In 1948 Greece, peasant woman Eleni (Kate Nelligan) struggles to keep her children out of the clutches of the communist faction intent on terrorizing the mountain village where she lives by forcing the adolescent females to join their brothers in waging war and abducting younger children to be funneled into communist camps inside the Iron Curtain. Eventually shot and killed in front of a firing squad for her rebellion, youngest son Nick (John Malkovich), who had been sent to live in the US with his father, is granted an opportunity to return home through a work assignment from the New York Times to find out exactly why his mother was murdered and who was responsible.

Like many films of its ilk, Eleni suffers from the creators’ wishes to instill the subject matter with impenetrable nobility, the peasant woman of its title embracing the well grooved yoke of saintliness. As portrayed by the talented Kate Nelligan, she’s a fiercely rebellious woman and gives an admirable performance—though she’s never quite believable as a peasant woman, her eye brows painted in thickly but her teeth (and English language dialogue) a constant distractions in her characterization. Staunchly heroic, she’s never allowed to exist in any real terms, and so her actualization suffers from the same broad strokes as many examples of innocent people ravaged by wartime atrocity, like Jonathan Treplitzky’s The Railway Man (2014) or Angelina Jolie’s Unbroken (2015)—films so sterile, their protagonists feel like fabled legends meant only to inspire but never to question.

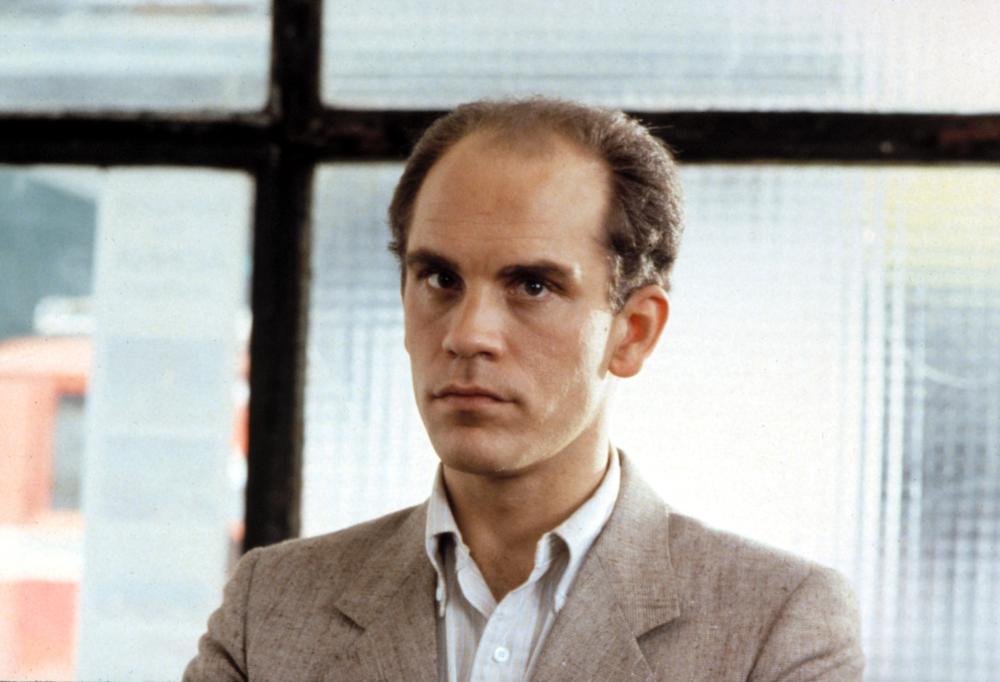

This also neuters the efficacy of Malkovich, seen to anxiously wrestle his demons, which suggests something much more sinister (as he packs a gun for the trip, a wife played by Glenne Headley gets her only notable moment of screen time by expressing concern) in his struggle to search for answers or seek vengeance. Responsible figures from the past are approached, examined, and threatened, but by the time we reach this inevitable point, Yates has strained Eleni through so much noble suffering of its title figure the audience is either calibrated for blood lust or hammered into uncertain apathy.

A lack of English language titles deliberating chapters of contemporary Greek history marks Eleni with a certain significance, and it is reminiscent of a more genre oriented piece several decades later, Tony Krawitz’s 2012 title Dead Europe, wherein a son returns to the homeland to scatter his father’s ashes only to discover a curse hangs over the family name there. However, this examination grapples with how murky elements of the past continue to consume ideas regarding the present, details supposedly informing the anxiety of its protagonist. Eleni is bolstered with fine performances from fine actors (some of them wholly unnecessary, like a post-Oscar winning appearance from Linda Hunt), but it is never freed from its overdetermined presentation.

Disc Review:

Kino Lorber releases the title under its Studio Classics label in 1.85:1. Picture and sound quality are superior, particularly in the rendering of on-location shots from DP Billy Williams (the thrice Oscar nominated cinematographer was fresh off his win for 1982’s Gandhi), while Yates employed composer Bruce Smeaton (a choice collaborator of Fred Schepisi during the 1980s) for a score unable to replace the film’s lack of historical or emotional finesse. No extra features are included on the release.

Final Thoughts:

Worthy of a look for the performances of Malkovich and Nelligan (an actor whose name in the credits should always command attention), Eleni fails to rightly capture the significant turmoil wreaked by Communism on Greece during the 1940s and 1950s, and may be most notable as a conversation starter on these talking points.

Film Review: ★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆