Reviews

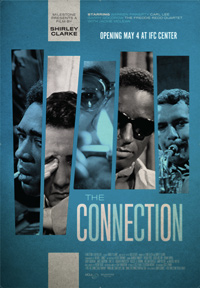

The Connection (1962) | Review

Shirley Clarke’s Infamous 1962 mock-doc on Junkie Squalor gets Restored

‘The Connection,’ Shirley Clarke’s 1962 mock-documentary exposé of New York’s heroin addict sub-culture, has gained a reputation as an era-defining polemic due in great part to being banned after only two screenings. Though its stark depiction of the ugliness of the junkie world is genuinely discomfiting, the ban may have had more to do with two insert shots of pages from nudie mags (straight as well as gay) and use of the word “shit.” Without such automatic censorship triggers, it’s hard to see how Clarke’s “meta” movie, aimed mainly at an insular art world audience predisposed to approve of its provocations, would have posed a serious threat – or revelation – to the social order at large.

‘The Connection,’ Shirley Clarke’s 1962 mock-documentary exposé of New York’s heroin addict sub-culture, has gained a reputation as an era-defining polemic due in great part to being banned after only two screenings. Though its stark depiction of the ugliness of the junkie world is genuinely discomfiting, the ban may have had more to do with two insert shots of pages from nudie mags (straight as well as gay) and use of the word “shit.” Without such automatic censorship triggers, it’s hard to see how Clarke’s “meta” movie, aimed mainly at an insular art world audience predisposed to approve of its provocations, would have posed a serious threat – or revelation – to the social order at large.

In a seedy New York apartment that functions as a junkie waiting room, addicts pass the time flipping through magazines, rehearsing music, and pontificating about the metaphysics of junk addiction until their dealer “The Cowboy” — part shaman, part devil, part nurse, part mortician — shows up with their fix. There’s an undeniable down-in-the-tooth poetry and grim humor to the goings-on, though the truly polemical aspect of Clarke’s movie is her refusal to wholly endorse the sovereignty of sobriety. Just to exist isn’t necessarily being alive, the junkie Solly argues; heroin allows you “to be.” One character’s argument that the vitamin-obsessed “clean” world is just as hooked as the junkies is over-simplified, but makes a point. The central problem of how best to be alive, clean, using, or some other way, is never resolved.

Clarke’s basic preoccupation, however, is to satirize cinema vérité, an insider-y pretense that would have limited the movie’s audience reach, and social impact, regardless of whether or not it was banned or had received more mainstream critical support. The conceit is that all of the film’s footage is being shot by naïve fish-out-of-water documentary director Jim Dunn (William Redfield) and his enigmatic cameraman J.J. Burden (Roscoe Browne, mainly appearing only as an off-screen voice). Dunn earnestly but misguidedly wants to capture the seedy “real reality” of underbelly lives he knows nothing about; he’s mocked for wanting to make a movie about junkies without being one himself.

The parody represented by the Dunn character is the movie’s central element, and by far the weakest. Clarke has Dunn goofily shining lights in the wincing faces of the junkie characters to hammer home her point about the artificiality of his endeavor; the movie reaches the level of caricature when she has him complain, “There is nothing happening visually!” At least Dunn aspires to something uniquely cinematic; Clarke settles for send-up.

Despite its explicit focus on the medium of cinema and its limitations, the movie’s source as a stage play is always apparent. Not only is the action, and the camera, locked into a single set, but traditional playwriting traits persist. Each addict gets his own soliloquy. They’re prone to literate philosophizing: Warren Finnerty’s parasitical middle-man Leach, with his whiny musings and sneering befuddlement at the world’s injustices, is a clear forerunner to a certain kind of disenfranchised American loser, from Dustin Hoffman’s Ratso Rizzo in ‘Midnight Cowboy’ to Steve Buscemi’s Carl in ‘Fargo.’ Leach, in one of many memorable sequences, stares at a naked bulb and wonders why light, traveling at such incomprehensible speeds, doesn’t annihilate everything it comes into contact with. Human beings must be porous, he concludes – but then why do they cast shadows?

Speaking of ‘Shadows’ – Clarke’s movie is often thrown together with John Cassavetes’ groundbreaking first film, released three years earlier, as examples of pioneering American independent cinema. Cassavetes’ movie also intersects with the world of New York jazz musicians and hip bohemian sub-culture. But the similarities end there. Cassavetes went out into the world to shoot his film, and addressed universal issues of identity and community. Unlike Clarke, he had no interest in impressing the intellectual elitists of his day with what cinema couldn’t do; instead, he was passionately driven to discover what it could do.

Distributor Milestone Films is planning a series of releases of Clarke’s work over the next year. Next up in August is ‘Ornette: Made in America,’ a documentary portrait of jazz visionary and harmolodic high priest Ornette Coleman, featuring live performances of his revolutionary Prime Time band. An unavoidable criticism of ‘The Connection’ is that it trades in on the stereotyped association between jazz music and drug use – as if the music were only a symptom of addiction, rather than an artistic expression to be judged on its own terms. But Clarke proved herself superior to these anachronisms by later choosing Coleman as a subject for a movie. His strange and beautiful music (to borrow a phrase from John Lurie) transcends the cultural, social, and artistic boundaries that restrain ‘The Connection.’