Reviews

127 Hours | Review

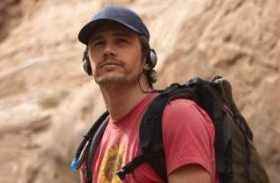

Stuck Between a Rock and …: Boyle’s True Oscar Worthy Pic is Textbook Perfect

127 Hours opens with a montage of international fanfare complete with split screens, fancy camera work, and exciting movie music. This opening continues with the introduction of our hero Aron Ralston (James Franco) getting out of the shower and ignoring his mother’s voice as she leaves a voicemail on his machine. He preps a backpack for a hike, scrounges around his messy apartment for gear and whatnot. Big laughs come when he reaches to a high up shelf where the camera sees his Swiss Army knife, but he does not, and thus leaves it. We all know the story and how that would have come in handy. He drives out by himself to the middle of nowhere, where he promptly goes to sleep in his trunk. The next morning, he repacks, and sets off on his mountain bike. Ralston’s voiceover tells us that it’s a four-hour ride through beautiful and vast red, orange, brown and yellow desert sand and mountain ranges, but he’s going to “knock 45 minutes off that.†It’s all very exciting, especially because of the rock and roll music it’s set to. The bike ride especially is filmed with a whole lot of fancy camerawork and style.

After the highly overrated Slumdog Millionaire, this opening appears ominous. More fully unnecessary panache? More musical montages telling us what emotions to feel and how deeply? More putting the same old stories in new contexts and calling them “original?†Well, 127 Hours ends up having all of that except the unnecessary panache. It has all the same stylistic elements of Slumdog, and obviously other Boyle films, but this time everything works and no technique is overused.

The first part of his trip is decorated with an encounter with the likeliest hikers in the middle of nowhere you’d encounter—Kristi and Megan, played by Kate Mara and Amber Tamblyn, average looking hiker girls, right. The camerawork that seems at first to just be a way to make a bike ride exciting really starts to take control once Ralston is by himself.

After the archetypal horror genre opening of an innocent, idyllic afternoon with some beautiful girls, Ralston goes deep into the canyon, hiking through a very slim passageway at the bottom of a huge drop. We all know what’s coming eventually, and the camera follows him in this frenetic, almost first person way, where we’re nervous at every little turn that that rock might be that rock. From this point on, Boyle meets every challenge that comes with making a film about one guy stuck in one place the entire time. Not only is every moment thrilling, but every detail and stylistic element of the introduction comes back to make sense. The film that is least likely to be cinematic this year is actually the most cinematic one of the year and of Boyle’s career.

The opening gives us a seemingly superfluous, form over function, shot that goes inside of Ralston’s camelback water pack. It looks cool, but it’s questionable why it’s needed, apart from to break up monotonous crane shots of driving, bike riding, and walking. Later in the film though, Boyle reuses the same technique, when the water in the pack is his own urine, which he drinks to survive.

This is spectacular filmmaking. He draws the audience in, makes us comfortable with a certain style. We associate it with something specific, and lock that association comfortably into place in our brain. Later, he uses that Trojan horse to violently break into that compartment of our brain, completely reframing the original reaction and accompanying emotions. This makes the urine drinking scene that much more effective. Had he not set this up with the shots in the opener, it would just be simple shock effects, but Boyle makes it infinitely more effective and rewarding this way.

127 Hours takes such a strange route to the classic A goal, external, and B goal, internal, format. The A goal is obviously GET OUT FROM UNDER THE FUCKING ROCK! Nobody actually expects there to even be an internal goal in this film though, but it’s so powerful that, like the best films, it takes over our attention from even the most succinct, black and white, effective external goal possible.

There are two important ways to discuss the internal goal. First of all, Boyle makes it clear that the internal goal is not a new one, but something that Ralston only discovers the importance of because of the external goal, however, it was there all along. Ralston’s overabundance of self-confidence leading into his selfishness is what got him into this predicament. He ignores those who love him and takes that love for granted. He prefers distancing himself from the world, going hiking in the middle of nowhere, even taking different paths than he’s supposed to, and the worst—not telling anyone.

The second is the form in which Boyle injects this dynamic. The entire form of the film is based on putting us inside Ralston’s head. He uses mixed mediums and many different shooting styles to achieve this, aided by Cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle’s ingenuity with small handheld cameras. Boyle employs POV subjective camera work, Ralston documents his situation with a video camera and talks to the camera, we go into Ralston’s fantasies, sometimes they are obvious, sometimes ambiguous until the end.

The genesis of this project comes from Boyle. He read the book and immediately knew he wanted to make the movie. He told his frequent collaborator producer Christian Colson, but Colson thought it impossible. Same with screenwriter Simon Beaufoy. Then Boyle wrote a six-page treatment that will become infamous. That treatment outlined the entire story as well as the way that Boyle intended to convey it visually. After reading it, they were in.

The idea was to make this story come across as a first person journey. Every effort was made to put the audience in the head of Aron Ralston. The moment that Boyle knew the movie was possible was when read about Ralston talking to the camera. The movie does not really work if there is only Ralston talking to himself, but as soon as that camera comes into play a dialogue is created and thus a story.

127 Hours is a film worth studying for years to come, for it’s a textbook on how to make a story cinematic. Everyone here is at the top of their game. Fox Searchlight has the two top contenders for best picture this year, along with their December release, Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan. It’s possible that The King’s Speech is more fitting for the Academy’s tastes, just in subject matter and writing and acting style, but it does not come close to these two films as far as Boyle’s and Aronofsky’s artistic mastery of the medium.

Rating 5 stars