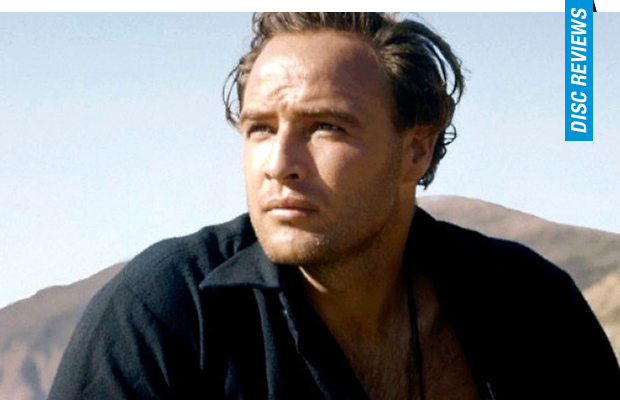

Bank robber Rio (Brando) and his friend and mentor Dad Longworth (Karl Malden) rob a bank with Doc (Hank Worden) in Sonora, Mexico. Celebrating after they successfully steal two sacks of gold, the trio is accosted by authorities in a cantina, ending with Doc getting killed while the other two escape. Cornered on a precipice, the two toss for one man to take the remaining pony (and the gold) down the canyon and return with provisions for the man left behind. Dad takes their pony but never returns to rescue Rio, leaving the younger man to be arrested by authorities and hauled off to prison, where he learns firsthand of Dad’s betrayal. After five years in the Sonora prison, Rio breaks out with Chico Modesto (Larry Duran) and goes hunting for his old partner, who he finds has used their money to establish himself as the Sheriff of Monterey, California. Plotting to take his revenge by robbing the Monterey bank alongside Bob Emory (Ben Johnson), Rio is sidetracked when he meets Dad’s wife Maria (Katy Jurado) and her virginal daughter, Louisa (Pina Pellicer), who he finds himself instantly smitten with.

There are pronounced parallels in Brando’s characterization in One-Eyed Jacks and the project he’d completed just prior to production, Sidney Lumet’s glorious The Fugitive Kind (1960), an adaptation of the Tennessee Williams play Orpheus Descending. In Lumet’s film, Brando was a tortured but rugged vagabond, a man who courted and corralled vice, eventually seducing and falling for a married woman (an absolutely phenomenal Anna Magnani) whose life has been significantly marred by her older, abusive husband, who controls the small town they reside within.

Brando seems to have willed a bit of Williams’ motifs into One-Eyed Jacks, refusing to allow his broken bank robber Rio to be viewed as villainous, instead morphing him into a misunderstood lothario with problematic daddy issues (the naming of the Karl Malden character is easily the creepiest bit of textual brilliance) and the kind of forbidden and simultaneously eyebrow raising romantic connection Williams was known for (including, of course, the certainty of a pregnancy). At the same time, Brando holds the brooding level at a maximum throughout, and Rio is presented as a tragic Shakespearean figure, like Hamlet reimagined as a bank robber.

DP Charles Lang scored his fifteenth of eighteen Oscar nominations for Best Cinematographer, and One-Eyed Jacks is, without a doubt, a picturesque Western speckled by flurries of turmoil, such as a beautiful late staged sequence where Rio recovers after a vicious beating by plotting vengeance near the roiling seaside. Despite the agony over the casting of Rio and Dad, Brando did assemble a sterling supporting cast, including a series of notable character actors, with brief appearances from Timothy Carey, Miriam Colon, Elisha Cook Jr., and Ben Johnson (faces who would populate the New American Cinema movement of the 1970s, in films by Cassavetes, Peckinpah, Penn, etc.).

A young-ish Slim Pickens (who would also star in Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kidd with Katy Jurado) brings his particular accentuations as a leering Deputy, and the script would seem to hint at his barely concealed designs to have Louisa for himself had Rio not come along. Malden was always a master at portraying a frumpy manipulator, whose nastiness is unprecedented for such a dowdy veneer, and his maneuvering, two-faced Dad Longworth is nearly as evil as his cotton farming sex-hound from Elia Kazan’s Baby Doll (1956). Backing him up is the beautiful Kathy Jurado (an Oscar nominee for Edward Dmytryk’s Broken Lance), a Mexican actress often cast as a way to build some authenticity, perhaps best remembered as the ex-mistress of Gary Cooper in Zinnemann’s seminal Western High Noon (1952).

Brando’s real discovery is Pina Pellicer, making her English language debut, who instills a barely conceived romance with a believable anxiety and neuroticism for an inexperienced girl swept off her feet by a potentially dangerous drifter. Pellicer would appear in only two more features before committing suicide at the age of 30 in 1964.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents the title with a new 4K digital restoration, a process undertaken as a partnership between The Film Foundation and Universal Pictures, while Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg were involved in the consultation process. Available in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1 from the original 35mm and the VistaVision negative (this was the last title to be filmed in VistaVision), it’s an incredibly clear transfer void of visual tarnish. Criterion includes several extra features, including a new introduction courtesy of Scorsese.

Martin Scorsese:

The Film Foundation recorded this new three minute introduction by Martin Scorsese in 2016 when the new restoration of the film was presented at the Cannes Film Festival.

Marlon Brando:

Brando made voice recordings of his ideas for every scene, and this thirty-three minute segment features excerpts from his audio recordings and highlights differences between the completed product.

A Million Feet of Film:

1950s western blogger Toby Roan wrote and recorded this video essay on the production of One-Eyed Jacks, a film he has been gathering memorabilia from and facts about since 1978.

I Ain’t Hung Yet:

Filmmaker and critic David Cairns examines the framing, editing, and other storytelling devices used in One-Eyed Jacks for this visual essay.

Final Thoughts:

One-Eyed Jacks, like Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter or Eddie Murphy’s Harlem Nights, is one of those offbeat blips which owes its pronounced and particular accents to the ambitious perspectives of a talented actor turned director, and is all the more intriguing as Brando’s only attempt at controlling the scenery from behind the camera (and perhaps explains some outrageous behaviors from the actor in later years).

Film Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆