Detroit | Review

Horror Hotel: Bigelow and Boal Recount Grim Chapter of Racial Disparity

This year’s most harrowing horror movie, Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, happens to be based on events which took place nearly fifty years prior to the exact date its reenactment reaches theaters. Set during the Detroit riots of 1967, Bigelow and her usual scribe Mark Boal (who penned the Oscar winning The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty), focus intensely on the behind-the-scenes violence which resulted in the murder of three black men in a hotel which happened on the third night of the riots.

This year’s most harrowing horror movie, Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, happens to be based on events which took place nearly fifty years prior to the exact date its reenactment reaches theaters. Set during the Detroit riots of 1967, Bigelow and her usual scribe Mark Boal (who penned the Oscar winning The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty), focus intensely on the behind-the-scenes violence which resulted in the murder of three black men in a hotel which happened on the third night of the riots.

Staged as a gritty docudrama which takes a no holds barred approach in depicting the sadistic racism which defined the Detroit Police Department and resulted in a harrowing night of abuse and atrocity, Bigelow’s searing portrayal of bigotry and brutality may have jumped a century past the depictions of slavery which still prevail perennially on the awards circuit in the US, but lacks a certain sense of complexity beyond its obvious relation to contemporary American issues. As it stands, this may be Bigelow’s most notable effort to date, but isn’t as finely wrought as one might expect.

On July 25, 1967, up-and-coming singer Larry Reed (Algee Smith) and his mild mannered friend Fred (Jacob Lattimore) take refuge in the last available room at the Algiers Hotel, a good time joint where illegal activities define the venue’s ribald entertainment value. Sulking after his all-male band is thwarted from singing at a popular downtown theater when the rioting outside shuts down the street, Larry begins to schmooze the two young white women (Hannah Murray, Kaitlyn Dever) holed up in the hotel. The girls introduce them to their friends, including wild card Carl (Jason Mitchell), who foolishly shoots a toy gun out the window, leading the already irate police force to raid the hotel in search of a sniper, meanwhile throwing a tumultuous group of civilians into a long night of hell.

Opening with expressive credits (similar in feel to the folklore cartoons of M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water) which provide a history lesson on the migration of blacks seeking job opportunities in the north (lightly skipping over the terror and tribulation which marked decades of history for blacks in America since their ancestors were stolen) leading up to the riots which marked Newark and then Detroit. The accomplishment of Detroit is how it sets up a veritable “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” dichotomy for white vs. black experience in the United States. “It’s Time We Knew,” boldly declares the film’s tagline.

Fifty years down the road, with continual news of black people murdered by white police officers across the country, such a sentiment seems patronizing, and lends an aura of exploitation to the nobility of Boal and Bigelow’s rendering of one bullshit night in suck city. If white America couldn’t understand why black Americans chose to defend O.J. Simpson despite overwhelming evidence pointing to the role he most likely played in the murder of his ex-wife, perhaps an item like Detroit could be a learning tool for them—or perhaps those who feel racism is/was no longer an issue after Barack Obama’s two terms as President of the United States. Perhaps it’s time for those people to know. But for anyone who hasn’t been living under a rock or willfully ignorant of white privilege, Detroit feels like a hazing experience topped off with a patronizing wallop of courtroom procedural. And this is where Bigelow and Boal fail—they don’t connect the dots between the extremists and the ignorant shield white privilege affords. When one battered and bruised victim barely escapes the Algiers, he runs into a white police officer. Cowering and bleeding, the officer valiantly offers his arm, exclaiming, “Who could do this to a person?” And, so Boal and Bigelow ask the audience point blank—and therefore assuage any possibility of complicity to white audience members by driving home the message of bad apples versus regular Joes—good whites do exist, bless ‘em, they just had no idea such atrocious things can and do happen to black Americans.

Despite its preconceptions, Detroit is a powerful, visceral provocation. The first two thirds, which are set in the sweaty, nightmarish hotel and consist mainly of endless, inescapable degradation of innocent black men (and two white women) at the hands of violent, white bigots, are formidably potent in their ability to upset. The seething rage and hatred which can easily be projected upon Will Poulter’s ringleader (hewn from the same crassly racist cloth as Bryce Dallas Howard in The Help, 2011), and his equally incompetent posse, including Ben O’Toole and Jack Reynor, is dispelled with an ungainly finale in an unnecessary courtroom sequence where justice, of course, is not duly served.

End credits reveal only how little has changed five decades later regarding the accountability of law enforcement, and perhaps this is the rueful power/intention of Detroit. And yet, there’s little by way of finesse to tease out or even suggest how pervasive institutionalized racism has become, and what factors, beyond the obvious, led up to this particularly grueling formulation of perverted authority.

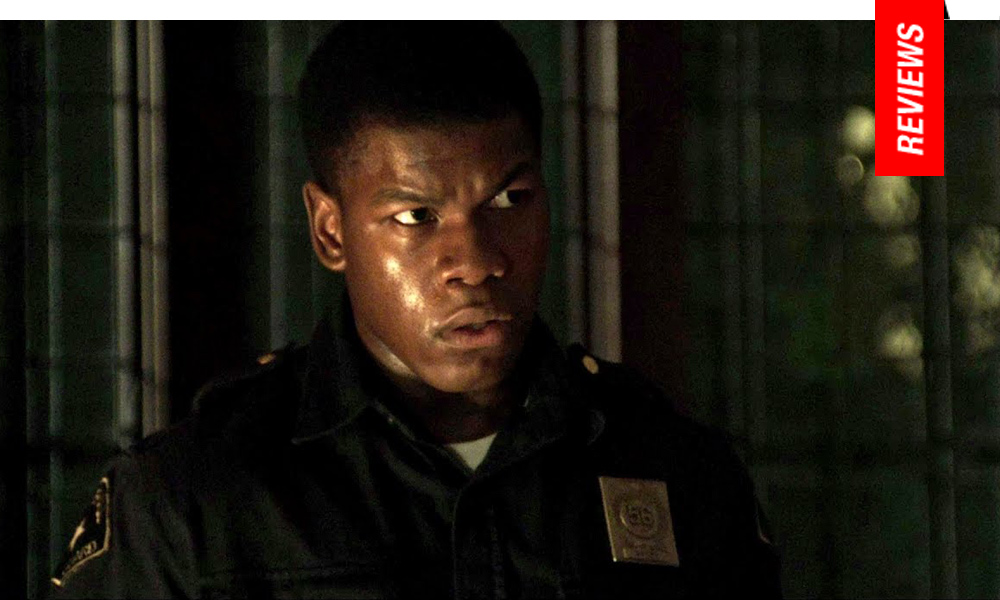

While Bigelow and DP Barry Ackroyd customize this experience with an extra wallop of anxious camera moves, ratcheting up the tension unbearably as the camera intensely and abruptly scatters over the unfortunate hotel victims, theirs is a sometimes compromised achievement. A sprawling cast of notable faces consists of mainly sympathetic performances, particularly from John Boyega, Anthony Mackie, Jacob Lattimore, and Algee Smith who stands out as the film’s searing flag of victimhood. But at the end of the day, Detroit plays like a first-wave artifact, a study in American Racism 101. It may outline where we’ve been, but implies nothing about where we’re going, refusing to acknowledge the underlying issues which have been merely subverted into less easily defined form.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.