Reviews

Leviathan | Review

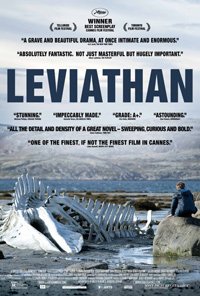

On the Waterfront: Zvyagintsev’s Sprawling Opus of a Modern, Devouring Regime

Back with his fourth feature, Leviathan, Russian auteur Andrey Zvyagintsev succeeds in cinematic sublimity with this multilayered and operatic exploration of the crushing corruption of an unchecked regime. While each of his films have taken home prestigious awards (The Return won the Golden Lion at Venice in 2003, The Banishment snagged Best Actor at Cannes in 2007 while 2011’s Elena roped the Special Jury Prize for Un Certain Regard), this latest feature should solidify his unparalleled ascension as the most important auteur to rise out of Russia since Andrey Tarkovsky. Time may prove his to be the more potent title, a damning examination of the turpitude bred by an archaic and untoward establishment.

Back with his fourth feature, Leviathan, Russian auteur Andrey Zvyagintsev succeeds in cinematic sublimity with this multilayered and operatic exploration of the crushing corruption of an unchecked regime. While each of his films have taken home prestigious awards (The Return won the Golden Lion at Venice in 2003, The Banishment snagged Best Actor at Cannes in 2007 while 2011’s Elena roped the Special Jury Prize for Un Certain Regard), this latest feature should solidify his unparalleled ascension as the most important auteur to rise out of Russia since Andrey Tarkovsky. Time may prove his to be the more potent title, a damning examination of the turpitude bred by an archaic and untoward establishment.

Living in the home that he’s built with his own hands on the waterfront of the Barents Sea, Kolya (Alexei Serebryakov), has recently been notified that the Vadim (Roman Madyanov), mayor of the nearby town, will be forcing him to sell his land, and at a disgustingly reduced rate for what the property is actually worth. A mechanic and father of a teenage son, Kolya is married to his much younger second wife, Lilya (Elena Lyadova), who doesn’t seem to think moving is such a bad idea. But Kolya has contacted his old army buddy turned lawyer, Dimitri (Vladimir Vdovitchenkov) for help. Arriving from Moscow with a boatload of damning information on the crooked mayor, Dimitri attempts to end the forced sale of Kolya’s land by threatening Vadim with exposing him. But blackmail only seems to inflame already roiled tempers.

The multiple definitions of its title lend the film a poetic motif. The rotting husks of giant ships floating idly offshore and the skeleton of a long dead marooned whale littering the beach are parallels for the final image of the Orthodox church that supplants itself atop Kolya’s home—each are hollowed out vestiges of entities that were once endowed with hope, life, and purpose. The haunting whale carcass recalls the post-apocalyptic world of Marco Ferreri’s The Seed of Man (1969), in which a desolate couple contends with the possibility of procreation, the bones of the beast like a washed out specter urging otherwise.

Zvyagintsev reunites with his Elena star Elena Lyadova, here granting her a more prominent role as a woman who causes the unraveling of her husband and his best friend. This is the internal turmoil in their stance against the swarthy mayor which anticipates the eventual defeat of their cause. As the lawyer Dmitri, actor Vladimir Vdovitchenkov (who US audiences may recognize from Fernando Mereilles’ 2011 film, 360) recalls Zvyagintsev’s use of actor Konstantin Lavronenko in his first two features, the ever dependable, if flawed, protagonist we’re meant to align ourselves with before circumstances reveal otherwise. An off-screen moment of sexual congress between Lilya and Dimitri is described violently by a child character, a turning point in the film that disbands the threesome that had been anchoring it. Later, when even more tragic circumstances befall them, more off-screen violence leads us to question the integrity and motives of both men.

More than a microcosm of social discord in contemporary Russia, Leviathan is a pointed attack of the current state of affairs brought about under Putin’s regime. A vodka soaked birthday party finds a merry band of hunters using portraits of past Russian leaders as target practice, which Zvyagintsev seems to be doing as well, harpooning both governmental leaders and the insidious influence of the Orthodox church, which becomes more apparent in the second half of the film when we discover the true nature for this struggle over Kolya’s property.

The director has vocally described the film as being inspired by the Book of Job, which is why this chapter of the Bible is discussed overtly within the film, perhaps as way to make sure the unnecessary testing of man, which religion has conditioned mankind to accept and embrace, isn’t lost on us (though if you go into the film knowing Job is the focal point, this conversation does seem a titch forced). Ending as powerfully as several of Tarkovsky’s greatest works, the looming church, (the final, unforgettable shot of Nostalghia, 1983, comes to mind), the multiple meanings of Leviathan direct us most wonderfully to the juxtaposition at hand. Also the name of a classic text written in 1651 by Thomas Hobbes, a political philosopher, who contended there was artificiality to political order, and an innate, natural equality amongst men, a leviathan is also a sea monster, a devouring creature that swallows all for its own survival and dominance. Whether due to apathy, distraction, or conditioned servitude, mankind seems historically prone to being consumed.

Reviewed on May 22nd at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival – Main Competition Section – 141 Minutes

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.