You Were Never Really Here | 2017 Cannes Film Festival Review

Where Have You Been?: Ramsay Returns with Pronouncedly Fractured, Melancholic Adaptation

Returning from a six year hiatus after 2011’s We Need To Talk About Kevin, Scottish auteur Lynne Ramsay delivers a career best with a poetically fractured adaptation of Jonathan Ames’ novel You Were Never Really Here. Evoking a Joyce Carol Oates rhythm of a war veteran who’s been suffering from PTSD symptoms since childhood and since morphed into a violently inclined assassin/enforcer, Ramsay streamlines B-genre narrative tropes into an efficient and emotionally potent psychological portrait which recalls the woozy style of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011) remixed with Paul Schrader’s 1979 Hardcore. Building on the nostalgic essence of the oft mimicked era of New American Cinema, this mostly dialogue free exercise is laced with themes of awakening and atonement in a fretful world filled with pain, heartache, and the ultimate reality of our expendability.

War veteran Joe (Joaquin Phoenix) works as an enforcer for a mysterious employer (John Doman) and lives with his elderly mother (Judith Roberts). When he is tasked with recuperating the runaway daughter of Senator Votto (Alex Manette), currently in the middle of an election with rival Governor Williams (Alessandro Nivola), Joe finds the preadolescent Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov) has been recruited into a child prostitution ring which is inextricably linked to both parties. After successfully completing his mission, some surprise twists occur, prompting Joe to rescue the young girl of his own accord.

The title credits of You Were Never Really Here flickers over the mouth of a taxi driver singing to a song on the radio as Phoenix’s Joe is in the middle of completing another assignment as a hired gun. The reverence of vintage pop music is a running motif in this eerie mood piece, and paired with a soundtrack from Johnny Greenwood, confirms the power and suggestive properties of memory and song.

We learn just enough of Joe to understand why he’s the empty shell of a man he is today, having survived a horrific childhood where he and his mother were significantly abused by his father. A brief memory of sickening violence from his service in the military (circa 2003 based on the Christina Aguilera track playing) confirms his passion to assist vulnerable victims of circumstance.

After a brief snafu with the son of a middle man seeing Joe in the wrong place at the wrong time, he settles into a comforting rapport with his mother (an excellent Judith Roberts of Lynch’s seminal freak show Eraserhead, 1977), engaging in patterns of control and stability established by his penchant for asphyxiation and moderated countdowns. These mind games align Nina and Joe as likened souls with a similar pattern of survival skills.

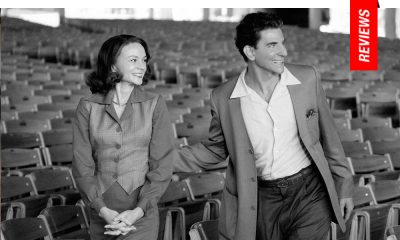

DP Thomas Townend (Attack the Block, 2011) constructs two moody swoon sequences of carnage set to the soulful track “Angel Baby” from Rosie and the Originals. The first depicts Joe’s killing spree from the black and white vantage point of the security cameras in the compound where Nina is kept. The sequence is repeated in color during a climax which is used to indicate how Joe’s romantic ideations of his profession have taken on more personal and meaningful dimensions. When assassins visit his mother’s home, this idea of connection and redemption existing within the brief fumes of a melancholy pop song are repeated when killer and victim sing quietly along with a song on the radio and hold hands briefly—as the title indicates, none of us are ever really here except in our own minds and memories, expiring with the self.

Emotionally more substantial than the moody equivalent of something like Refn’s Drive, Ramsay will most likely draw comparisons to Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, but this alignment isn’t quite right considering the empathetic dimensions of Joe, even if he is rather a familiar composite of the wide-eyed hollow souls we’ve seen Phoenix embody time and again.

Ramsay, whose films often provides a visual roadmap reflecting her character’s interiority, takes You Were Never Really Here into the similar realm of 2002’s Morvern Callar in its resistance of standard narrative formatting. Phoenix’s sulky assassin is akin to the fatherly George C. Scott of Hardcore, who searches in vain for a daughter who’s disappeared willingly into the seedy underbelly of New York City. Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here lands on the difficulties in overcoming irreparable damage caused by trauma and abuse in beautiful but abstract visual fragments.

Reviewed on May 26th at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival – Main Competition. 95 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.