Reviews

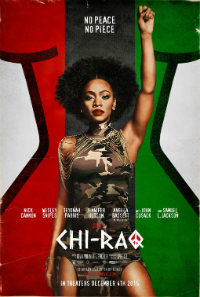

Chi-raq | Review

Sexual Healing: Spike Lee’s New Joint Aims to Anoint

Provocateur Spike Lee continues to fling his ambition into surprising experimental formats and narratives. Following the box office failure of his 2008 war drama Miracle at St. Anna, Lee has branched out inventively, though his feature narrative products have not often received the same level of critical acclaim elicited by his early titles from the late 80s and early 90s when he was a lone representative of black independent cinema at the art house. After funding 2012’s Red Hook Summer out of pocket and controversially trawling Kickstarter for 2014’s Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (a remake of Bill Gunn’s 1973 classic Ganja & Hess), he’s back with his grandest platform in quite some time with Chi-raq, so named for the controversial moniker Chicago has earned due to the astronomical urban violence plaguing the metropolis’ South Side. Assembling an impressive cast, including a number of Lee’s most notable collaborators from his past filmography, he takes a heady contemporary social issue and transposes it onto the classic Greek play Lysistrata, written by Aristophanes in 411 B.C. Though the resulting farce is sometimes a mixed bag, Lee’s lost none of his creative flair. While racially motivated violence continues to hang like a constant, grisly sneer on the face of subjective modern media sources, Lee’s ambitious presentation may feel too trite or too heady for audiences preferring to see these issues doused in buckets of blood. But for every slight misstep, the film is an unexpectedly impressive recalibrated allegory.

Provocateur Spike Lee continues to fling his ambition into surprising experimental formats and narratives. Following the box office failure of his 2008 war drama Miracle at St. Anna, Lee has branched out inventively, though his feature narrative products have not often received the same level of critical acclaim elicited by his early titles from the late 80s and early 90s when he was a lone representative of black independent cinema at the art house. After funding 2012’s Red Hook Summer out of pocket and controversially trawling Kickstarter for 2014’s Da Sweet Blood of Jesus (a remake of Bill Gunn’s 1973 classic Ganja & Hess), he’s back with his grandest platform in quite some time with Chi-raq, so named for the controversial moniker Chicago has earned due to the astronomical urban violence plaguing the metropolis’ South Side. Assembling an impressive cast, including a number of Lee’s most notable collaborators from his past filmography, he takes a heady contemporary social issue and transposes it onto the classic Greek play Lysistrata, written by Aristophanes in 411 B.C. Though the resulting farce is sometimes a mixed bag, Lee’s lost none of his creative flair. While racially motivated violence continues to hang like a constant, grisly sneer on the face of subjective modern media sources, Lee’s ambitious presentation may feel too trite or too heady for audiences preferring to see these issues doused in buckets of blood. But for every slight misstep, the film is an unexpectedly impressive recalibrated allegory.

Lysistrata (Teyonah Parris) is in love with aspiring rapper Demetrius Dupree (Nick Cannon), otherwise known as Chi-raq, sharing his stage name with the newly coined nickname for the windy city, a mish-mash of Chicago and Iraq. Dupree’s gang, the Spartans, are at war with the Trojans, headed by Cyclops (Wesley Snipes). With stray bullets killing innocent black children every day, Lysistrata is motivated to put a stop to the violence after witnessing a mother (Jennifer Hudson) come home to find the body of her dead child in the street. Rallying together the girlfriends of both rival gang members, they decree their men will be denied intercourse until peace can be achieved.

Chi-raq’s sing-songy playfulness feels like a spoken word rendition, complete with a cadre of timely references already dating the material (such as evoking directly the names of recently killed black youths, like Trayvon Martin, while other mentions, such as a Deliverance joke, seem a bit too tired for an otherwise exuberant exercise). It feels a bit like Carmen: A Hip Hopera (2001) meets Lee’s Malcolm X (1993), though its warring groups also recall his early title School Daze (1988). But the film also descends into a sort of loopiness akin to She Hate Me (2004), one of Lee’s less acclaimed experiments. A highly notable cast mostly meets expectations, with Angela Bassett as an outspoken activist and Samuel Jackson as narrator Dolmedes popping up continuously. It’s refreshing to see Nick Cannon cast against type as a ruthless gangster, but he’s also distracting (not unlike qualms about Janet Jackson in John Singleton’s Poetic Justice, 1993). More refreshing is newcomer Teyonah Parris (Dear White People, 2014) as Lysistrata, who makes even the more clunky bits of sexual dialogue seem palatable. With a little luck, leading a Spike Lee joint will serve her career better than it did Anthony Mackie.

Lee seems fascinated by the pulpit (as evidenced by Red Hook Summer), and gives John Cusack an outstanding, thunderous monologue at the funeral of Jennifer Hudson’s child. It’s an important bit of casting, a reflection of the interest and vocal support needed by everyone in any given community affected by violence or despair. On the weaker end, however, Hudson seems emotionally listless in a role calling for the exact opposite—and yet, her presence here adds an additional textual resonance since her mother and two other family members were murdered in Chicago in 2008. Likewise, Lee makes excellent use of Wesley Snipes as rival gang leader Cyclops, a role which feels like a continuation from one of Snipes’ early signature roles, New Jack City (1991). We can assume Harry Lennix approves of Lee’s social issues depicted here (following his aggressive castigation of Lee Daniels’ The Butler as pandering in 2013), while D.B. Sweeney is another blight as the Mayor, a kind of insensitive authority figure modeled like Michael Rapaport in Lee’s Bamboozled (2000). It’s an exciting mixture of juxtaposing elements further enhanced by the textual allusions peppered throughout by Lee and co-screenwriter Kevin Willmott.

Not all of Aristophanes’ original text seems to translate, as Lysistrata makes war and its corresponding cure a purely heterosexual dilemma. Lee adds a few funny nudges about men on the down low and a cameo lesbian character but abstains from using homosexuality as a crutch for laughs. Similar in perspective to the dystopic The Lobster (2015), queer characters remain a great invisibility in the realm of allegory from heterosexual filmmakers. And though its narrative happenings become a bit murky in the second half (such as why the unarmed women can’t be removed from the armory, etc.), Chi-raq is also one of Lee’s more visually impressive ventures in years, capturing a Chicago lensed by Matthew Libatique (Requiem for a Dream, 2000) and borrowing Ryan Coogler’s tactic of incorporating social media splashed across the screen. The soundtrack is equally impressive, and even if Nick Cannon’s title track may seem a bit too pointed, a winning combination of new items from Jennifer Hudson, Sam Drew and even R Kelly adds to the films’ catchy flavor. Lee directed corresponding music videos for several of the tracks, including “WGDB” by Kevon Carter and Cannon’s “Pray 4 My City.”

For all of Lee’s harangues on the ‘cinema’ of Tyler Perry, Chi-raq quite often feels akin to an emotionally exaggerated rollercoaster depicted in a Madea adventure (a character ironically sharing a phonetically name with another tragic Greek character), with sexual innuendo, musical asides, goofy humor and abject despair often unspooling back to back. But Lee’s timely exercise manages to be something much more important and incredibly relevant as concerns the continuation of urban violence, aka black on black crime.

In its most lucid moments, Chi-raq depicts a predicament borne out of historical socioeconomic ills continually packaged as a race issue. This is not an anti-white or even anti-establishment film, but a lesson in the power of ownership and individual responsibility as concerns sanctioned behaviors. Powerfully, Lee’s allegory evokes hope in that the power of peace is a possibility residing in each and every one of us. Increased rhetoric concerning an ‘us vs. them’ mentality, whether it be law enforcement vs. civilians or whites vs. everyone else, continues socially defined differences rather than uniting us in our similarities. Lee’s gracious message seems to be ahead of a present climate of blame even as it’s wrapped in the wardrobe of an ancient culture – at the end of the day, don’t all lives matter?

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.