Reviews

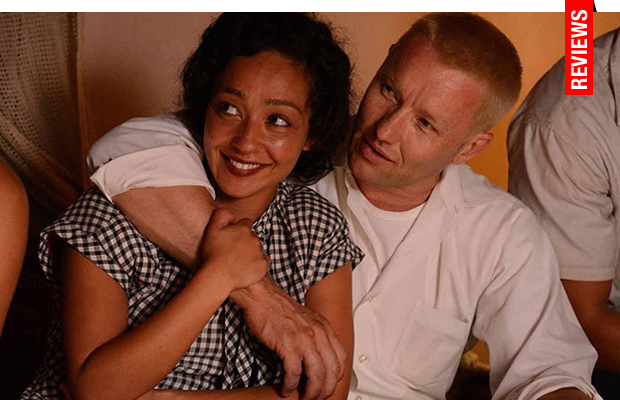

Loving | Review

United States of Love: Nichols Falters with Hokey Prestige Picture

In 1967, the United States Supreme Court made a landmark civil rights decision with Loving v. Virginia, resulting in the overturning of laws prohibiting interracial marriage. The decade long battle was brought before the court by married couple Mildred and Richard Loving after they’d been forced to leave their home state after illegally marrying in Washington, D.C. Without a doubt, theirs is an important, significant, and formidable story worthy of top tier cinematic representation. Unfortunately, Jeff Nichols’ film treatment, Loving, doesn’t do them justice. Though pursuing understated techniques and avoiding a laborious melodramatic court room showdown, the end result forgets to instill their plight with any realism. Unquestionable sincerity casts a sickly pallor over this noble endeavor, but somehow ends up falling into the same trap, albeit from the opposite end of the affluent spectrum, as Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1968).

In 1967, the United States Supreme Court made a landmark civil rights decision with Loving v. Virginia, resulting in the overturning of laws prohibiting interracial marriage. The decade long battle was brought before the court by married couple Mildred and Richard Loving after they’d been forced to leave their home state after illegally marrying in Washington, D.C. Without a doubt, theirs is an important, significant, and formidable story worthy of top tier cinematic representation. Unfortunately, Jeff Nichols’ film treatment, Loving, doesn’t do them justice. Though pursuing understated techniques and avoiding a laborious melodramatic court room showdown, the end result forgets to instill their plight with any realism. Unquestionable sincerity casts a sickly pallor over this noble endeavor, but somehow ends up falling into the same trap, albeit from the opposite end of the affluent spectrum, as Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1968).

In 1960s Virginia, Mildred (Ruth Negga) accepts Richard Loving’s (Joel Edgerton) marriage proposal after they discover she’s with child. The only trouble is, she’s black and he’s white, and interracial relationships were not acceptable. Quietly marrying in Washington, D.C., they keep to themselves among Mildred’s extended family until they’re suddenly hauled to jail by a violent, bigoted sheriff (Martin Csokas) and told by a judge their actions are illegal in the state of Virginia, and so they must leave the state for a period of 25 years or face jail time. Reluctantly abandoning their families, Mildred births three children during their banishment from Virginia. But then a surprise response from a letter she wrote to Bobby Kennedy asking for assistance funds their case forwarded to the ACLU for assistance, and the Loving’s appeal is carried to victory to the Supreme Court.

What’s most disappointing is how widely Nichols misses the mark with this material. True, Edgerton and especially Ruth Negga (who seems more adept at the established tone) manage meaningful, sometimes emotionally authentic moments, but they’re never defined as characters beyond a basic outline of their cause. Take for instance all the other black supporting characters, of which there are many, and you’ll note they are all interchangeable with one another. Sequences with these characters lack in meaning because no connections are established between the Loving’s and everyone else (a slight exception being Mildred’s younger sister).

After five years of living in D.C. with relatives, we don’t even realize another man was living in the home until he sadly waves them off on their way back to Virginia. Worse, there aren’t any scenes in which Mildred and Richard are allowed to seem like a real couple with sequences devoid of any detailing, intimate or otherwise (and one should note the opposite is true for later sequences with the lawyers who ham it up with throwaway asides about borrowing offices or who is parking the car). Period details also seem haphazard, such as a moment in the Loving’s home featuring a contemporary styled interviewer.

In 2016, a year after another landmark Supreme Court ruling finally extended marriage rights to LGBT citizens, it seems a particularly rich period to revisit Mildred and Richard Loving. But as written and directed by Nichols, the kind of psychological complexity experienced by those who have ever been a part of a relationship grossly invalidated by mainstream culture at large is completely lacking.

There’s considerable wear and tear on any long term relationship without the additional weight of battling ignorant attitudes and draining legal battles, but Nichols chooses to place his subjects onto an unrealistic pedestal of perfection audiences have been conditioned to accept as normalizing when it is merely a fantasy breeding false sentiments. Still, this awards baiting material would be an easier pill to swallow if it weren’t for the incredibly clunky dialogue which begins to proliferate exchanges, arriving with the incredibly distracting Nick Kroll and equally miscast Jon Bass as lawyers Bernie Cohen and Phil Hirschkop. “You know this case could change the fabric of the constitution?” one balefully implores the other. Sadly, this pointed dialogue also creeps into exchanges with the otherwise likeable Negga, who tells Nichols’ regular Michael Shannon some eye-rolling elucidation about losing the battles to the win the war as he clicks pictures of her doing the dishes for his LIFE magazine spread.

Corny end titles refer to Mildred as notoriously shy of the press, yet the film depicts her in a completely opposite vein, which seems as if Nichols and his producers weren’t able to see the forest for the trees, focusing so keenly on the importance of the large picture they completely forgot to do justice to the brave humans who lived it.

Reviewed on May 16 at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival – Main Competition. 123 Mins.

★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.