Reviews

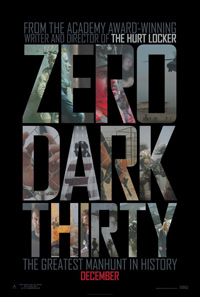

Zero Dark Thirty | Review

Mourning the Mythic: Revenge has no Taste in Bin Laden Hunt Film

Director Kathryn Bigelow willfully reigns in her own mythologizing instincts in the harrowing ‘Zero Dark Thirty‘ to present an unmediated “real reality” of the terrible, terribly ordinary violence which men and women perpetrate in the 21st century. Depicting in exacting detail the CIA’s 10-year manhunt for Osama Bin Laden, including the final Seal Team mission targeting bin Laden’s Pakistan hideout, the majority of the film is a nervy detective story stressing the white-noise confusion of contemporary intel gathering and timeless lessons on the impossibility of knowing anything, really. But in an abrupt twist, Bigelow adds a final-act execution sequence—No American action movie has ever come as close to being a snuff film. Though Bigelow and screenwriter/producer Mark Boal disable the usual action-movie cathartic climax, they take no joy (or as in Michael Haneke’s adolescent ‘Amour,’ smug superiority) in withholding this desired release from their audience. Instead, they mourn the failed possibility for such catharsis, and along with it cinema’s lost myths, its capacity to transcend, and not just depict, lived reality.

Director Kathryn Bigelow willfully reigns in her own mythologizing instincts in the harrowing ‘Zero Dark Thirty‘ to present an unmediated “real reality” of the terrible, terribly ordinary violence which men and women perpetrate in the 21st century. Depicting in exacting detail the CIA’s 10-year manhunt for Osama Bin Laden, including the final Seal Team mission targeting bin Laden’s Pakistan hideout, the majority of the film is a nervy detective story stressing the white-noise confusion of contemporary intel gathering and timeless lessons on the impossibility of knowing anything, really. But in an abrupt twist, Bigelow adds a final-act execution sequence—No American action movie has ever come as close to being a snuff film. Though Bigelow and screenwriter/producer Mark Boal disable the usual action-movie cathartic climax, they take no joy (or as in Michael Haneke’s adolescent ‘Amour,’ smug superiority) in withholding this desired release from their audience. Instead, they mourn the failed possibility for such catharsis, and along with it cinema’s lost myths, its capacity to transcend, and not just depict, lived reality.

As she has done before in her exhilarating, adrenaline-powered oeuvre—most recently in ‘The Hurt Locker‘—Bigelow provokes our appetitive desire for action, risk, and violence. But never before has she so scrupulously countered it with appetite’s twin, disgust. Featuring scenes of “enhanced interrogation,” the movie is itself a mild form of torture; Bigelow sickens us not with gore, but with the unreverberating banality of real-life killing. Cinema has always been fascinated by, and wary of, the attempt to capture the immediate reality of death (Hitchcock, ‘Peeping Tom,’ ‘Videodrome,’ etc.). Bigelow and Boal recognize it as a Faustian bargain. They show us the profound, even metaphysical, despair that follows not only the destruction of human life, but the abandonment of imagination for plain facticity. Bigelow’s movie is not an argument against violence in movies; it is instead a surreptitious rejection of 21st century film’s demolishing trend towards de-mystifying, de-mythologizing, and degrading human life under the guise of transparent “realism.”

In Jerzy Skolimowski’s masterful ‘Essential Killing,’ Vincent Gallo’s Taliban prisoner, captured and tortured by American military forces, escapes to embark on an existential, mystical journey of pure survival—the movie is totally oblivious to political agendas. Similarly, violence was mystically inevitable in Bigelow’s masterpieces ‘Near Dark,’ ‘Blue Steel,’ and ‘Point Break.’ In ‘Zero Dark Thirty,’ by contrast, violence is necessary, but managed by bureaucracy—a corporatized strategy decided upon by “cowed” middle managers looking to defend their jobs, while the face of the company—President Obama—cluelessly disavows all knowledge of the messiness occurring under his watch. Bin Laden is executed by likable, brave soldiers—the audience yearns to get vicariously behind them as if they were the marines in James Cameron’s ‘Aliens‘; but somehow, in their mercenary amenability, they fall short of being classically heroic.

As with Jamie Lee Curtis’ rookie cop in ‘Blue Steel,’ Jessica Chastain’s CIA operative Maya is a woman with the strength of her convictions, moral and otherwise, trying to find her place in a male-dominated culture of violence. But unlike with Ron Silver’s lover/mentor/psychopath, radiantly alive with madness, Bigelow resists elevating Osama Bin Laden into the archetypal stratosphere. His code name is Geronimo, but he isn’t a noble enemy, or a worthy opponent; he’s just a target; a beard in a body bag; his death is swift, unceremonious, and unfulfilling.

Myth purges and transmogrifies the destructive impulse; it doesn’t provoke real-life murder. Only in the secular void left by the eradication of myth does violence become as rational a choice as any, as easy as hitting send. Bigelow builds up momentum towards a big action-movie finale, and then shows us what real “essential killing” looks like: crude, unclimactic, impersonal, nauseating. The common complaint about movies used to be that they glorified violence. Are we now left with an even more disturbing, inglorious alternative?