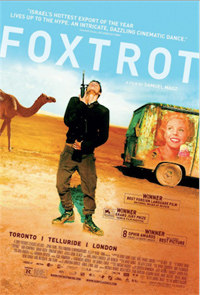

Foxtrot | Review

Dancing in Hollow: Maoz Moves Sharply between Shock, Grief & Absurdity

Israeli director Samuel Maoz was one of the most surprising Golden Lion winners in recent years, having walked out of Venice in 2009 with the top prize for his feature debut Lebanon. A tough, intense watch spent entirely in the company of an Israeli tank crew during the 1982 Lebanon War (in which Maoz himself served at the age of 20), the film was bluntly powerful and brought Maoz some deserved recognition. Almost a decade later, the director returns with a much more complex and layered three-part drama that nonetheless retains the urgency and authenticity of Maoz’s desire to engage with his own experience of war.

Israeli director Samuel Maoz was one of the most surprising Golden Lion winners in recent years, having walked out of Venice in 2009 with the top prize for his feature debut Lebanon. A tough, intense watch spent entirely in the company of an Israeli tank crew during the 1982 Lebanon War (in which Maoz himself served at the age of 20), the film was bluntly powerful and brought Maoz some deserved recognition. Almost a decade later, the director returns with a much more complex and layered three-part drama that nonetheless retains the urgency and authenticity of Maoz’s desire to engage with his own experience of war.

Foxtrot opens on a classic setup: army representatives at the doorstep, a bell ringing, and a mother instantly and painfully realizing what news they bring. Except the tone and pacing of the whole thing feel different, simultaneously colder, heightened and more acutely performative. With Dafna immediately knocked out by the news of the death of her son, the first part of the story centers around husband Michael, who sees his own apartment taken over by disturbingly efficient soldiers with the right answer to any question, even the ones Michael has no intention of asking. It’s the tidiest and most controlled of personal invasions, designed to contain and overwhelm while ostensibly offering practical help. Michael’s true devastating grief takes a while to surface, but Maoz is already planting the seeds of a more surrealist take on the story, which will become apparent in the abrupt cut to the second segment.

Maoz has always been technically solid, though Lebanon could only offer a limited canvas for his camera and space direction. Here he shows tight, precise control on the proceedings, for instance through disorienting and wobbly overhead shots of Michael, framed as if he were drowning into the tiled floor of the apartment. The most memorable is however a sort of semi- circular shot around Michael, performed twice and only truly completed a third time later in the film. It amplifies the disconnect between the soldiers (and, at that point, his own family members) and him, while the shift in perspective seems an attempt to redefine the masculine role of the Israeli family man that can never be completed. Until, that is, Foxtrot has become a cross-generational study of institutionally-mandated trauma.

It takes a while to get there, and you wouldn’t necessarily predict a spectacular dance scene at a border checkpoint or a camel wandering around by itself to be part of the journey. And yet that’s where the movie shines – playing on a certain expectation of single-mindedness and narrow focus, with the family as the equivalent of the Lebanon tank crew (which they are, in a way, but it’s only in retrospect that you see the battle they’re fighting this time), only to snatch the cause of their grief away, take a step back, and continue the foxtrot. The thing about the foxtrot, though, is that you end up right where you started.

The third act is the least flashy, but it’s the one that makes sense of all the others, operating as a synthesis, an explanation, and a bittersweet return to reality for Michael, Dafna and their daughter. Maoz is done aestheticizing grief by bursting into the frame with his camera, like he did in the beginning, and he has also forever sunk in a hail of machine-gun fire the pictorial surrealism of the middle section. Now it’s down to each character to negotiate acceptance, love and sorrow at the family table.

Once you come around to fully appreciating the long game Maoz was playing, it’s clear this is a remarkably accomplished piece of drama, echoing the work of Maoz’s compatriot Ari Folman in Waltz with Bashir. Folman took part in the same war, but the symbolic imagery he chose for Bashir (released just one year before Lebanon) made us think the two filmmakers stood at opposite ends of the spectrum in artistically coming to terms with such horror. Now we know that Maoz just needed to make a stop by that tank, claustrophobically grounded in reality, before attempting to build something else – something more evocative – on top of it.

Reviewed on September 10th at the 2017 Venice Film Festival – Competition. 114 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

A freelance film critic and programmer, Tommaso Tocci is based between Paris and Rome. He covers the European festival circuit and he's a member of FIPRESCI and the International Cinephile Society. His Top 3 for 2021: After Blue (Bertrand Mandico), Titane (Julia Ducournau), What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? (Alexandre Koberidze).