Reviews

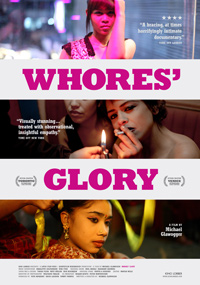

Whore’s Glory | Review

Sugartime: Michael Glawogger Brings Us a Bleak Look at Third World Brothel Workers

If Michael Glawogger’s Whores’ Glory, the third installment in his trilogy of globalization documentaries, (following Megacities, 1998, and Workingman’s Death, 2005) plays like a vulgar and unsuitably stylized triptych of the grotesqueries of sex work, it’s because no amount of enhanced aesthetics should let you ignore the reality of the subject matter. His intentional choices rather stress instead that any attempt to do so only causes closer inspection of the obvious. With a title suggesting empowerment, we quickly observe that Glawogger’s latest, while not showing us anything we shouldn’t already be able to realistically imagine ourselves, is being facetious. There’s no glory to be realized, but the repetitive hellishness of these women’s stories reveals the bleak realities of base humanity, and is told with an effort that’s at least realistic in nature, void of hope.

If Michael Glawogger’s Whores’ Glory, the third installment in his trilogy of globalization documentaries, (following Megacities, 1998, and Workingman’s Death, 2005) plays like a vulgar and unsuitably stylized triptych of the grotesqueries of sex work, it’s because no amount of enhanced aesthetics should let you ignore the reality of the subject matter. His intentional choices rather stress instead that any attempt to do so only causes closer inspection of the obvious. With a title suggesting empowerment, we quickly observe that Glawogger’s latest, while not showing us anything we shouldn’t already be able to realistically imagine ourselves, is being facetious. There’s no glory to be realized, but the repetitive hellishness of these women’s stories reveals the bleak realities of base humanity, and is told with an effort that’s at least realistic in nature, void of hope.

Opening with a poem by Emily Dickinson, whose own hermetic existence seems more appropriate for the nunnery than the brothel, we’re quickly deposited into Bangkok, the first of three very different locations. The poetic prologue quickly dissipates into the harsh neon world of The Fishtank, where women are selected via a number system by clients on the other side of a pane of glass. A song by Tricky called Taxi (White Boy) plays over bodies dancing, “Get me a white boy so I can have white joy.” We meet a number of the women, hear them pray for more clients, entertain themselves, ponder their longevity in their profession. Tracks by freak folk artists CocoRosie and crooner Antony and the Johnsons provide eerie atmospherics over the flashing lights. And as if borrowed from one of fellow Austrian Ulrich Seidl’s films, we’re treated to an extended sequence of dogs rutting, painful yelps and all from what looks like nature’s version of a gang bang.

Next, we’re jettisoned to Bangladesh, where the girls are even younger and with even less agency. Living in squalor, we get less soundtrack (though PJ Harvey tracks surface) and more frenetic noise, the customers and the details of their wishes and needs even more vile and disturbing. Young women aggressively handle each other and their customers, with babies lying in the streets outside their doors. And finally, the most severly grim locale is a rural area in Mexico called The Zone. The women here seem to be more in control of their bodies than their Bangladesh counterparts, but their surroundings are desolate, their options of mobility seem null and void. It’s here where drugs are the best form of escape. While we’ve been privy to Glawogger’s interviews with the johns in the prior segments, the overly aggressive and hostile men cruising The Zone are more putrid and disgusting in their disparaging and violent attitude towards the women. It is in this segment where Glawogger films a john having sex with a prostitute, a handheld camera providing us with intimate details. When the sex worker kicks the john out for taking too long to orgasm and not having more money, we’re left wondering if he would have left so quietly if the camera hadn’t been there.

Whores’ Glory stands as one of the more aesthetic documentaries about the world’s oldest profession, but the women we’re invited to share time with are mostly unhappy victims that would be doing something else if they had the option, a wish most vocalized in the Bangladesh segment. All the johns and a few of the prostitutes postulate that their profession is a necessary evil. While Glawogger doesn’t offer any counterarguments, it’s obvious that sex work is more often than not a rough, hard-knock life, a certifiable strenuous existence that seems baffling to the unexposed. It is a life of constant disposal and consumption. Despite its grim subject matter, Whores’ Glory features a killer soundtrack, stylized editing for each segment, and a bluntness in its depiction of the subject that’s neither demoralizing nor judgmental. Glawogger’s latest slice of global miserableness may not be eyeopening, but it’s honest. To bookend his feature, Glowagger could have entrusted us with more wisdom from Dickinson with her quote, “I like a look of Agony,/Because I know it’s true-/Men do not sham Convulsion,/Nor simulate, a Throe-.”