Reviews

A Married Woman (1964) | Review

Charlotte’s Web: Godard’s Detailed Fragments of Woman Consumed

Cohen Media Group presents a limited theatrical re-release of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 film A Married Woman in a new 2k restoration, one of the auteur’s more comprehensible items during his most prolific, and iconic experimental efforts in the glory days of the Nouvelle Vague. The extended intertitle asserts it to be “fragments of a film shot in 1964—in black and white,” which provides an early indication of the isolated moments sewn together to relay the predicament of a young woman who discovers she’s pregnant, but has no idea if the child was sired by her lusty lover or her paternal husband (and clearly, the complex subtexts presented reach beyond notions of black and white). Adrift in her own materialistic fantasies, she’s forced to abandon her consumer tendencies to contend with her uneasy predicament, torn between their needs and the affections of her young step-son.

Cohen Media Group presents a limited theatrical re-release of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1964 film A Married Woman in a new 2k restoration, one of the auteur’s more comprehensible items during his most prolific, and iconic experimental efforts in the glory days of the Nouvelle Vague. The extended intertitle asserts it to be “fragments of a film shot in 1964—in black and white,” which provides an early indication of the isolated moments sewn together to relay the predicament of a young woman who discovers she’s pregnant, but has no idea if the child was sired by her lusty lover or her paternal husband (and clearly, the complex subtexts presented reach beyond notions of black and white). Adrift in her own materialistic fantasies, she’s forced to abandon her consumer tendencies to contend with her uneasy predicament, torn between their needs and the affections of her young step-son.

Charlotte (Macha Meril) spends her mornings in the illicit embrace of her lover, Robert (Bernard Noel), an experienced journalist. Her husband Pierre (Philippe Leroy), a pilot, is due to return from an extended trip, but she doesn’t seem very enthused when she greets him with his son Nicolas (Christophe Bourseiller), a child from his first marriage. Emotionally immature, she drifts haphazardly between them, even though both men seem rather invested in continued interactions with her. But Charlotte seems more enthused about shopping and comparing herself to other women, as everything around her indicates she must do. When she discovers she’s pregnant, Charlotte is unsure of her next move since she’s not sure if her feelings for either man are what one would call love.

Using newspaper clippings and a barrage of various bits of advertising to provide glib commentary on Charlotte’s emotional estrangement from herself and others, A Married Woman reveals itself to be a rather terse but effective study on consumerism and gendered commodification. It would be Godard’s seventh feature since his 1960 debut Breathless, and would arrive in the theaters just a few months after the more iconic Band of Outsiders (not to mention two other short segments he would helm in 1964 alone). Curiously, there’s no sign of then wife Anna Karina, who headlined most of Godard’s 60s titles until their separation following 1965’s Made in U.S.A. Instead, it features a rather cool performance from Macha Meril (who would appear in Bunuel’s Belle de Jour and Argento’s Deep Red) as Charlotte, a woman dissected by Raoul Coutard’s pronounced framing while snippets of Beethoven tune in and out with Godard’s usual manipulations of soundtrack.

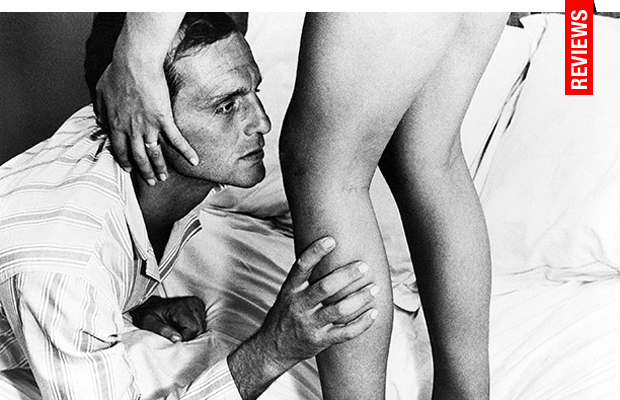

We hear her voice off-screen while her left hand (and the wedding band announcing ownership) appears on a white bedspread. A man’s hand, her lover’s, grips her forearm aggressively, exerting his own claim to her flesh. And thus the camera introduces us to Charlotte part by part as we admire her shoulder blades, her midriff, and finally her coiffed bob. She professes to love this Robert, but he rebuffs the notion as a faulty idea, stating love is “a house you can never enter” because one can never really be ‘inside’ another. And thus, Godard makes a solemn film about surfaces, and we watch Charlotte as she measure her breasts to see if they’re the perfect size (as outlined in a magazine), listens to two young women discuss the process of heteronormative sexual initiation, and coolly admonish a suitor for an off-screen indiscretion, “there was no need to rape me and slap me around.”

In essence, Charlotte’s emotional alienation makes her seem an awful lot like the capitalistic precursor to a Stepford Wife, depending solely on how the men in her life define love, advertising stating ‘here’s what every woman needs to know,’ or in her doctor’s case, explaining the appropriateness of pleasure. Meanwhile, neither of her lovers can rightly read her emotional state. “Are you sulking?” her husband asks in an early reunion. Later, her gentleman caller asks if she’s crying (rather than why), despite noting tears in her eyes. Tellingly, she knows nothing about the world outside of her bubble, as evidenced when she’s led into a conversation concerning Auschwitz, since war criminals were currently on trial in Berlin, but she thinks the infamous death camp is a reference to Thalidomide. She receives vague lessons regarding famed German artists, snapshots of Beethoven and Marlene Dietrich flash before our eyes, though Charlotte seems to care little for them. At one point she hums Pete Seeger’s “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” which was famously covered by Dietrich, an exceptional anti-war hymn which asserts young women will always foolishly run into the arms of young men, who in turn foolishly run to their deaths in war, a never-ending cycle of naivety passed from one generation to the next.

Towards the end of A Married Woman, a question is posed—“How far can a woman go in love?” Since Charlotte’s interactions are suggested to be mere superficial stimulations, Godard’s implications are quite subversive since women are left ill-equipped, even with language they speak, to define (or admit) how they feel, thus forced into being tethered to men in unions doomed to imitate romantic conceits.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.