Reviews

The Last Gladiators | Review

Fight Club: Gibney Finds Tragedy In ‘Knuckles’ Nilan

The assiduous docu director Alex Gibney wrapped three films back in 2011, all of which seem minor works in his ever growing oeuvre, and the proof is in the lagged theatrical release of The Last Gladiators, which arrives over a year after it’s TIFF premiere. Falling at the tail end of this stream of lighter fare that includes Steve Bartman’s unfortunate baseball foul in Catching Hell, and a drug fueled Ken Kesey tale with Magic Trip, the film details the rise and fall of famed hockey enforcer Chris ‘Knuckles’ Nilan on a quality scale comparable to a mid-grade 30 For 30 title, lacking the political gravitas of Taxi to the Dark Side, the propulsive style of Gonzo, and the intellectual proclivities that pervade them both. That’s not to say Gibney’s valiant salute to his childhood sport of choice and a once beloved hockey tough guy is a complete train wreck, it just doesn’t stand up to the upper echelon docs he’s become known for.

The assiduous docu director Alex Gibney wrapped three films back in 2011, all of which seem minor works in his ever growing oeuvre, and the proof is in the lagged theatrical release of The Last Gladiators, which arrives over a year after it’s TIFF premiere. Falling at the tail end of this stream of lighter fare that includes Steve Bartman’s unfortunate baseball foul in Catching Hell, and a drug fueled Ken Kesey tale with Magic Trip, the film details the rise and fall of famed hockey enforcer Chris ‘Knuckles’ Nilan on a quality scale comparable to a mid-grade 30 For 30 title, lacking the political gravitas of Taxi to the Dark Side, the propulsive style of Gonzo, and the intellectual proclivities that pervade them both. That’s not to say Gibney’s valiant salute to his childhood sport of choice and a once beloved hockey tough guy is a complete train wreck, it just doesn’t stand up to the upper echelon docs he’s become known for.

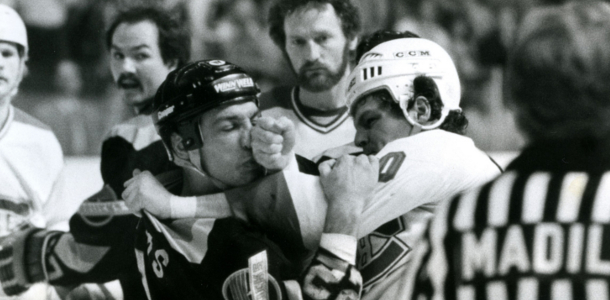

Breaking us in with a barrage of classic hockey fight clips and a hail of praise from notable hockey commentators and famed on-ice muscle the likes of Donald Brashear, Marty McSorley and Tony Twist, we get to know Nilan as an impassioned wreck-loose, a man more than willing to sacrifice blood, sweat and teeth for his team. But unlike many of the hot-headed goons that were merely hired to beat the piss out of anyone who looked at their leading scorers funny, Nilan was also a skilled player with a team leading mentality and a key member of the 1986 Montreal Canadiens Stanley Cup winning team. We also hear from friends and family who provide emotive prospective on his rocky upbringing, filled with fisticuffs not only at school, but with his crestfallen father who sorely gives more weight to the irresponsible fallout that ensued after Nilan retired in 1992, too physically worn to continue competing in the NHL.

Telling much of his own story with a lumbering body of aching bone and meat planted slightly ajar within the frame, Nilan speaks with deeply ingrained pride of his accomplishments on the ice. Under those stonily ridged eyebrows, tears begin to well quite frequently, for the love of the game and the nostalgia he holds for better times now passed. It’s been decades since he heard an entire arena cheering his name or had the opportunity to put a smile on the faces of hospital bound hockey fans, but only a couple years since he was arrested for shoplifting a pair of shorts ‘to save a few bucks’, he told the cops. When his career ended, the former enforcer’s fortunes dried up and he found himself divorced, depressed and drunk, watching soap operas at bars mid-day, hopelessly addicted to the pain killers that kept the ever-present aches and pains at bay. More tears flow from his weary eyes, these ones full of regret and remorse. This is the man his father is ashamed of.

With signature chaptered articulation, Gibney moves amiably from one topic to the next, but in smoothing over unrelated subject matter, the poignantly titled pauses bleed the momentum from the film. It doesn’t help that it’s presented squarely as a linear story that begins hopefully as a tale of one man’s history with hockey’s intrinsic violence and wraps with the somber embarrassment of a broken old man. Like Nilan’s road-worn career and subsequent debauchery and bereavement, the film starts with fists flying and ends with a final chapter of rehabbed pill popping and a fledgling public speaking career that feels a cheap breath of hope where a little more time with Knuckles may have revealed a proper bookend for the film.

You don’t have to look any further than the current headlines of Lance Armstrong or Oscar Pistorius to see some of the physical and mental detriments that could arise in the wake of top tier athletics. Gibney’s disjointed, but affecting testimonial finds in Nilan’s Stanley Cup winning case, bodily sacrifice aggregated home-wrecking alcoholism and substance abuse, taking him from fame to fanatical fiend in the hands of consequent chronic pain and reclusion from the game that made his life worth living. Nilan seems to be turning it around, but others haven’t been so lucky. Though an honest depiction of the untold tragedies that often occur years after the on-ice bouts have been settled, The Last Gladiators feels a bit like its fading star, burning brightly only to be forgotten in the end.