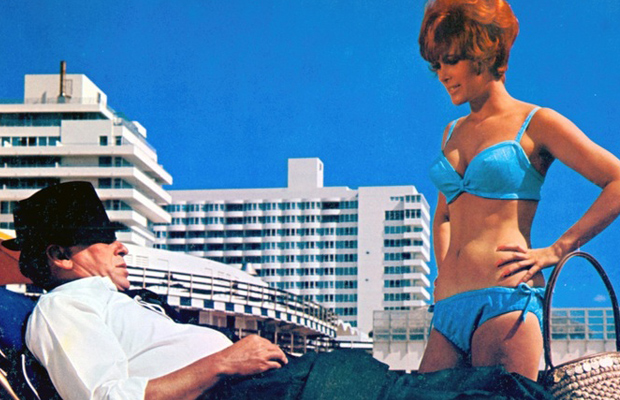

In Tony Rome, Sinatra plays a Humphrey Bogart type private investigator who gets wrapped up in a wealthy family’s dirty laundry. Retrieving a hung over heiress (a wasted Sue Lyon) for her worried father, Rome is hired to find out what exactly happened to her missing diamond pin following a night of heavy drinking. Distracted slightly by a flirtation with a woman who was at the party (Jill St. John), Rome figures there’s something funny going on with the girl’s stepmother (Gena Rowlands). Richard Conte stars as the straight shooting homicide detective who cleans up Rome’s legal woes so the investigation can take place.

In 1968’s sequel Lady in Cement, Tony Rome locates a drowned blonde woman on the ocean floor while improbably searching for sunken pirate treasure. Now, he’s charged with finding out who the woman was, an investigation which begins with looking into where the dead girl worked as a stripper, interviewing her roommate (Lainie Kazan) and catty gay boss (Frank Raiter). The night before she died, the girl attended a glitzy party thrown by Kit Forrest (Raquel Welch), a woman whose associations with some mobsters find Tony Rome quickly in over his head.

Clearly, the stronger of the two titles is the first entry, Tony Rome, wherein Sinatra, despite his multiple sidetracks into wisecracking, seems serious about fashioning his titular PI into a signature role. The film led to one of the strongest films from his late prolific period, 1967’s The Detective, which, whether it was trying to be or not (and isn’t exactly loved by queer theorists recuperating characterizations in the systematically homophobic history of gay representation in Hollywood) is somewhat progressive and certainly ahead of its time in tone and stature.

Douglas maintained a better balance of seriousness with the star’s braggadocio in Tony Rome, which allows for the characterization to feel more comfortable in its seediness. Look no farther than the book end title track by Lee Hazelwood and sung, uncomfortably, by Nancy Sinatra, crooning unenthusiastically about her father’s character as a man who’s always ‘out and about.’ The supporting cast is perhaps more impressive here, most notably a young Gena Rowlands as a trophy wife with a few secrets. Meanwhile, a slight turn from a gone-to-seed Joan Shandlee (you might remember her as a Billy Wilder regular, most famously as the shouting leader of the girl band in 1959’s Some Like it Hot) as a prostitute named Fat Cindy rather succinctly sums about how Sinatra and co. really feel about the usefulness of women (bolstered by its generous ass shots of its actresses, a smarmy in-joke even more abused in the sequel)

Both films feature a convenient love interest for Sinatra’s Rome, beautiful, voluptuous younger women whose tangential involvement isn’t really in synch with the narrative at large. This is particularly true with Jill St. John, stuck doing a comely Tina Louise impression as a red-headed relief for his considerable tension. The latter film has an even more unlikely romance with none other than Raquel Welch, here appearing with an impressive mane of hair (a young Lainie Kazan also notably appears in one sequence as a stripper). The representation of women is even less respectable in Lady in Cement, the coroner describing the titular dead blonde woman in terms of her pelvis. “She never delivered any babies. But she definitely had relations with men,” a lascivious suit explains to Sinatra and a crusty Richard Conte. “She would have made a natural mother,” he concludes. Worse, how the film treats a pair of homosexual characters, one of them coded as bitchy and flamboyant, detracts from some of the sensitivity Gordon and Sinatra managed (perhaps despite themselves) in the earlier The Detective. But beyond these horrific moments of what were once considered acceptable motions of misogyny and homophobia, Lady in Cement just simply isn’t a good film, ruined at nearly every instance by a jaunty score from Hugo Montengero which suggests the film is a humorous comedy instead of a murder mystery.

Disc Review:

Twilight Time presents this limited edition double feature release (3,000 units) in high definition 2.35:1, with 1.0 DTS-HD audio. Picture and sound quality are great on both titles, yet it’s remarkable to note how much the latter title appears dated in comparison with the first, which manages to seem a bit less restricted to a particular moment in the swingin’ 60s. Twilight Time provides isolated track scores as well as audio commentary with film historians Eddy Friedfeld, Anthony Latino, Lee Pfeiffer, and Paul Scrabo.

Final Thoughts:

Author Marvin H. Albert is no Raymond Chandler, and Sinatra doesn’t come close to approximating Bogart’s charisma, but at least in his first outing as Miami PI Tony Rome, a routinely entertaining mystery thriller is assembled.

Tony Rome

Film Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Lady in Cement

Film Review: ★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆