After the drowning of their preadolescent daughter, Christine, in the backyard of their estate, John and Laura Baxter (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie) take off for Venice, where John accepts a job to restore some mosaics in one of the city’s many dilapidated churches. However, once there, the couple is introduced to a pair of strange sisters, Wendy (Clelia Matania) and Heather (Hilary Mason), the latter of whom is blind. An encounter with Laura reveals that Heather can see the spirit of a young dead girl trying to contact the couple, to tell them that while in Venice, John is in danger.

The only significant adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s work post Hitchcock’s trio of memorable titles (Jamaica Inn; Rebecca; The Birds), Roeg adapts from the author’s short story, changing a few significant details that allow for the continual reference to the tragedy that opens his version. The all-encompassing nature of fluids, particularly water and blood, are featured endlessly, both indicative of their life giving properties as well as their ability to either take it away or indicate the passing of it. The continued rain motif, rippling across the surface of the deadly pond, skating across car windows, is equated with broken and breaking glass, happening several times within the film. Water across a transparent slide in the opening segment morphs a red streak into a sickle shape that figures into the film significantly, a symbol that a spiritual world seems to use as means to communicate (unsuccessfully) with Sutherland’s John. Each use is a clue, a mosaic of a shattered message being puzzled back together like the reconstructions of the mosaics John is working on.

Water takes the life of poor Christine, dressed in that shiny red raincoat (called a ‘mac’), a color that figures heavily in the film’s visual tapestry. From Christie’s posh boots, to a scarf, to the hooded figure scampering around the deserted Venice streets, and even the hair of the unnerving psychic, Heather, it’s a vibrant flourish that announces the continued coincidence of Roeg’s film. The interconnectedness is purposeful, hinting that the Baxter’s have been fated to languish in Venice, a city of waterways. Of course, the locale strongly recalls Visconti’s adaptation of the Thomas Mann novel, Death in Venice, in which a plague slowly overtakes the population. There’s something afoot going on here as well, the warning sign ‘Peril in Venice’ prominently in English on the side of the church John’s team is stationed within. Its unfriendly embrace of English speakers recalls the trio of Brits plus Christopher Walken struggling through Paul Schrader’s nightmarish The Comfort of Strangers (1991). It is easy to get lost in the labyrinthine streets of the dank, watery city.

Religion is constantly referenced, but rather as the incorrect key for the otherworldly. The streaked slide from the film’s opening shows the red hooded figure in a church pew, and, of course, Sutherland’s character is responsible for reconstructing these dilapidated artworks housed in these places of worship. Bishop Barbarrigo (played with a strange air of mystique by Massimo Serato, supporting player in a number of Euro sleaze productions, like Giulio Berruti’s Killer Nun) seems equally unenthused. “The churches belong to God, but he doesn’t seem to care about them,” he sniffs. Christie’s grieving mother isn’t religious, but seems open to believing in the spiritual realm. When asked if she’s Christian, she responds that she likes children and animals. Yet, she remains the conduit that stays connected to the psychic sisters, Heather and Wendy, truly on the more unnerving end of cinema’s legion of psychics, perhaps because Roeg keeps trying to subconsciously connote that we shouldn’t take their eagerness to help the mourning couple at face value. Sutherland’s character, on the other hand, supposedly has psychic abilities that his intellect has blinded him to. He is staunchly opposed to anything religious, though he is entrenched in the church and is often evoking Jesus Christ as his chosen pet profanity. Rather than listen to his intuition, it is his intellect that forces him blindly to his fate. Roeg taps into the same vein as Sophocles, but like Oedipus in reverse, John Baxter is already blind.

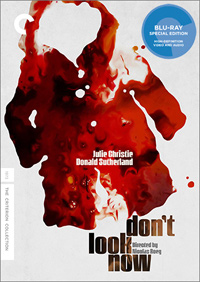

Disc Review

Even with its 4K digital restoration, the layered and sometimes painterly grain of several sequences has been left intact. In the film’s extra features, several of which include sequences from the film, the quality of the restoration is immediately apparent by comparison, all the dank, dreary sequences in Venice alive with brooding menace. Presented in 1.85:1 aspect ratio, Anthony Richmond’s superb cinematography (for which he won a BAFTA) is not to be missed. A handful of winning extra features are also all well worth a look.

Don’t Look Now…Looking Back:

A twenty minute feature from Blue Underground in 2002 features Roeg, Richmond, and Editor Graeme Clifford, who relates that Roeg considered the title to be his ‘exercise in film grammar.’

Death in Venice:

A seventeen minute interview with composer Pino Donaggio reveals how he became involved with the project, which was sort of accidental, but would set Donaggio off on a career path that would eventually see him become a regular collaborator with Brian De Palma. Interview is also from Blue Underground and from 2006.

Something Interesting:

About half an hour’s worth of interview footage from co-screenwriter Allan Scott, Richmond, Christie and Sutherland is assembled, each speaking of their involvement with the film. Scott reveals that two other directors were originally attached, including Larry Peerce.

Nicolas Roeg: The Enigma of Film:

About fifteen minutes, this segment features directors Danny Boyle and Steven Soderbergh, each speaking about how Roeg influenced their careers. Boyle has interesting commentary about Roeg’s predilection for zoom lenses, something most ‘proper’ directors never use.

Clifford/Roeg Interview:

An interview from November, 2014, conducted by writer/historian Bobbie O’Steen, revisits specific aspects of the film with Editor Graeme Clifford and Roeg. Feature is quite in-depth from their perspectives, and runs nearly 45 minutes.

Roeg at Cine Lumiere:

A 2003 Q+A with Roeg following a screening of Don’t Look Now at London’s Cine Lumiere finds the director discussing his focus on visual aspects of filmmaking rather than dialogue, and how our minds engage with the world in non-linear fashion (daydreams, fantasies, nightmares) in much the same way he wished to craft his cinematic endeavors.

Final Thoughts

Roeg’s film announces itself as a provocative command. “Don’t look now,” Sutherland tells Christie upon observing the two women eyeing them in the Venetian restaurant. Likewise, it indicates that there’s a right and wrong time to engage in the act of seeing. As the film closes, we understand that a major character has been seeing things (as have we) in improper sequences. Likewise, the notion of ‘second sight’ heightens the sense (or perhaps, the tense) of seeing—something that can be done as past, present, or future. Early on, in the film’s opening on that early Sunday afternoon in the home of the Baxter’s, we focus on the title of a book next to Christie on the couch (just as she’s looking up how to answer their precocious daughter’s question about why frozen water appears flat even though the earth is round—she must find the answer to ‘shatter’ the surface and break into the explanation) titled “Beyond the Fragile Geometry of Space.” This is exactly where Don’t Look Now resides, a wonderfully compelling, incredibly astounding masterpiece from Nicolas Roeg, which yields new surprises with each successive viewing.

Film: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆