Reviews

Sal | Review

No Salutation: Franco Resurrects Tragic Mineo to Aimless Effect

Like The Broken Tower, which documents the tragic end of poet Hart Crane, James Franco’s second directorial effort from 2011, Sal, also happens to resurrect an artistic queer figure from the past, this time Oscar–nominated actor Sal Mineo, murdered outside his West Hollywood apartment back in 1976. While the film is finally being granted a theatrical release, Franco has gone on to debut a slew of other directorial efforts, expanding his desire to provoke, titillate and subvert notions of queerness in a broader cultural discourse with items like his co-directed Interior. Leather Bar, and even adapting notable literary works, like Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God. Considering an equally heavy acting schedule, Franco’s output is quantitatively impressive, but quality thus becomes the lack in his exploration of the last hours of the life of Sal Mineo. While the subject is intriguing, Franco’s amateurish rendering would make a marvelous film school project, one that’s neither compelling nor as provocative as it thinks it is.

Like The Broken Tower, which documents the tragic end of poet Hart Crane, James Franco’s second directorial effort from 2011, Sal, also happens to resurrect an artistic queer figure from the past, this time Oscar–nominated actor Sal Mineo, murdered outside his West Hollywood apartment back in 1976. While the film is finally being granted a theatrical release, Franco has gone on to debut a slew of other directorial efforts, expanding his desire to provoke, titillate and subvert notions of queerness in a broader cultural discourse with items like his co-directed Interior. Leather Bar, and even adapting notable literary works, like Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God. Considering an equally heavy acting schedule, Franco’s output is quantitatively impressive, but quality thus becomes the lack in his exploration of the last hours of the life of Sal Mineo. While the subject is intriguing, Franco’s amateurish rendering would make a marvelous film school project, one that’s neither compelling nor as provocative as it thinks it is.

Sal Mineo, the Oscar nominated actor for Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Exodus (1960) was enjoying the beginning of a career resurgence in 1976 after receiving funding for his directorial debut, a stagnant career revitalized after having been stalled by continual typecasting as a troubled teen. Unapologetically open about his sexual orientation, Mineo wanted to adapt Charles Gorham’s novel, McCaffery, a graphic gay themed novel into a film that embraces gay life realistically, with complex characterizations and brutal honesty. With this and a starring role in a new play, Mineo’s path seemed back on track until he was suddenly stabbed to death outside of his home.

Franco’s Interior. Leather Bar (co-directed with Travis Mathews), attempts to recuperate 40 minutes of footage cut from William Friedkin’s notorious film Cruising, and without getting into all the history behind that, it’s interesting to note that Friedkin’s film is cited as the result of a director wholly unfamiliar with the scene he’s attempting to depict. And for all of Franco’s fierce convictions on challenging the status quo, his more potentially risqué directorial efforts reveal similar faults as well as a reluctance to actually push boundaries. A visit to a day spa, over which a forebodingly ambient score plays, becomes one of a number of egregiously banal activities during Mineo’s last day of life.

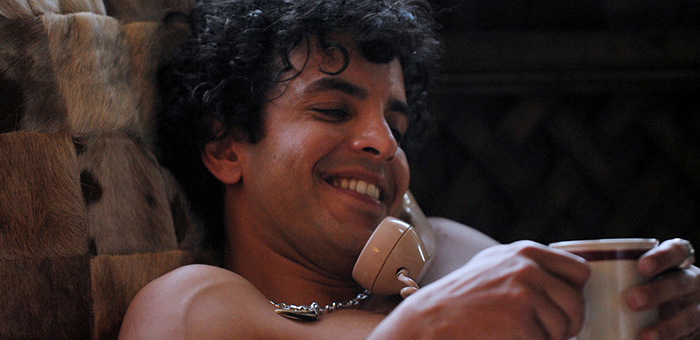

While Franco (and screenwriter Stacey Miller) may not have ever attended a bathhouse with gay patrons (this is 1976, remember), generally a boyish romp in the pool and a non-sexual massage aren’t the only items on the docket. Instead, Franco and Miller save the salaciousness for a conversation between Mineo and his bathhouse buddy, which reveals a verbally graphic recollection of a recent hookup. While the point may very well be that Mineo lived a rather uneventful last day on Earth, Franco’s Sal can’t quite manage to instill any kind of relevance to what we see, instead instilling us with a rather garish tediousness. Val Lauren is filmed often in extreme close-up, as if in some audition for some reality based television project, jostling handheld cameras distractingly following him. While the intent from DP Christina Voros seems to be to make this feel as if it was filmed in 1976, we’re almost always reminded of its attempt rather than its accomplishment.

As for Val Lauren, it would be a disservice to see Interior. Leather Bar, where the actor reveals himself to be a sniveling sycophant at the altar of Franco, before watching his persuasive turn as Mineo, the most astute figure in an altogether unimpressive vehicle. To be fair, Franco does seem to use Lauren as a conduit for representations he’s too unwilling or too uncomfortable with to delve into as an actor. While a rehearsal sequence which sees Mineo playing a bisexual intruder in the play P.S. Your Cat is Dead next to Keir Dullea (Jim Parrack) is rather grating, overall it’s a performance worthy of a better film, perhaps one which would be daring in its assertions behind possible motives of Sal’s killer.

Here, we’re led to suppose that certain aspects of his lifestyle may have had a hand in his death, even as Franco shows Mineo thumbing over Pasolini lobby cards, a queer filmmaker also notoriously murdered after completing the sexually transgressive cinematic film Salo, or 120 Days of Sodom, a hint that maybe the actor’s outspoken insistence on bringing realistic portrayals of queer culture to the masses may have sparked some roundabout cause and effect. The repeated use of Peggy Lee’s obscure “Where Flamingos Fly,” while used too often, lends a haunting flavor to Sal’s sterile actions, but Franco’s treatment is a biopic without a cause. A more interesting endeavor would have been if Franco had picked up where Mineo left off and adapted McCaffery.