Reviews

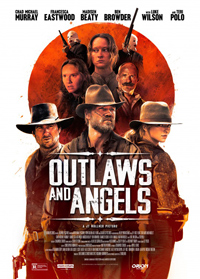

Outlaws and Angels | Review

For a Few Hollers More: Mollner’s Retro Western a Few Cents Short on the Dollar

Opening with Psalm 104:21, “They seek their meat from God,” a mournful narrator ponders the notion of violence and innocence, where the state of one begets or usurps the other in JT Mollner’s period Western, Outlaws and Angels. Although its gentle juxtaposition of a title indicates otherwise, the film is a violent retro-Western, one of many new examples prizing hybridized styles by borrowing tropes already mined ruthlessly during the 1960s and 1970s. A band of bank robbers desperate for shelter hole up in an isolated farmhouse by taking a host family hostage, only to discover they’ve walked into an unexpected viper’s pit. Although not as successful as its ambitious narrative would otherwise imply, the result is an intriguing directorial debut from a writer/director fascinated with regenerating vintage styles.

Opening with Psalm 104:21, “They seek their meat from God,” a mournful narrator ponders the notion of violence and innocence, where the state of one begets or usurps the other in JT Mollner’s period Western, Outlaws and Angels. Although its gentle juxtaposition of a title indicates otherwise, the film is a violent retro-Western, one of many new examples prizing hybridized styles by borrowing tropes already mined ruthlessly during the 1960s and 1970s. A band of bank robbers desperate for shelter hole up in an isolated farmhouse by taking a host family hostage, only to discover they’ve walked into an unexpected viper’s pit. Although not as successful as its ambitious narrative would otherwise imply, the result is an intriguing directorial debut from a writer/director fascinated with regenerating vintage styles.

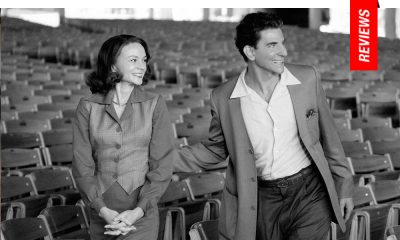

Set in 1887, five masked outlaws rob a bank in sleepy Cuchillo, New Mexico. Having killed someone in the debacle and one of their posse injured, leader Henry (Chad Michael Murray) is desperate to get his men off the road and away from the scent of talented bounty hunter Josiah (Luke Wilson). They stumble upon the isolated Tildon farmhouse, a family far away from any neighbors, many who have been killed or frightened away by an outbreak of consumption. Henry and his men aren’t quite prepared for the dysfunctions they’ve stumbled into, even though it’s easy enough to subdue Ada (Teri Polo), a religious zealot, her husband George (Ben Browder) and their two comely teen daughters, Charlotte (Madisen Beaty) and Florence (Francesca Eastwood). Henry is rather taken by Florence’s beauty, and an inadvertent bond develops.

Opening with a violent bank robbery, which quickly dispatches a perambulating pair of auspicious women and their banal chattering, Outlaws and Angels lands on a familiar spectrum of recent hoary genre efforts, somewhere between the lows and highs of something like Carnage Park and Hell or High Water. Mollner’s screenplay sometimes strikes the correct balance of camp and violence, channeling the legacy of not just the forefathers of the Spaghetti Western, but giallo as well. Of course, this is greatly enhanced by Mollner’s casting of Francesca Eastwood (whose mother, Frances Fisher appears in a minor role), who’s gaze is reminiscent of both her parents. It seems the Eastwood clan is set to headline a number of retro Western hybrids, judging from this and Scott Eastwood’s appearance in 2015’s Diablo, perhaps announcing a cottage genre of its own. But Mollner displays a gleeful predilection for the unhinged, which makes his film entertaining even when it isn’t quite successful at employing grindhouse tactics or embracing efficiency as far as pacing.

Salty dialogue is one thing, but it takes a particular type of performer to make such instances work, and many of the supporting players here struggle with bits of ungainly dialogue. Chad Michael Murray emerges as one of the brighter spots, though perhaps this is sometimes because there’s difficulty discerning what he’s actually saying. The scenario recalls something like Wes Craven’s original The Last House on the Left dressed as a Western, where the tables are turned on the antagonists in the confines of a home invasion thriller. Likewise, from France’s Splat Pack a decade prior, the structure is similar to Xavier Gens’ 2007 Frontier(s). Mollner’s inspirations are at times, too evident, such as having someone using a particularly famous line from Boorman’s Deliverance. Meanwhile, Luke Wilson has the misfortune of starring in the film’s most routine rendering, a bounty hunter defined solely by a dependence on foul language.

DP Matthew Irving has some heavily pronounced frames which astutely recall the heyday of giallo, particularly in focusing on meaningful facial expressions (how he loves these blue-eyed ladies), utilizing intense, significant zooms. Composer Colin Stetson manages a fantastic score, reminiscent of Morricone, but is equal parts brooding and playful (such as an uncomfortable sequence where Polo’s deeply religious matriarch has a sexual fulfilling moment with one of the bandits as her husband pretends to sleep beside her).

But the real highlights here are Eastwood and Teri Polo, who is styled similarly to the pinched alcoholic portrayed by Coleen Gray in 1950’s The Leech Woman. Mollner crunches just enough characterization in for the third act to make sense, but the startling lack of subtlety (we know exactly where all the ‘rub down’ business is heading) isn’t justifiable for a film which bloats at two hours. These slapdash details on the dysfunctional family would be welcome in something a bit more fast and loose, like Jack Hill’s Spider Baby, say. But the ponderous relationship developed between Eastwood and Murray’s tediously scripted anti-hero soaks up too much time and without justifiable payoff. Still, even despite some glaring problems, Outlaws and Angels leans towards the promise of something like Bone Tomahawk and the surprisingly unmined narrative landscape of a dusty genre.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆