Reviews

Nina | Review

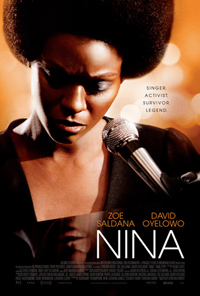

A Matter of Resistance: Mort’s Compromised Portrait of a Musical Legend

She may try with a considerable, ambitious might, but Zoe Saldana does not conjure the complex tragedy of musical icon Nina Simone in Cynthia Mort’s controversially charged and guilelessly titled Nina. Much has been written about the problematic casting of light-skinned Saldana (donning a prosthetic nose and darkened skin to properly convey the black singer) since before the project went into production which was later taken out of the hands of its director’s control. Saldana sings, grimaces, gnashes and pouts as a Simone in decline, this portrait beginning in her latter days following an abdication to France, and a waning career tied to extreme, often violently aggressive call to arms during the late 60s as the voice of the Civil Rights movement. But despite some moments of pronounced mannerism, Saldana remains an eyesore (looking like Thandie Newton after a decade in a tanning booth), an unavoidable distraction underlined by our awareness of the statement made by her casting. Both because of and despite these distractions, the biopic shambles forward in grotesque earnestness, unwilling (or, arguably unable) to present a Nina Simone on her own terms, instead waving a blunted composite neither looking like nor sounding like the late star. It is, at best, an example of misplaced well-meaning.

She may try with a considerable, ambitious might, but Zoe Saldana does not conjure the complex tragedy of musical icon Nina Simone in Cynthia Mort’s controversially charged and guilelessly titled Nina. Much has been written about the problematic casting of light-skinned Saldana (donning a prosthetic nose and darkened skin to properly convey the black singer) since before the project went into production which was later taken out of the hands of its director’s control. Saldana sings, grimaces, gnashes and pouts as a Simone in decline, this portrait beginning in her latter days following an abdication to France, and a waning career tied to extreme, often violently aggressive call to arms during the late 60s as the voice of the Civil Rights movement. But despite some moments of pronounced mannerism, Saldana remains an eyesore (looking like Thandie Newton after a decade in a tanning booth), an unavoidable distraction underlined by our awareness of the statement made by her casting. Both because of and despite these distractions, the biopic shambles forward in grotesque earnestness, unwilling (or, arguably unable) to present a Nina Simone on her own terms, instead waving a blunted composite neither looking like nor sounding like the late star. It is, at best, an example of misplaced well-meaning.

Diagnosed as manic-depressive and alcoholic, once notable soul singer Nina Simone (Saldana) would find herself in a state of denial and decline following her vocalizations during the Civil Rights movement. Though she would officially leave the US in 1970 (her movements streamlined to one eventual move to France for the purposes of this film), Simone met nurse Clifton Henderson (David Oyelowo) while she was restrained and hospitalized in Chicago. Convincing him to leave his post to accompany her to France as her assistant, he reluctantly degrees and a complicated patient/caregiver relationship ensues. But Henderson attempts to reinvigorate Simone’s flagging career, though sometimes she reveals herself to be her own worst enemy.

Mort focuses closely on a particular period in Simone’s life, a reflective time which finds the singer struggling to recapture herself. It isn’t too dissimilar, in this respect, from Don Cheadle’s much more passionate portrait of Miles Davis with Miles Ahead (2015). But she includes snippets of memorable developmental moments (such as Simone as a young girl, insisting her parents be allowed to sit-up front at a recital alongside white attendees), or in the mid-90s when Simone attempted to reclaim royalties for her work. But there is never a clearly defined timeline and the oddly edited feature (credited to Mark Helfrich, Susan Littenberg, and Josh Rifkin, who labored to build this unseemly mound into something significant) causes unnecessary confusion as regards the singer when it should aim to enlighten. Worse, a mawkish score from Ruy Folguera tickles the ivories in a grating ardor to enhance the notable lack of emotional instruction.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, writing in The Atlantic about a month prior to the film’s release, best surmises the problematic realities of Nina. Referring to the choice of the producers to cast a light-skinned black woman, “They did it because they wanted to use the aura of blackness while evading the social realities of blackness.” It’s a powerful, inescapable truth evaded vociferously by the film’s makers. Worse, there’s nothing about the end product which justifies any of the creative choices made, including the evasive flourishes regarding Simone’s sexual appetite, or her extremism.

Those looking forward to a first glance at Mike Epps as Richard Pryor will have to wait for the Lee Daniels project, as here he’s in one sequence, partially in aged make-up, to convey another of the film’s superficial details. Oyelowo may play a sympathetic conduit into Simone’s problems, but there’s not much by way of characterization, dwarfed by the distraction of Saldana (along with notables like Ella Joyce and David Keith portraying his parents).

And perhaps this is the saddest realization of all—Mort’s final product can’t craft any depth, only surface, telling us some of the major details about Simone’s last fruitful period, but never showing us. Saldana, who does a serviceable job singing Simone’s vintage hits, should get credit for such brazenness, but it will only make you want to listen to Simone’s actual tracks in order to dispel the phantom imposter on display here.

Or actually, the saddest realization of all is knowing Nina Simone (as Coates also points out) wouldn’t or couldn’t be cast in her own biopic because black actresses are still, by and large, considered unprofitable in an industry which uses their likeness but refuses to acknowledge or compensate them fairly. And while Simone, undoubtedly, represented different things for different people, such as an affirmation against all the toxic falsehoods we’ve conditioned humans to regard as ‘universal beauty,’ she deserves a more blisteringly authentic portrait than this routine effort musters, the kind suggested by Liz Garbus’ 2015 doc What Happened, Miss Simone?.

While the purpose of repeating all the untoward aspects of Nina shouldn’t be meant to heap blame on its makers, as surely Mort and producers Saldana and Oyelowo meant to honor the singer’s life, it takes an outcry, from all fronts, no matter the skin color or creed or industry, to protest these glaring and inaccurate ‘preferences.’ No matter the beholder, Nina Simone was undeniably beautiful, talented, and fiercely outspoken, both in her prime and her spiraling decline. Nina captures none of her gumption, fury, or resilience and dresses her in a demeaning caricature of a woman too light and too thin to convey her comportment or emotional depth.

★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.