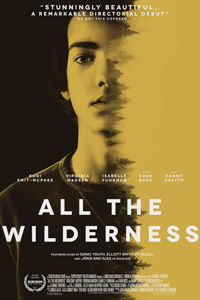

Wild at Heart: Johnson’s Solipsistic, Sincere Coming-of-Age Drama

After witnessing his father commit suicide, his teenage son, James Charm (Kodi Smit-McPhee) has difficulty coming to terms with it, and he begins to have a morbid fascination with death, keeping a journal where he documents all the dead things around him by sketching them while also recording the cause of death. His mother, Abigail (Virginia Madsen) is alarmed at this, and when James advises a bully at school of his upcoming ‘death date,’ this instigates a trip to a nonchalant therapist (Danny DeVito). At the therapist’s office, while reading aloud the poetry of Carl Sandburg, James meets Val (Isabelle Fuhrman), who he finds himself attracted to. In an effort to escape the confines of his home, James sneaks out at night, bringing him into contact with a musician, Harmon (Evan Ross), who is squatting in an old warehouse and seemingly living a carefree life. As James follows Harmon, he runs into the food truck where Val works, and soon he finds himself returning to the same location to pursue her.

Not only is James’ narrative exasperating in its conventionality (despite the surname that sounds like something out of Hal Hartley film), but Johnson’s casting doesn’t help. Despite a laudable performance, Smit-McPhee seems to be the go-to teen for troubled, bookish youths, as this is similar to his recent stints in fare like 2014’s A Birder’s Guide to Everything (broken homes and nature as motifs), or even 2010’s Let Me In. Supporting characters are like bright shiny toys meant to serve specific purposes, such as the gravelly voiced Ross (son of Diana, who stands out a bit more than usual), while Isabelle Fuhrman’s love interest is underwhelmingly handled.

Notable adult actors could have been used more expressively, such as Virginia Madsen’s pained mother, or Danny DeVito’s intriguing therapist. The morbidity which colors the opening frames of James Charm’s narrative dissipates quickly, as we switch gears and it becomes another tale of lovelorn teen angst as a means to escape the emotional torpor of tragic circumstances. At the same time, this relegates the film’s sincerest strengths to a peripheral, insubstantial emotional peripheral zone.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆