahi was contained by, he’s at last allowed some room to breathe in his cage, taking advantage of his opportunity by embarking on a rural road trip film. Both intelligent and irreverent, Panahi has conjured a calm, clear-eyed scenario examining the subjugation of women and their contradicted agency in Iran’s entertainment industry which may fall short of the art-house accomplishments of his early career but succeeds as another impressive experimental testament of his cinematic rebellion. The handful of main players are all presented as versions of themselves, which lends the film’s staunch seriousness a troubling edge.

Marziyeh (Marziyeh Rezaei) stages a dramatic suicide video when her provincial family refuses to allow her to attend Tehran’s drama conservatory, ignoring her desires and instead tricking her into an arranged marriage. The video ends up reaching its intended audience, famed actress Behnaz Jafari, via social media platform Telegram and the distressed actress absconds from a movie shoot to discover if the young girl is indeed dead, alerted of the situation and assisted by director Jafar Panahi. When they reach the girl’s village, they discover the video was merely a ruse to get Madame Jafari’s attention, who is initially displeased to discover she’s been duped. However, once they are introduced to Marziyeh’s abusive family, the patriarchal expectations which Jafari herself transcended thanks to her career forces her to reconsider an empathetic stance, a sentiment further fostered by the presence of another villager, once a renowned actress before the 1979 Islamic Revolution who is now a reclusive outcast on the village’s outskirts.

Playing a subdued version of himself (especially compared to his personas as the centrifugal force in his last three films), Panahi wends an intriguingly demure portrait, implicating his own complicity in the subjugation and repression of women both culturally and cinematically. While occupying the role of the driver/driving force of the film’s dramatic mechanism, Panahi literally takes a backseat to the proceedings in what represents an interesting progression following on the heels of his 2015 Golden Bear Winner Taxi (Panahi would take home a Best Screenplay award following this film’s premiere at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival).

The title 3 Faces is reminiscent of Altman’s 3 Women (1977), a moody, ambient art-house think-piece displaying three females whose personalities are refracted shards of cultural expectations. Here, the three women are tiered generationally, a phantom figure of the pre-Revolution era, shamed into obscurity as the village pariah; a successful, recognizable contemporary actress; and a young girl who uses modern technology to pull a stunt as impetus to realize her creative freedom. They also coincide with subtler themes woven throughout the dialogue pertaining to notions on “losing face,” “saving face,” and the visual representation of “showing face.”

Access equals agency, and the troubled dynamics of the three actresses in 3 Faces points to the contradiction of women as enemy and savior to one another. Marziyeh’s flight to Madame Shahrazade’s modest home puts the older woman in danger of inspiring a village riot—likewise, how the young woman motivates Behnaz Jafari to abandon a film shoot in order to ensure she didn’t commit suicide is as much about damage control for her career than it is to assuage her own emotional malcontent.

Notably, Shahrazade is never seen on film, an invisible fixture of a past no one has the capability of resurrecting. Cinema and the act of filmmaking are likewise used as conduits for truth-telling and discovery as well as false-hood and propaganda, with performance as merely a means for obtaining desired effects from moment-to-moment. “There’s no reason to doubt,” Panahi assures Madame Jafari on their road trip to Marziyeh’s village, the possibility of her death is juxtpoased by a wedding, an event which signals similar consequences for the young girl. Woven into this subtext are more obvious cultural considerations for men vs. women, such as the village elder who relays the history of his lineage to Madame Jafari, giving her the twelve-year-old foreskin of his son to give to director Panah so he may serve as spiritual godfather and influencer of the boy’s future based on superstitious customs. More powerful is Panahi’s inclusion of a crippled bull, whose breeding days have come to an end just prior to a number of “disappointed” heifers scheduled to be carted into the village for insemination. The bull is likened by its owner of inspiring incredible desire in the cows, yet another projection of patriarchal propaganda. It sets up 3 Faces for its most powerful moment, suggesting not only the inherent power of women sticking together, but also the notion of sidestepping the mechanisms of men designed explicitly to hold them back.

While Panahi injects the film with some instances of light humor, 3 Faces is mostly a quiet, arid exercise. And though it skirts around the ostensible desperation of both its filmmaker and its characters, perhaps most importantly it is another instance of tenacity and resiliency in the face of impossible circumstances.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.