Disc Reviews

Criterion Collection: Rosemary’s Baby | Blu-ray review

Just in time for Halloween, Criterion has remastered what’s long been culturally considered one of the most notable pieces of horror film making in cinematic history, the eerie classic, Rosemary’s Baby. Standing as not only the first adaptation of someone else’s material for auteur Roman Polanski, this would mark his first foray into Hollywood, and his final product still stands as template of the film industry’s far-reaching allure to achieve a European arthouse aesthetic successfully melded with mainstream pulp.

Just in time for Halloween, Criterion has remastered what’s long been culturally considered one of the most notable pieces of horror film making in cinematic history, the eerie classic, Rosemary’s Baby. Standing as not only the first adaptation of someone else’s material for auteur Roman Polanski, this would mark his first foray into Hollywood, and his final product still stands as template of the film industry’s far-reaching allure to achieve a European arthouse aesthetic successfully melded with mainstream pulp.

Still, to approach this classic title, (that’s become so deeply ingrained in our cultural syntax that nearly everyone knows what the titular baby is really synonymous with), as purely a genre exercise modulated simply to invoke fear and unease, would be a mistake. What makes the film transcend showy thrills is how it plunders into our more collectively subconscious fears, giving us a kitchen sink melodrama seared with paralyzing notions of Satanic cults and the antichrist, challenging deeply ingrained fears of religious brainwashing, and the forever assumed normalcy of the newly married heterosexual unit. While the film certainly isn’t as horrific or insidiously threatening as it was in 1968, Polanski’s masterpiece still strikes chords with us today, albeit for perhaps different reasons.

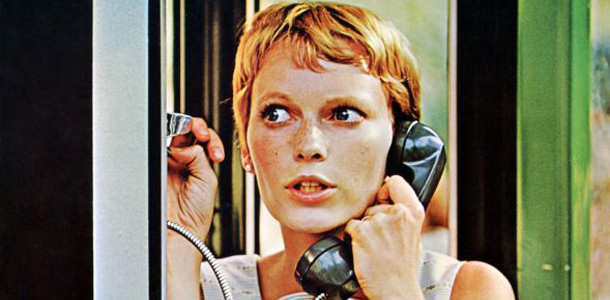

A young couple, Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and Guy Woodhouse (John Cassavetes) move into a huge New York apartment in a somewhat dilapidated yet prestigious complex, the Bramford. Both having migrated from less notable cities in the Midwest (Omaha, Baltimore), he’s a struggling actor, and she’s a very supportive housewife, happily prattling off Guy’s few notable credits, Luther and Nobody Loves an Albatross to anyone she converses with. Funny she’s keeps mentioning the second title, as she’s about to have an albatross of her own. Rosemary’s close personal friend, Hutch (Maurice Evans) warns the young couple of ‘Black’ Bramford’s notorious reputation as an apartment building with a haunted history of witches and devil worshiping denizens. The young couple laughs at the older man’s suspicious negations, and Rosemary strikes up a conversation in the laundry room with a woman she mistakes for an up-and-and coming actress named Victoria Vetri. The woman, Angela Dorian, or Terry to her friends, (actually played by actress Victoria Vetri), she explains that she had been scooped off the streets by Minnie (Ruth Gordon) and Roman Castavet (Sidney Blackmer), the old couple that reside in the adjoining apartment. Minutes later in the narrative, Terry is found splattered all over the sidewalk, apparently a suicide, bringing the Woodhouses and the Castavets into their respective orbits, thus setting into motion a paranoid housewife thriller involving rape and the dark one’s unclear insistence on begetting a child with a moral woman. Hell, Jesus had to come out that way too, no?

From author Ira Levin, to a majority of the cast members, to the general American audience at large (many of whom firmly believed the popular calculations that the antichrist was indeed born in 1966), there’s a palpable sensationalism about Rosemary’s Baby that held a different fascination with the generation it came out of. They were simply transfixed. It was a stroke of genius to have an agnostic, European director take the reins of material that could have been hysterically charged melodrama and condense it into an eerie exercise on isolation and madness, projecting it in front of us like a fearless man holding a snake by the head and asking us to peer closely into its eyes. From its opening moments, with character actor Elisha Cook Jr. showing the Woodhouses (wood houses are easy to burn) their ill fated future home, as a wordless, creepy lullaby plays over the placenta pink credit, to the final sequence of a doe eyed Farrow gleaming at her off screen progeny with the same kooky tune, Polanski, for an entire running time, hasn’t shown us one veritable supernatural moment. Our own hysterical beliefs and prejudices will either carry us away or examine the proceedings logically, and many of us even have our doubts long after the final reel. Ask some of your friends who’ve seen Rosemary’s Baby, whether recently or years ago, what they recall about the baby, and you’re sure to get varied responses. We definitely never get to see the devilish little lad, coined Adrian, but we get some unnerving details, like Rosemary screeching “What have you done to his eyes?” at her first glance. Well, he has his father’s demonic lamps, and John Cassavetes may have had thick eyebrows but his eyes looked pretty normal. More often than not, people want to recall that we saw something about the baby, but the brilliance is, Polanski has terrifyingly left it to our own far more wicked imaginations (something Ira Levin himself didn’t do).

What has to stand as the most agitating element of Rosemary’s Baby is our heroine’s betrayal by her very own husband, who sells his wife’s body to further his career, not unlike Faust sells his soul. On top of that, though she gives an iconic performance, there’s the incredibly weak portrayal of the vulnerable Rosemary by the waifish Mia Farrow. At the time, she had been married to Frank Sinatra and was currently a burgeoning television star on “Peyton Place.” Memorably, Sinatra had divorce papers served to Farrow while she was filming on set. He didn’t want a wife that worked (or outshined) him. The doubly betrayed Mia/Rosemary, a struggling female figure that has a desire and drive to break out on her own, could never be created in a remake of this material in today’s world. But she also creates a maddeningly weak figure of female passivity for today’s modern audiences. There’s a time, a place, and a cultural climate that was a perfect storm for the terror invoking possibility of Rosemary’s Baby that today exists as a superb example of master filmmaking from Roman Polanski. Between beautiful aerial shots of New York City, and a multitude of continuous takes, you can’t help but marvel at the artistry at work. There’s a continual sense of dread at things we don’t see, often happening directly out of frame, such as famous shot of Ruth Gordon on the telephone where audiences simultaneously craned their necks, yearning to see more. And that’s the greatest trick of all with Rosemary’s Baby, we will forever be, no matter how many times we see it, wanting more.

Disc Review:

Criterion beautifully gives Rosemary and company a newly restored digital transfer, and the result is ravishing. Cinema buffs and Polanski fans will much admire the title as a much deserved member of the prestigious collection. Even with Polanski’s highly accomplished filmography (leaving your feelings about his personal life at the theater door, if you’ve the maturity to do so) this is the cultural juggernaut for which he will be best remembered, a title that’s not only one of a handful of horror films nearly every movie goer is aware of, but one still highly regarded as simply one of the best films ever made. Criterion has amassed three notable extra features, including two feature length documentaries from 2012, one concerning the making of the film and the other concerning the abruptly shortened life of film’s composer. Also included is a 1997 radio interview with author Ira Levin.

Remembering Rosemary’s Baby

The best special feature on the disc, this series of 2012 interviews from Criterion plumbs the memories of producer Robert Evans, Mia Farrow, and Polanski. Evans relates how he maneuvered around producer William Castle, who had optioned the book and wanted to direct for himself. Castle, a sort of B-Hitchcock known for his schlocky, gimmicky cinema (he has a few examples of very fun, campy cinema, including a delightful axe-wielding Joan Crawford in 1964’s Straitjacket), does get to make a cameo appearance, but Evans made it clear he wanted Polanski from the start, and initially fooled the young European with a possible adaptation of Downhill Racer instead. Upon reading the novel, Polanski was immediately on board, and wanted Tuesday Weld for the role, poo-pooing Farrow, currently a television star (though she was the daughter of Hollywood royalty, director John Farrow and actress Maureen O’Sullivan). And Robert Redford was the first choice for Guy Woodhouse, but they eventually settled on John Cassavetes, himself already an established director, who financed his own productions with acting gigs. Cassavetes and Polanski had very different directorial styles, and by the end of the shoot, were not on friendly terms. A compelling interview from all three, with Evans in a white polyester shirt that makes him look like one of the coven members, this is a welcome extra for fans of the film.

Levin & Lopate

Ira Levin (who sadly passed in 2007), an esteemed author, playwright and even song writer, wrote several novels, three of which have been adapted into some of the best genre efforts to come out of the 60s/70s (besides this title, he wrote The Boys From Brazil and The Stepford Wives). He also wrote one of the longest running plays, Deathtrap, which was adapted into a 1982 film by Sidney Lumet starring Michael Caine and Christopher Reeve, which contained a plot twist so culturally combustible, it killed the box office potential for the film. But in 1997 he published a long gestating sequel to his most famous work, Son of Rosemary, set thirty years later, in which Rosemary, allowed to raise her son for the first six years of his life, is put into a coma by the coven and awakens suddenly at the end of the millennium to see her son revered as a Messiah type figure. For those who have read the novel, you’ll find that Levin resorts to a ridiculous flourish at the end (which he refers to as an “ironic edge” in this interview), but though this interview focuses on this lesser text (in which Levin seems confident of a movie deal that never transpired, discussing his wishes for Farrow’s return and Brad Pitt as the petulant Adrian—what lofty pipedreams) what’s notable is Levin’s guilt trip over Rosemary’s Baby. Though he considers Polanski’s adaptation one of the most faithful perhaps ever committed to film, as a non-believer, he felt that audiences would have seen the ridiculousness of his narrative instead of championing it as a testament to the existence of satan, and, therefore, god. He firmly believes that, if not for his book, there would be far fewer fundamentalists today. He certainly had a healthy view on his cultural influence.

Komeda, Komeda

This feature length documentary explores the life of composer Krzysztof Komeda, a jazz musician who scored this film as well as Polanski’s short film Two Men and a Wardrobe (1958), Knife in the Water (1962) and Cul-de-Sac (1966). Polanski speaks at great length about the composer, as well as Polish auteur Andrzej Wajda, who had Komeda score his 1960 film Innocent Sorcerers (in which Polanski had an acting role). Komeda died mysteriously in 1969 after head injuries inflicted in a possible fight. Featuring interviews with many of his colleagues and his sister, the documentary, while not innately about Rosemary’s Baby, is an intriguing addition.

Final Thoughts:

The secret weapon of Rosemary’s Baby has to be the delightful Ruth Gordon as the loquaciously intrusive Minnie Castavet, for which she deservedly won a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award. (Sadly, she would reprise her role in an ill received 1976 television sequel, Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby). Interestingly, the film serves as the middle in a trilogy of Polanski’s films that explore madness in the artificial isolation of apartment complex living (the other two deliriously good films are Repulsion, 1965, and The Tenant, 1976). Those looking for spine-tingling thrills may be disappointed by our lofty 2012 standards, but there’s undeniable craftsmanship at work here, a slow burn chiller that isn’t without timeless creepy moments, like the music springing up as Rosemary rises her hands to her face in horror, or when she realizes during the rape scene that she may not be dreaming. Farrow cites Sidney Blackmer’s discomfort with chanting “Hail Satan!” in the film’s final sequence, but some forty odd years later more and more people in the enlightened world are discovering that we should be discomforted at any moniker injected after “Hail.” Turn the lights off, get some friends together, and whether revisiting or uninitiated, watch Rosemary’s Baby. All squabbles aside, you have to admit that Rosemary Woodhouse has the best devilled eggs. And don’t you dare ask for the recipe.