A famous designer of high fashion women’s wear, the imperious Petra Von Kant (Margit Carstensen) lords over her private manor with the assistance of her slavish maid, Marlene (Irm Hermann). Waking up, she immediately dons a chic, fur lined item and a wig that we’d later see again on Tina Turner. We’re unsure if this is her permanent residence or a creative retreat—either way, she leaves the busy work to Marlene, charged with serving her mistress in-between sketching garments and typing dictation. A guest drops in, Sidonie (Katrin Schaake), a high society gal that seems to have, at one point, been close to Petra. They commiserate on Petra’s bed, the only place, it seems, to sit. Sidonie has recently been married and Petra relates tales about her own marriage to Frank, which had ended in divorce because he couldn’t deal with the notion of equal gender roles and open communication—all things Petra prizes. Sidonie disagrees—we have standard roles of behavior already in place, why make it hard on yourself? “I let him think he’s the boss,” she comments on her husband. But Petra believes ‘marriage brings out the worst in people,’ and criticizes Sidonie. “That’s how oppression comes about, quite accidentally.”

A friend comes to meet Sidonie, Karin (Hanna Schygulla), fresh from Australia, trying to make her way in Germany. Petra is instantly taken with Karin, inviting her back the next night for some fittings, the aim being morph her into a catwalk sensation. Karin shares personal stories from her troubled family life, and by the end of their second conversation, Petra confesses her love. We skip ahead in the next scene with a new wig for Petra to denote the passage of time—her relationship with Karin already in shambles. Another prolonged conversation ends with Petra’s abandonment. Then, we move to her gin-soaked birthday party, bed removed, blonde wig in place, and party guests that include her daughter (Eva Mattes), mother (Gisela Fackeldey) and good old Sidonie. Their false comforts do little to assuage the distraught Petra, who wants nothing more than for Karin’s return.

If this all sounds melodramatic, it’s because it is, and clearly these are the inspirations of Sirk’s soapy scenarios. But the heteronormative stronghold of Hollywood always created a notable absence of onscreen desire, straight or otherwise, which Fassbinder conflates and subverts into a vacuum that seems perverse in direct comparison. The film could have easily been called Designing Women, thanks in part to Petra’s occupation as well with the film’s drenched motif of artificiality, and how relationships are all poses meant to maneuver and inevitably control not only your space, but the humans sharing it. In Peter Matthew’s essay, “The Great Pretender,” he cites the opening credits of the 1939 George Cukor classic and how it compared the all female cast to corresponding animals. Fassbinder opens with a pair of felines on Petra’s stairs, as segue into Petra’s own den, where only she will be master and commander.

The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant has to be one of the most overlooked and maligned titles in Fassbinder’s extensive filmography. It stands as Margit Carstensen’s most iconic role, and she dominates the film in every frame, recalling the imperious power of studio era Joan Crawford. While Schygulla is most often cited in discussions pertaining to Fassbinder, this is one of the few titles where she’s dominated by another Fassbinder muse. Irm Hermann actually appeared in more of his films than any other, here a wordless entity, a willing slave to Petra until the very end. Her Marlene is like the stepping stone from the world of the mannequins to the women in Petra’s bed chamber, an evolutionary link between the primordial swamp and the semi self-actualized.

Disc Review

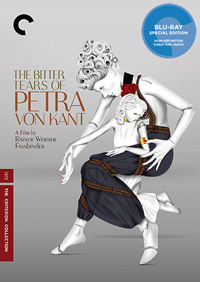

For fans of Fassbinder and this phenomenal title, one couldn’t wish for more than Criterion’s 4K digital restoration. The cramped, superficial mise-en-scene gets a vibrant up-do compared to the previous DVD edition from Wellspring. A new title in their collection, Criterion nabbed several 2014 interviews with scholars and cast members, as well as including a 1992 documentary from German television.

Outsiders:

A thirty minute segment of interviews features new commentaries from Margit Carstensen, Eva Mattes, Kristen Schaake, and Hanna Schygulla, Each actress relates how they felt somehow disassociated with the project, starting with Schygulla who stated she felt as if she were in a trance during filming because she disliked the role, to Mattes, who at such a young age did not feel as fully invested in Fassbinder’s circle. Schaake speaks about her discomfort with Fassbinder at times (including his ‘truth’ game), while Carstensen claims she felt she was always the perpetual ‘outsider.’

Ballhaus Interview:

A seven minute segment features DoP Michael Ballhaus, who relates his surprise at being rehired by Fassbinder for a third time (their first collaboration on Whity was not a cherished experience) as well as the difficulties of filming in the lone, cramped setting.

Jane Shattuc Interview:

An interesting new interview with scholar Jane Shattuc discusses Fassbinder’s work and hoe he ‘self-consciously looks at beautiful women suffering.’

Role Play: Women and Fassbinder:

A fascinating 1992 documentary for German television features cast members Carstensen, Schygulla and Irm Hermann, who relates very interesting tidbits about Fassbinder’s differing relationships. She was very invested with him at the time, and says during those days she was described as hysterical, the director always keeping her on edge and engaging in a strange power play. Hermann admits he was not this way with Hanna Schygulla, who appears to state that they were all pawns on Fassbinder’s chessboard, and while he didn’t film reality, his films would ‘expand on his own personal universe.’ And then, Margit Carstensen takes the credit for the negative portrayals of femininity, which she claims was all her doing. “I don’t trust any woman,” she sniffs.

Final Thoughts:

Petra unwittingly becomes the very victim she seems to criticize Sidonie for being in the film’s opening conversation, her relationship with Karin positioning her as the weaker, needy one. Cultural conversations concerning the film tend to position it in the same ‘art-house’ class as Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, a masculine perspective of warring feminine identities in a hotbed of perversity. Lesbian critiques often compare Petra Von Kant to a long line of exploitational horror tropes, whereby lesbianism is equated with vampirism. But Fassbinder is hardly so reductive. Amidst his textual nudges (Petra writes a letter to someone who just happens to be named Joseph Mankiewicz), there’s much to be said as concerns power dynamics and manipulative tactics of gendered role playing.

It’s no mistake that we focus continually on the multitude of mannequins littered throughout her bedroom, posed in positions we often see the humans imitating. Petra fashions Karin, but her need for intimacy allows Karin to fashion her, the dreadful irony that love is nothing more than a means of control. We see one lone glycerin tear falling down Petra’s porcelain face, herself as ghostly, ethereal, and fake as one of the inanimate objects she hangs her own designs. “You’re all so fake!” she eventually shouts at her distant family members. Just as Petra has heretofore used mirrors and her reflection to address those around her, she’s only shouting back at herself.

Film: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆