Disc Reviews

Criterion Collection: Cat People | Blu-ray Review

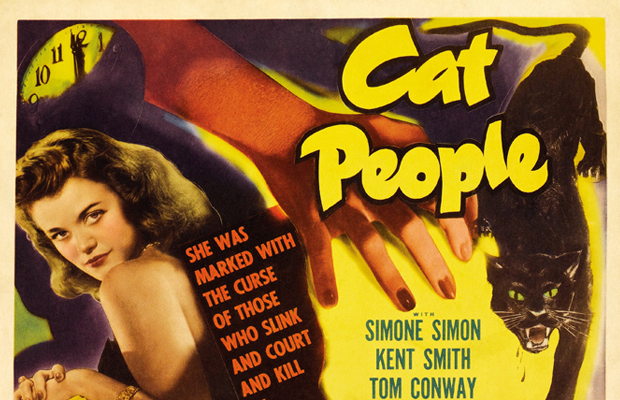

The concept of ‘psychological horror’ is a genre notion all but extinct in modern cinematic renderings of thriller narratives, a once lucrative subgenre considered potent thanks to the adage ‘less is more’ when it comes to visualization of fear and dread. A more contemporary business model of what gets bodies into theaters has little to do with subtlety or psychology, but merely the promise of delivering a balance of anxiety mixed with the quelling of curiosity in having all questions answered and mysteries solved, because who wants to leave the theater confused, angry, or provoked into conversation? Looking back into the annals of genre cinema, a string of titles billed as horror films from producer Val Lewton during the 1940s are still the perfect antidote to special effects driven studio mainstays in American cinema (at the time of their release such films had to contend with comparisons to the franchises Universal Studios continues to reboot today). Out of this independent, cheapie B-movie model, perhaps the most sophisticated creature feature ever made was born, the 1942 thriller Cat People, which was also the first horror film Lewton made for RKO Pictures. Directed by French import Jacques Tourneur (son of silent film director Maurice Tourneur, who would make his last titles the same decade as this redefining genre movement), it’s a film generating suspense based solely on suggestion, its director mastering the technique of contouring shadows and angles, hinting at what’s lurking in the frame, just beyond the strain or squint of the eye.

The concept of ‘psychological horror’ is a genre notion all but extinct in modern cinematic renderings of thriller narratives, a once lucrative subgenre considered potent thanks to the adage ‘less is more’ when it comes to visualization of fear and dread. A more contemporary business model of what gets bodies into theaters has little to do with subtlety or psychology, but merely the promise of delivering a balance of anxiety mixed with the quelling of curiosity in having all questions answered and mysteries solved, because who wants to leave the theater confused, angry, or provoked into conversation? Looking back into the annals of genre cinema, a string of titles billed as horror films from producer Val Lewton during the 1940s are still the perfect antidote to special effects driven studio mainstays in American cinema (at the time of their release such films had to contend with comparisons to the franchises Universal Studios continues to reboot today). Out of this independent, cheapie B-movie model, perhaps the most sophisticated creature feature ever made was born, the 1942 thriller Cat People, which was also the first horror film Lewton made for RKO Pictures. Directed by French import Jacques Tourneur (son of silent film director Maurice Tourneur, who would make his last titles the same decade as this redefining genre movement), it’s a film generating suspense based solely on suggestion, its director mastering the technique of contouring shadows and angles, hinting at what’s lurking in the frame, just beyond the strain or squint of the eye.

Arguably, the narrative couldn’t sound sillier when said aloud, and was the first screenplay of playwright DeWitt Bodeen (who could also write a meaningful dramatic scenario, as evidenced by his work on The Enchanted Cottage and I Remember Mama). Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon) is a Serbian immigrant who meets a milquetoast draftsmen for a shipping company, Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) while sketching a black panther at the zoo one day. She tosses a sketch at the garbage can, but misses, inviting chastisement and an opportunity for flirtation from the man. She professes to be merely interested in the subject of her drawing (professing to be merely a commercial illustrator), not as a true artist (and yet, despite his best efforts, a torn sketch of a panther pierced by a sword is left to flutter in the dry leaves, an imprint escaping censure).

Bodeen’s screenplay is filled with bits of juicy dialogue either erotically charged (apparently she has a peculiar fragrance, something ‘warm and living’ and not like usual women’s perfume modeled after flowers and plants) or downright foreboding. “You looked at me in such a funny way,” remarks the architect as he walks the spritely woman home. Immediately, she remarks he is her first ‘real friend’ in the city. As if this isn’t a budding relationship already peppered with red flags, the two eventually swear their love for one another, which disheartens Oliver’s office mate, Alice (Jane Randolph), who is smitten with him. But all is not well between Irena and Oliver, mostly because she believes the moment they will be intimate, she will turn into a cursed cat creature, an idea she brought with her from Serbia, where historical figure King John drove out the occultists in the country, symbolically represented by a skewered panther on the nobleman’s sword on a prominent bust in her apartment.

Downplaying her irrational fears of intimacy, they get married, despite several provocative moments suggesting Irena is telling the truth (like a creepy visit to the pet store to return a cute kitten whose hackles are raised when Irena is near), and most tellingly, when a fellow countrywoman (Elizabeth Russell) accosts her during a public celebration to call her ‘sister,’ a woman fellow partiers alarmingly describe as cat-like.

Bodeen’s screenplay manages to be subversive even with its plentiful and obvious allusions to Irena’s inevitable transformation into a black panther. The psychological and supernatural ramifications abound, both with Biblical allusions (a zookeeper quotes a swath of Revelations, wherein the good book describes the antichrist as ‘like unto a leopard’), but Irena is also inadvertently a stand-in for queerness. The desperation with which she throws herself into a heteronormative union, something she suggests she always thought would be denied her, is telling, and paired with her inability to consummate her marriage with her husband suggests Cat People could also be read as a lesbian parable. This is best exemplified by the ‘queerness’ of the cat woman who approaches Irena during her wedding celebration—it’s obvious to the normal majority there is something pronouncedly ‘off-putting’ about this woman on sight, enough to warrant immediate commentary and even derision. Meanwhile, Irena’s behavior warrants the intrusion of a psychiatrist, Dr. Judd (Tom Conway), hired to fix her intimacy issues (described as a man who ‘knows all there is to know about psychiatry’), at the behest of the ever intuitive Alice, a woman who breaks down to confess her love to Oliver during a watercooler conversation at work when the befuddled man confesses “I’ve never been unhappy before.” Which means, of course, he’s never been so confounded by anything so unnatural as marrying a woman who refuses to be sexual with him.

Jane Randolph, who gives off a certain Abbie Cornish vibe (and who is visually equated to the canary Irena accidentally kills), is the perfect American antidote, exemplifying all the light and airy feminine qualities the fiery and dark complected Simone Simon does not. The conversation she has with Conway about what love is really all about results in her conclusion “Nothing can change us. That’s what love is.” But something can certainly change Irena, as Alice is soon to find during the film’s signature moment of terror filmed exquisitely in the dark of a public pool.

DP Nicholas Musuraca (who would work with Tourneur on his signature film noir, Out of the Past, 1947) does wonders with the suggestive power of the shadows, which tend to dominate the film’s most notable sequences (such as another scene were Alice is pursued by Irena walking down the night time city streets). Opening with a quote from something titled Anatomy and Atavism, a reference to an evolutionary throwback, there’s something quite modern and chilling about the reference points of Cat People, which initially seems to be making remarkable use of urban decay in a WWII era metropolis, where strange things began to happen to women and men allowed anonymity in the city.

At every turn, the narrative suggests something innately American and normal about Oliver (Theresa Harris, an often uncredited black actress who starred alongside Barbara Stanwyck in Baby Face, gets a couple sequences as Minnie the waitress, always serving him his warm apple pie) while Irena is strange, elusive, and foreign (often she hides in the shadows of foliage, an exquisite visual touch). In his critical study on the director, Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall, Chris Fujiwara insightfully examines the visual personification of what’s going on with Irena, “in terms of dividing lines, barriers, traces, and absences.” This includes representations of gender and sexuality, human vs. animal, American vs. foreigner.

In the years since Tourneur’s Cat People, director Paul Schrader attempted a problematic remake on the fortieth anniversary in 1982, starring Nastassja Kinski and Malcolm McDowell. Much more sexualized (and with an awesome David Bowie track), Schrader attempts to flesh out the folklore of the cat people, to the detriment of the narrative. Tourneur is fast and loose with this efficiently paced seventy three minutes, edited by Mark Robson, who Val Lewton would hire to helm DeWitt Bodeen’s script for the equally moody The Seventh Victim (1943). The film has influenced other haunts, like Stephen King’s screenplay for the 1992 Mick Garris film Sleepwalkers, another scenarios where a strange race’s most insidious enemies are domestic felines, creatures which appear to be everywhere you look at any given time. As Tom Conway’s lascivious Dr. Judd deduces about the two different women in this film, one is afraid of the past while the other is afraid of the present—-suggesting, perhaps, the male of the species is afraid of the future, which is feminine, feline, or both.

Disc Review:

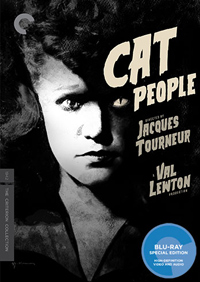

Criterion grants the classic title a new 2K digital restoration, presented in its original aspect ratio, 1.37:1 with uncompressed monaural soundtrack. Visuals and audio are superb in this magnificent transfer, especially for a film depending so much on shadowy cues and soundtrack effects (the snarling of felines, the blustery wind, or the sudden absence of high heels on pavement to indicate a transformation). Included is optional commentary from historian Gregory Mank recorded in 2005, with excerpts from an audio interview with Simone Simon.

Val Lewton – The Man in the Shadows:

Kent Jones directed this seventy-seven minute documentary on Val Lewton in 2008, narrated by Martin Scorsese.

Cine Regards:

An episode of the French television program “Cine Regards” is included here, featuring a 1977 interview with Tourneur at his home, where he discusses personal and professional influences.

John Bailey:

Criterion conducted this sixteen minute 2006 interview with cinematographer John Bailey (As Good As It Gets), who discusses how DP Nicolas Musuraca achieved the striking look of Cat People.

Final Thoughts:

An exciting genre addition to Criterion’s prolific catalogue, Cat People is rife with subversive subtexts, alarming suggestions, and potent performances. Cinema rarely manages something so creepy and bizarre as Tourneur and Lewton’s strangely poignant and unforgettable film.

Film Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.