Reviews

Wenders Retrospective: Until the End of the World | Review

Pray for the Wounded Planet: Wenders’ Belabored Road Trip to the Apocalypse

The troubled production and following critical ambivalence towards Wim Wenders’ 1991 film Until the End of the World launched it into a sort of oblivion. Nearly twenty five years after its ill-fated reception, initially released as a three hour film which the director bitterly deigned the Reader’s Digest version of his epic, the near four hour and forty minute director’s cut premiered at the 2015 Berlin International Film Festival to coincide with the premiere of his first narrative feature in seven years, Every Thing Will Be Fine. Now, this complete version is finally seeing a US theatrical release courtesy of a fifteen city national touring retrospective of Wenders’ films kicking off in New York at the IFC Center. In retrospect, time has been much kinder to the mishandled title than anticipated. Restored as Wenders’ complete vision, it’s a fantastically ambitious journey that still does not successfully condense its heterogeneous stew of tones, themes, and ideas into a cohesive whole (at least not one justifying this singular narrative), but attains poetic heights in its prophetic final hour, capturing a landscape of technological addiction echoing our modern struggle with increasingly impersonal, self-fulfilling and inward faced interactions.

The troubled production and following critical ambivalence towards Wim Wenders’ 1991 film Until the End of the World launched it into a sort of oblivion. Nearly twenty five years after its ill-fated reception, initially released as a three hour film which the director bitterly deigned the Reader’s Digest version of his epic, the near four hour and forty minute director’s cut premiered at the 2015 Berlin International Film Festival to coincide with the premiere of his first narrative feature in seven years, Every Thing Will Be Fine. Now, this complete version is finally seeing a US theatrical release courtesy of a fifteen city national touring retrospective of Wenders’ films kicking off in New York at the IFC Center. In retrospect, time has been much kinder to the mishandled title than anticipated. Restored as Wenders’ complete vision, it’s a fantastically ambitious journey that still does not successfully condense its heterogeneous stew of tones, themes, and ideas into a cohesive whole (at least not one justifying this singular narrative), but attains poetic heights in its prophetic final hour, capturing a landscape of technological addiction echoing our modern struggle with increasingly impersonal, self-fulfilling and inward faced interactions.

The year is 1999 and the world has gone haywire thanks to an Indian nuclear satellite spinning out of control and threatening to crash into Earth. But Claire (Solveig Dommartin) hardly seems to notice, gallivanting through all-night parties in Venice swathed in haute couture. She has a boyfriend in Paris, Eugene Fitzpatrick (Sam Neill), but they’re about finished thanks to his sleeping with a friend of hers. On her way to meet him at their old apartment, she is involved in a car accident with some bank robbers. She ends up agreeing to smuggle some money for them in exchange for a sizeable profit—now she can afford to buy her own apartment. Eventually, she runs into a strange American, Trevor (William Hurt), and finds herself fascinated. They flirt shamelessly and he disappears. She has to know more, and so she hires a private investigator (Rudiger Vogler) to track him down. Thankfully, he’s already a wanted man. She discovers his true identity, they meet again, and following a sexual liaison, he abandons her once more. Claire continues to chase while Eugene follows behind to make sure all is well with her. Finally, Claire manages to catch up with Trevor/Sam on his way to Australia as he reunites with his parents (Max von Sydow, Jeanne Moreau) in the midst of creating amazing technological adavnces as they hide in caves to escape the nuclear fallout.

As an opening message informs us on the director’s cut, the production ballooned to over twenty million, an unheard of budget for an auteur film. Wenders wished to concoct the ultimate road movie, topping his acclaimed works like Kings of the Road and the Palme d’Or winning Paris, Texas.

Ironically, Until the End of the World works best when it’s stationary, particularly in the final third of the film when grappling with technological advances on the eve of mankind’s extinction within the caves of Australia (a common locale for man kind’s last sanctuary from radiation, a la Kramer’s On the Beach). Up until that point, we’re forced into a dubious romantic triangle illogically nestled into an adventure film noir.

The endless narration of Sam Neill’s lovelorn novelist fills in innumerable blanks Wenders’ ambitious location scouting simply cannot, and so this becomes a laborious process of Claire following the enigmatic William Hurt, first known as Sam, then Trevor, as he engages in a series of mysterious travels (eventually explained, though it doesn’t actually justify all the intrigue it took to get there), who shows little interest beyond sexual arousal. Trailing them both and documenting their troubled romance is Neill (thrown into the mix is Wenders’ cipher Rudiger Vogler as a private dick with an awful lot of silly one liners). From Paris to San Francisco, with a slew of other world cities in between, it’s a gorgeous travelogue until we finally end up in Australia, and then some actual discourse begins.

Wenders crafts an arresting alignment with Plato’s problem of perception and the theory of the shadows on the wall. The apparatus allowing people to transmit images into a machine to create a memory that will eventually be projected into a blind person’s brain results in a bit of ingenious interaction with Plato. Of course, these people are literally shut into a cave, but Wenders and DoP Robby Muller inventively play with shadows and pixilation of these projected images, reinterpreted by a computer, a bit like the process of playing the telephone game and the resulting distortion of assumed meaning of these ‘biochemical images.’

What Wenders manages to nail correctly is the resulting addiction of these technological advances. No sooner is death by nuclear radiation avoided before mankind dives head first into a new obsessions with advanced technology. Wenders crafts Claire and Sam’s all-consuming addiction to deciphering the meanings of their own dreams and projected memories via them being glued to a device that seems a lot like a View Master, and the result is the zombified equivalent of mankind’s global fascination with cell-phones and social media. Technology is ultimately the harbinger of our fate—the more advanced we become, the more we are limited. Until the End of the World plays like the self-fulfilling prophecy of this ‘disease of images.’

“Sometimes the best things happen at the worst of times,” says the blind and melancholy Jeanne Moreau, hinting at mankind’s proclivity to come together only when faced with tragedy. Unfortunately, we’re never led to care much for the human characters here, before, after or during tragedy.

It doesn’t help to know stars Solveig Dommartin (who often resembles Noomi Rapace) and William Hurt loathed one another, and the result is incredibly limited chemistry, especially considering her globe-trot stalk. Her character is framed in demeaning, patriarchal terms, a loose cannon of uncontrollable emotion. When justifying her actions to Neill at one point she says “I’m Claire, what do you expect?” But Dommartin, who concocted this scenario with Wenders before it was scripted by Peter Carey and Michael Almereyda, never quite manages to make Claire’s unruly nature evident.

A member of the indigenous Australian tribe guiding Claire and Sam to his father’s caves hums a song at one point. Hurt explains the man’s inspiration to sing about their surroundings, as ‘everything is part of the story,’ and this particular man is a ‘custodian of this part.’ If that’s the case, there are too many custodians wandering about in Until the End of the World, a beautifully rendered but unnecessarily protracted pilgrimage of advancement as our ultimate undoing.

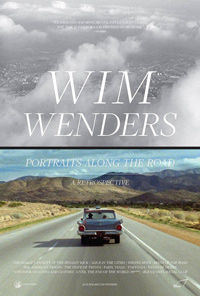

Reviewed on August 30 at the 2015 Wenders Retrospective “Portraits Along the Road.” 295 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.