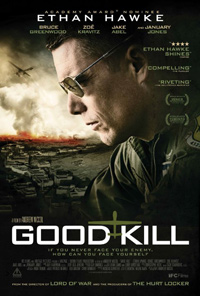

Fatal Irony: Is There Anything Good About This Kill?

Niccol, a director that’s made a career out of dissecting the fundamental ideals of socio-cultural trends and examining their inherent, fatal flaws, is again using the medium as a sounding board for social discussion. Having recently assessed the more oblique, ideological nature of the one-percent ethos (In Time) and the resurgence of Communist values (The Host), he’s shifted his focus to a far more tangible pop culture topic by digging his teeth into the implications of drone piloting.

His protagonist—Major Thomas Egan (Hawke)—is a conflicted family man grappling with the nature of shifting from active conflict to a safer, more passive and technical, role. In theory, the ability to fight for his country from the safety of a glorified portable in the Las Vegas desert, merely a few blocks from his family who he can go home to every night, should be ideal. But something about the lack of risk and the sense of emasculation stemming from attacking an enemy with only a joystick and some buttons brings out an intense sense of self-loathing.

His wife (January Jones) notices his emotional absence, advertising her sexuality in an effort to regain his attention, while his new co-pilot, Vera Suarez (Zoe Kravitz), finds his aloofness appealing. She also identifies with his sense of unease, having a decidedly liberal perspective on the nature of drone piloting, responding with frustration and awe to orders that put civilians within the borders of explosions.

These divides and broad character strokes—with Suarez representing the idealistic voice and other co-pilots having aggressively conservative perspectives on the subject—are most of what makes Good Kill feel a tad righteous. Their discussions, though valid within the lexicon of what their work entails, play like a PowerPoint checklist of points to ensure both sides of the debate are clearly spoken for. It also doesn’t help that the introduction of the CIA as an omniscient, irresponsible villain, forcing these pilots to bomb compounds filled with women and children, exist only to escalate the moral ambiguity of the situations and the overriding character arcs. These characters aren’t real people so much as ciphers to force an aggressive and persisting discussion on the central topic.

Contrarily, Niccol’s handling of the drone sequences, wherein pilots in a tiny room blow up buildings from across the world, are developed with a palpable sense of tension and a natural emotional progression that ensures the topic goes from black and white to an increasingly muddied grey. He also raises some clever ethical points by injecting an unlikely narrative trajectory involving a serial rapist in Afghanistan that the pilots watch powerlessly from afar, later blowing up a building believed to house a known terrorist that just happens to be adjacent some children playing in the street. The sense of unease that stems from these situations is highly effective and does successfully sustain the narrative drive for the duration of the runtime.

It’s just unfortunate that the other peripheral story elements are so clunky and contrived. To be fair, Niccol’s dialogue isn’t exactly stilted or problematic. In fact, the scenes of conflict are quite plausible, aided by strong performances all around—even from January Jones, which is quick shocking in itself—but there’s never any sense of human nuance amidst characters that all seem like puppets in a film that exists to make a political point. No matter how often Egan speeds around in his car, running red lights while drinking hard liquor, and no matter how much his wife broods around the house trying to get him out of his shell, there’s no greater sense of an actual relationship and no real hint at what might have made it work years prior.

There’s also a strange, unintentional irony within the text in the form of sexism. Hawke’s character is inherently a bit of a cliché. He’s a tortured military man living within the vacuum of a self-imposed existential crisis, carrying the weight of the world and his role on global peacekeeping on his shoulders perpetually. The women around him exist merely as sexualized caretakers, representing a maternal perspective on domesticity and global politics, while trying to soothe our conflicted protagonist with sex. Sadly, that’s really all these women are allowed to offer within the world of Good Kill, acting as representations of the temptations and failures of the man this story focuses on.

Still, despite these glaring flaws, everything about this bit of topical entertainment works quite effectively. The production package is polished and Niccol has a natural ability to build an emotional and cerebral arc simultaneously, making the climax quite powerful for what it is. As such, there’s an initial, fleeting feeling of having witnessed something vital and substantial ones the end credits pop up. It’s just a shame that closer scrutiny reveals just how manipulative and somewhat smug it all is.

Reviewed on September 9th at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival – Special Presentations Programme. 105 Minutes

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆