Bathed in an eerie glow of mysticism, Kaneto Shindô’s Kuroneko is a haunting and sensual tale about the nexus of the spiritual and physical worlds. Kuroneko has often been labeled as a horror film, a tag that seems woefully insufficient; akin to describing Syndromes and a Century as a medical drama. Within its delicate folds, Kuroneko presents a romantic ghost story of bloodlust, revenge and karmic justice, driven by solemn bargains between tortured souls and ancient malevolence. A stalwart hero will bravely battle the specters of evil, and be rewarded for his efforts with unimaginable heartbreak and crushing despair. And viewers able to overlook those moments when Shindô’s imagination exceeded his technical grasp, will be rewarded with an unforgettable journey into a seductive but forbidden realm.

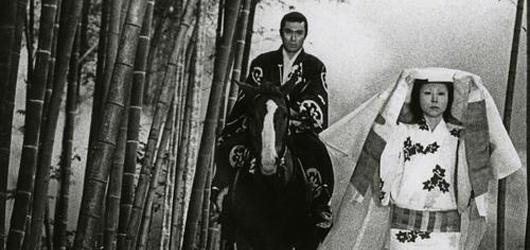

Set in Japan’s feudal era, Kuroneko opens with the pastoral image of a straw hut amid a gently swaying field of grain. A group of hungry and battered samurai emerge from the nearby bamboo forest, and stealthily approach the tiny farmhouse, swords and lances drawn. Inside are two women: a young bride named Singe (Kiwaco Taichi) and her mother-in-law Yone (Nobuko Otowa) preparing to eat a meager lunch of cold rice. The pair has been left alone at the farm, struggling to make a go of it, ever since Singe’s husband was kidnapped and pressed into service as a soldier. The samurai charge into the hut and the terrified women can only stare as their simple home is ransacked. But the solders are not satisfied by a little rice and a few pieces of silver, and Yone and Singe are subdued, savagely raped and left for dead. For good measure, the samurai set fire to the tiny house, and the timbre and straw structure ignites in violent inferno reminiscent of Hiroshima.

Shindô practices a brutal economy in these establishing scenes, with damning close-ups of the participants that render them utterly devoid of humanity. He has quickly set the table for revenge, but the eventual doling out of justice will be like a slowly savored dream; with multiple courses of shocking and surreal discoveries. Throughout the film, Shindô mixes the barbaric with the serene, the sybaritic with the spiritual, creating a brooding atmosphere of powerful, unseen forces locked in cosmic conflict. A few years later, when corpses of high ranking samurai begin appearing in a misty bamboo forest, their bodies drained of blood, local warlord Raiko (Kei Satô) fears the murders are the handiwork of dark forces, disguised in the apparition of a beautiful young woman. He issues an urgent dispatch to his champion Gintoki (Kichiemon Nakamura), swordsman extraordinaire, to return and act as ghost detective, with the power to dispatch justice with his speedy blade. But as Gintoki slowly peels back the suspect’s mysterious layers – and her diaphanous kimono – he makes a stunning discovery that transforms this powerful warrior into a quivering mass of indecision. In order to complete his sacred mission, he must endure a spectacle of unimaginable loss, and sentence those he loves to a torturous eternity.

The film contains many striking and exotic images, including a foggy bamboo forest that serves as a connector to the spiritual plane, rendered with an effective nightmarish air. A wide shot of Gintoki racing through the desert while an enormous sun shimmers in the background is an arresting image worthy of the finest graphic novel. And a mysterious country house, which serves as the film’s primary killing field, appears to float atop a sea of bamboo, while moonlit clouds scurry overhead like an approaching storm. Kuroneko translates roughly as “Black Cat”, but it’s a rather forced metaphor, as the occasional sight of a kitty crawling over the corpses of murdered samurai is more amusing than frightening. Shindô’s other misstep is an over reliance on the primitive flying rigs often used in Kabuki theatre. His carefully built atmosphere of foreboding is nearly ruined when his assorted banshees start flailing about in space; their suspensions plainly visible in one scene. It’s a testament to Kuroneko’s power that the film survives these theatrical distractions to remain a rewarding, and highly recommended, cinematic experience.

Kuroneko is a film that somehow manages to be both stark and lush, and Criterion’s transfer successfully captures the sinister etherealness of Kaneto Shindô’s vision without delivering a murky presentation. With an aspect of 2.35:1, the disc’s high contrast will severely test the limits of most displays, but the transfer strikes an amazingly good balance of powerful, condensed blacks and melancholy grays. And, as usual for Criterion, sharpness and cleanliness are beyond reproach.

The mono mix features a pleasing modern presence, with the drums from the opening title sequence producing impressive sound stage. Hikaru Hayashi’s thoroughly creepy score is sparingly used, but each chilling note sounds just about perfect.

Video interview with director Kaneto Shindo from the Directors Guild of Japan

This massive interview, 60 minutes in length, will prove conclusively that Kaneto Shindo really doesn’t mind discussing himself. And at age 86 – at the time of the interview, he’s now 99 and still making films – it’s a privilege he’s earned. We learn all about his early days as a washer at a film lab and his desire to become a director. In those days, discarded scripts were used as toilet paper, and Shindo taught himself to write by actually reading the old screenplays, as opposed to their improvised purpose. He didn’t direct his first film until age 40, but in the interim he’s compensated by becoming one of the world’s most prolific filmmakers. The interviewer, an intimidated former assistant, doesn’t do very much to keep Shindo on track, so the diatribe pursues a variety of avenues. There’s very little here specific to Kuroneko so this supplement will likely be of marginal interest to all but Shindo fanatics.

New video interview with critic Tadao Sato

Sato adds unique perspective that most Western viewers will find of value. Every summer, Japanese theatres saw an influx of ghost movies, timed to coincide with a Buddhist holiday honoring the dead. Kuroneko was part of that tradition, and Sato points out several elements of the film firmly rooted in Buddhist beliefs. A number of the characters were based on actual historical figures, giving Kuroneko a deeper resonance with Japanese audiences. Sato’s comments will be of interest to anyone interested in Asian religious culture and, at 17 minutes, it’s a concise and worthwhile bonus.

Theatrical trailer

The trailer is an effective distillation of Kuroneko’s darkly magical moments, although a few of the sillier scenes slip in too. The trailer comes awfully close to spoiling, so it’s not recommended for viewing prior to the feature.

Booklet featuring an essay by film critic Maitland McDonagh and an excerpt

from film scholar Joan Mellen’s 1972 interview with Shindo

At a hefty 30 pages, the booklet has lots of interesting information along with numerous film stills. McDonagh’s essay is beautifully done, and tracks Kuroneko’s influence on a host of other, better known, Japanese horror films. Mellen’s interview is much more precise and targeted than its video counterpart, and we learn more about Shindo’s interest in psychology and American cinema. Credits and extensive notes on the transfer complete the edition.

Romantic ghost stories have been around throughout the history of cinema. But 1968’s Kuroneko is distinct for its erotic undercurrents and disturbing sense of alien, forbidden obsession. The unleashed passions of the damned will cause a proud warrior to face an impossible dilemma, and insure his own emotional destruction. Kaneto Shindô’s heartbreaking tale is not flawless, but its imperfections and awkward moments only add to its rich character and haunting, dreamlike qualities. When the worlds of spirits and humans collide, as Kuroneko makes clear, both realms ultimately suffer.

Reviewed by David Anderson