Reviews

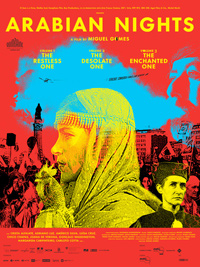

Arabian Nights Trilogy | Review

Tales of a Tale of Tales: Gomes’s Three-Part Epic Is A Monument To The Plight Of Portugal’s Working Class

There may be more traditionally successful films released in 2015, but there won’t be any as monolithic, impassioned, euphoric, mad, or aesthetically and socially important as Arabian Nights. For the three-volume, 383-minute ode to the people struggling through Portugal’s current economic crisis, Miguel Gomes appropriates the mythological and formal conceits of the centuries-old collection of Arabic folk tales of the same name, in which Scheherazade spends a thousand and one nights distracting her new husband, the Persian king Shahryar, with alluring stories so that he will not kill her. Rather than using any of the actual tales included in the collection, Gomes spent a year (Summer 2013 to Summer 2014) making up eight of his own, each with its own distinct tone, visual style, characters, degree of collaboration with locals, and reliance on improvisation. The result–which is mostly hit, a bit miss, always fresh–is a work so staggering, bold, and sui generis that it appears destined to be instantly canonized among the great works of 21st century cinema.

There may be more traditionally successful films released in 2015, but there won’t be any as monolithic, impassioned, euphoric, mad, or aesthetically and socially important as Arabian Nights. For the three-volume, 383-minute ode to the people struggling through Portugal’s current economic crisis, Miguel Gomes appropriates the mythological and formal conceits of the centuries-old collection of Arabic folk tales of the same name, in which Scheherazade spends a thousand and one nights distracting her new husband, the Persian king Shahryar, with alluring stories so that he will not kill her. Rather than using any of the actual tales included in the collection, Gomes spent a year (Summer 2013 to Summer 2014) making up eight of his own, each with its own distinct tone, visual style, characters, degree of collaboration with locals, and reliance on improvisation. The result–which is mostly hit, a bit miss, always fresh–is a work so staggering, bold, and sui generis that it appears destined to be instantly canonized among the great works of 21st century cinema.

While the film’s three volumes can function in isolation from one another due to the lack of narrative continuity from one tale to the next, they should all be ingested with as narrow a gap as possible between viewings to maximize its impact. This is a film designed to exhaust and overwhelm, and its sea of streams of stories can only express the sprawling, democratic nature in which it was constructed if processed as a totality, which is so much more than the sum of its parts.

Volume 1, The Restless One is comprised of three tales preceded by a prologue that primarily functions as a mission statement for the entire project. Ruminating on the loss of jobs in the shipyards in Viana do Castelo and a plague of wasps that have terrorized the region’s beehives, this first section takes us back to the grainy, cinema verité vibes of Gomes’s Our Beloved Month of August (2008). Gomes appears here, playing himself, expressing doubts about the entire endeavor, fleeing the set and thus prompting his production crew to chase after him. “What is the Law for Cinema and Audiovisual Media?” he ponders. Cut to fiction.

The three, medium-feature-length stories that follow range from the satirical to straight documentary ethno-portraiture. “The Men with a Hard-on” mockingly sketches a crew of members of the International Monetary Fund who, during negotiations over austerity measures with the Troika (i.e., the motivating impulse for this entire film), learn of a cream that gives them days-long erections (their crooked actions have annihilated their abilities to get it up). “The Story of the Cockerel and the Fire” sees a cockerel on trial for his too-early morning crow, which generates enough goodwill with locals that he fares well in a municipal election, where “The Swim of the Magnificents” showcases three working class bathers who participate in an annual New Year’s Day plunge into the frigid Atlantic. The tales are decorated with playful stylistic flourishes, such as an onscreen countdown to a fireworks display, signaling Gomes’s refreshing belief that the greed, corruption, and selfishness that’s led to his country’s present state need not be mimicked with aesthetic austerity.

The second and overall most successful volume, The Desolate One, leads off with the tale of a fugitive, “Chronicle of the Escape of Simão ‘Without Bowels’,” who remains skinny despite his gluttony, participates in ass-slapping orgies in open fields, and generally just attempts to survive despite his removal from society and civilization. “The Tears of the Judge” is an archaeological gaze into the justice system, revealing the impossibility of coming to a clear-cut understanding of a single criminal act, and then the two-part “The Owners of Dixie” recalls Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), offering a spry yet ultimately devastating account of the quirks of a residential tower community as a dog transitions from one owner to the next.

The third and final volume, “The Enchanted One,” represents both the summit of Arabian Nights‘s heights and something of an anti-climax. Beginning with something of a rewind, the first forty minutes returns the focus to Scheherazade herself, and features some of the most vivid, hypnotic, and (yes) enchanting filmmaking of Gomes’s career. Verging on being a musical, this section features a soundtrack that leaps through pop hits, a tabla accompaniment for a khattak dance that fades into a glorious superimposition/composite, footage of a surreal kite festival and a turtle race are sliced in from nowhere, and details of a fling with the vapid, but remarkably fertile, Paddleman (Carloto Cotta)–all combining to achieve a delirious bliss.

When this extended intro/interlude ends, we cut in the seventh, and by far longest, tale, “The Inebriating Chorus of the Chaffinches.” Here, Gomes studies a group of men, including Simão (Chico Chapas) from Volume 2, who are training their birds to compete in a singing contest. The men utilize the best audio analyzation/manipulation software they can acquire to compose pieces for the birds, which can get so exhausted during a performance that they often drop dead on the spot. Gomes allegedly contemplated making this tale its own standalone film (it’s certainly long enough to be one), and it seems like it might have worked better that way, without the pressure of closing out such a gigantic opus. Spliced into the center of this tale as a kind of respite or intermission is the brief “Hot Forest” tale; barely ten minutes long, this one features footage of a protest with voiceover from a Chinese student (her name translates to ‘hot forest’) describing her experience in Portugal.

Schizophrenic and bloated, it shouldn’t be a surprise that not every moment of this works. But it’s a tribute to Gomes’s democratic and impulsive methodology that the films remains vibrant, alive, and always unpredictable, to say nothing of its incredibly generous spirit. This is cinema that tries to change the world, and strives to evolve the ways in which cinema can be made and watched. Indulgent as it (necessarily) is, there is not an objectionable bone in its body, and one can only hope that films of its caliber become a regular fixture in the coming decades’ cinema landscape.

Reviewed on May 20th at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival – Director’s Fortnight – 383 mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Blake Williams is an avant-garde filmmaker born in Houston, currently living and working in Toronto. He recently entered the PhD program at University of Toronto's Cinema Studies Institute, and has screened his video work at TIFF (2011 & '12), Tribeca (2013), Images Festival (2012), Jihlava (2012), and the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley. Blake has contributed to IONCINEMA.com's coverage for film festivals such as Cannes, TIFF, and Hot Docs. Top Films From Contemporary Film Auteurs: Almodóvar (Talk to Her), Coen Bros. (Fargo), Dardennes (Rosetta), Haneke (Code Unknown), Hsiao-Hsien (Flight of the Red Balloon), Kar-wai (Happy Together), Kiarostami (Where is the Friend's Home?), Lynch (INLAND EMPIRE), Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs), Van Sant (Last Days), Von Trier (The Idiots)