Reviews

Under Electric Clouds | Review

Syndromes and a Century: German Jr.’s Existentialist State of Things

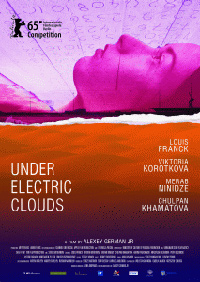

Aleksey German Jr., son of famed Russian auteur Aleksey German, comes into his own prominence with his third feature Under Electric Clouds, which took home a cinematography award following its premiere at the 2015 Berlin Film Festival. Much like his father’s cinema, German announces similar interests in existentialist societal woes impervious to logical narrative format, and exchanges deliberations of the past (his previous title, Paper Soldier takes place in 1961) for the looming future of 2017 (a date that may dawn before the title premieres in certain international markets). With production delayed so German could put the finishing touches on his father’s posthumous masterpiece, Hard to Be a God, this indictment on the decaying cultural state of Russia tuned exactly one hundred years after the Russian Revolution is a critique as obscurely damning as it elusively oblique in tone. Some spectacular imagery providing a backdrop for overly pointed dialogue manages to settle under your skin despite its sometimes mystifying qualities.

Aleksey German Jr., son of famed Russian auteur Aleksey German, comes into his own prominence with his third feature Under Electric Clouds, which took home a cinematography award following its premiere at the 2015 Berlin Film Festival. Much like his father’s cinema, German announces similar interests in existentialist societal woes impervious to logical narrative format, and exchanges deliberations of the past (his previous title, Paper Soldier takes place in 1961) for the looming future of 2017 (a date that may dawn before the title premieres in certain international markets). With production delayed so German could put the finishing touches on his father’s posthumous masterpiece, Hard to Be a God, this indictment on the decaying cultural state of Russia tuned exactly one hundred years after the Russian Revolution is a critique as obscurely damning as it elusively oblique in tone. Some spectacular imagery providing a backdrop for overly pointed dialogue manages to settle under your skin despite its sometimes mystifying qualities.

A skyscraper stands partially constructed as it reaches into the bleak heavens of 2017 Russia. The man who commissioned the structure has died, leaving his disinterested children, Sasha (Viktoria Korotova) and Danya (Viktor Bugakov) to decide its fate—except they don’t seem very good at making choices for themselves. Other people connected to the building, directly and peripherally, find themselves affected by these happenings, including the architect (Louis Franck), an attendant at a museum (Merab Ninidz) forever locked in petty reenactments, and a despondent Kyrgyz gypsy (Karim Pakachakov), wandering about in the unrelenting tundra, where sooner or later, many of these characters also find themselves. Electronic images projected onto the dirty clouds reflect down upon them with eerie promises of normalcy and hope.

German opens his film with a quote from painter Paul Cezanne regarding the relationship between black and white. Cezanne, regarded as an influential artist who bridged impressionism with cubism and influenced future generations of creative minds, like Picasso and Gleizes, experimented with the fracturing of form, which would seem to be the aim of German with this series of eight vignettes each somehow tied to an unfinished skyscraper reaching into the heavens like some skeletal beast (not unlike the whale carcass washed ashore in Zyvagintsev’s 2014 film Leviathan).

Each chapter thematically named and varying significantly in time allotted sometimes makes for uneven tonal shifts, and German veers between black comedy and hyper serious conjecture pertaining to the meaning of life. Several themes begin to take shape, thanks in part to dialogue references about how technology has led to the opposite of globalization. Still, despite these marked cultural shifts over the past century, humans still seem fascinated with the same archaic notions, as evidenced by a particular classism and the need to deride a certain subset of society as ‘superfluous.’ The inheritors of the crumbling vision in the sky, a useless brother and sister engaged with an overbearing uncle, stand in as the melancholy oligarchs, out of time and place. Like Cezanne’s prophetic warning, they’re strikingly juxtaposed with lower class characters, their landscape featuring one of the few moments of levity in German’s film when someone compliments a robot that’s replaced the working ‘superfluous’ class.

Another segment highlights the dangerous philosophical isolation of a new generation’s understanding of the past—one young woman professes to be reading a hypothesis about Hitler and how he wasn’t really such a bad guy, after all. In fact, the tyrant’s treatment of humans he deemed unsavory isn’t too far off from the private criticisms of these misanthropic loners spread throughout German’s landscape, people searching to place blame in an effort to escape an apathetic stupor, a need to get rid of all the ‘dead weight.’

Other scions of literary bygone days have evolved strangely, a flashback sequence features youths clamoring for the works of Georges Simenon and J.R.R. Tolkien, figures now reinvented for complicated live action role playing, where elves are earnestly referred to as actual types of people. German seems to be saying with this society on the precipice of another world war that human culture perhaps requires this cyclical tumult, to be reborn like a Phoenix from the ashes.

Besides recalling the brave new worlds or jarring, disjointed chasms of the past depicted in his father’s work, all the talk of genetic disposition to things like the A.D. gene, or new diseases, like the Peter Pan Syndrome, also seems to channel another of Russia’s most minimized auteurs, Kira Muratova, whose 1990 masterpiece The Asthenic Syndrome documents a new generation of Russian youths afflicted with a contagion of apathy. Stirring, aggravating, and beautiful to behold (despite the divisive quality of the film, there’s no arguing the achievments of DoP duo Sergey Mikhalchuk and Evgeniy Privin), Under Electric Clouds presents a world hanging off a wire, about to plummet into what seems a necessary inferno.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.