Reviews

The Birth of a Nation | Review

Born Again: Parker Resuscitates Turner Narrative in Painful Labor of Love

An odd, continued legacy of unquestioned applause greets the reception of actor Nate Parker’s commendable directorial debut, The Birth of a Nation, a powerful and grotesque revival of a slave rebellion led by Nat Turner, a man who’s most revered account heretofore was a celebrated novel by William Styron. The referenced legacy is in relation to highly regarded depictions of black lives in film and the sort of acknowledgment reserved for an incomprehensibly small number of these items made by or featuring black artists. As a cultural trend concerning the glaring whiteness of another set of Oscar nominees for this year’s ‘best’ efforts in American filmmaking rages on around us, Parker’s film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it took home both the Audience and Grand Jury Prize—but neither its subject matter or its out-the-gate awards prestige offers answers or antidotes. Rather, it continues a serious sort of aggravation.

An odd, continued legacy of unquestioned applause greets the reception of actor Nate Parker’s commendable directorial debut, The Birth of a Nation, a powerful and grotesque revival of a slave rebellion led by Nat Turner, a man who’s most revered account heretofore was a celebrated novel by William Styron. The referenced legacy is in relation to highly regarded depictions of black lives in film and the sort of acknowledgment reserved for an incomprehensibly small number of these items made by or featuring black artists. As a cultural trend concerning the glaring whiteness of another set of Oscar nominees for this year’s ‘best’ efforts in American filmmaking rages on around us, Parker’s film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it took home both the Audience and Grand Jury Prize—but neither its subject matter or its out-the-gate awards prestige offers answers or antidotes. Rather, it continues a serious sort of aggravation.

In the deep woods of 1800s Southampton County, Virginia, Nathaniel ‘Nat’ Turner is taken to meet a clan of Elders, who determine markings on the boy’s chest mean he is to be a prophet for the people. His mother Nancy (Aunjanue Ellis) realizes her son is unusually intelligent and shows an ability to read early on, which she tries to hide from the plantation owners. But Elizabeth Turner (Penelope Ann Miller) takes the boy’s gifts to be a sign from God, and so schools him in the ways of the Bible, grooming young Nat to be a preacher for his people. In 1831, grown Nat (now Nate Parker), is ordered to be a field hand by the plantation owners, now run by the adult Samuel (Armie Hammer). Unrest seems to grow amongst the slaves of neighboring plantations and Samuel decides to loan Nat out along the county to preach to others about obedience. But doing so opens Nat’s eyes to the severe degradation enforced upon these slaves. Eventually, circumstances bring him to organize a rebellion demanding the liberation of his people.

Three years ago, Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale won the same awards out of Sundance, but failed to reach significant box office or enough widespread appeal to claim Oscar glory. But Parker’s film engages on a more historically woeful level, mirroring (at least so far in the eyes of its US distributor, Fox Searchlight Pictures, who were also behind Best Picture winner 12 Years a Slave) the type of film featuring black actors which guarantees Academy votes at the end of the year—the slave narrative (since the US film industry still prizes masculine perspectives, we’ve yet to see Harriet Tubman get the same dues). To utilize a sanitized, academic term, Parker’s depiction of Nat Turner is the very definition of the “African-American” experience, and his usurping of a title claimed back in 1915 by D.W. Griffith (a film perpetuating stereotypes and fears about black people), is the first indication of not only the film’s importance but also its overdue amelioration.

We’re used to seeing narratives of victimization, a mode which Parker’s The Birth of a Nation surely begins with. But Nat Turner’s is a complex narrative challenging notions of moral ambiguity, and Parker doesn’t shy away from moments of deplorable anguish. A young black girl led around by a rope by her white peer; the teeth of a slave chipped out so his white master can funnel slop down his bloody maw and end a hunger strike; the brutal rape of Turner’s wife Cherry, beaten beyond recognition. Many will potentially find these moments too eviscerating, like the corresponding moments of brutal vengeance on white slave owners getting their due—but for each of these despairing detractions, we’re facing truths our contemporary culture has yet to rightly acknowledge, with generations since finding reason to look away or shake off responsibility.

Most powerfully of all, we have a true account of the most infamous slave rebellion to transpire finally brought to troubling, cinematic grace, and for the most part, Parker lands this powerful narrative with aplomb. In many ways, The Birth of a Nation accomplishes what Chris Rock parodies in the 2014 film Top Five, wherein his alter ego presents the box office failure Uprize, depicting Dutty Boukman, the Haitian revolutionary (ironically, Gabrielle Union appears in both films).

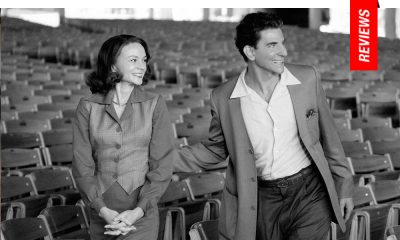

There’s a similar, sinister rhythm shared between The Birth of a Nation and 12 Years a Slave, most evidently between its smattering of white characters and their shades of inhumanity. Penelope Ann Miller is a surprise presence here, teaching the young Nat Turner how to read the Bible (a la a scenario from Sounder, 1972). Armie Hammer is presented as a man who knows better, drowning himself in the bottle. Obviously, the film’s searing heart and soul is Parker himself as Nat, a source of inspiration for his fellow slaves who slowly begins to realize, as he tours the inter-county plantations, he is being used as a tool to fool people into being abused.

Troubling notions of religion as an opiate begin to take shape within the film as Turner astutely realizes one can find a rationalization where one wants to within the ‘good’ book. Aja Naomi King (Four, 2012), Colman Domingo (Newlyweeds, 2013), Roger Guenveur Smith (Do the Right Thing, 1989) and the consistently underrated Aunjanue Ellis (A Map of the World, 1999; Brother to Brother, 2003) are each prominently featured in the superb ensemble cast.

Parker attempts to instill a muted spiritual energy to Turner’s story, presented in brief asides of levitating entities beckoning to him in the forest. The take away in these fleeting moments of a hope existing beyond the degradation of the present is a connection to ancestry and heritage. To look back together now requires the stamina to endure America’s initial sins—but to ignore them is no longer an option. And thus, this is the challenge posed by Parker’s film, featuring a black man who courageously defied an impossible system of imaginary white privilege. Eventually, one hopes we can honor more contemporary truths with the same resounding applause featuring a colorful mixture of humans. But there’s a sense of rightful restoration and acknowledgment here, a more realistic notion of The Birth of a Nation.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Reviewed on January 25th at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival – U.S. Dramatic Competition Programme. 119 Min.

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.