Desert Fury: Sen Gets Bleak in the Heat of a Cold Case Mystery

Strangely, it plays like the inverse, in many ways, of his most well-traveled title, 2013’s Mystery Road, where an Indigenous detective is trying to solve a young girl’s murder in the Australian outback. He returns to the same zone of interest with a similar narrative thrust, except this time the detective is a grizzled, white man idly trying to dig up clues about a twenty year old case of a missing Aboriginal girl whilst nursing his heroin addiction. All the color has been drained from this bleak horizon littered with splintered humans who were greatly affected by the ripple effects of her disappearance. Sen’s ambience is captivating, and it’s a formidably crafted film in which he himself served as director, screenwriter, editor, composer, casting director, and cinematographer.

Detective Travis Hurley (Simon Baker) arrives in the small town of Limbo, a dusty speck of a place barely surviving due to the depleted opal mines which keeps the locals digging feebly into the earth. He’s looking for a man named Charlie Hayes (Rob Collins) to question him about the disappearance of his sister Charlotte twenty years prior. Travis has been tasked with determining if there’s any new evidence which would allow this cold case to be reopened. He’s not interested in finding Charlotte, just poking around to see if anything obvious has surfaced in the last two decades. Charlie’s not interested in talking, and neither is his sister Emma (Natasha Wanganeen). Just as Travis is about to leave his rock formation lodging, Limbo Hotel, his car is tampered with, requiring him to stay an additional week until the replacement part arrives. And suddenly, both Charlie and Emma separately begin to correspond with Travis, and it appears the townsfolk know more about what happened than was ever divulged (or properly recorded) by the police.

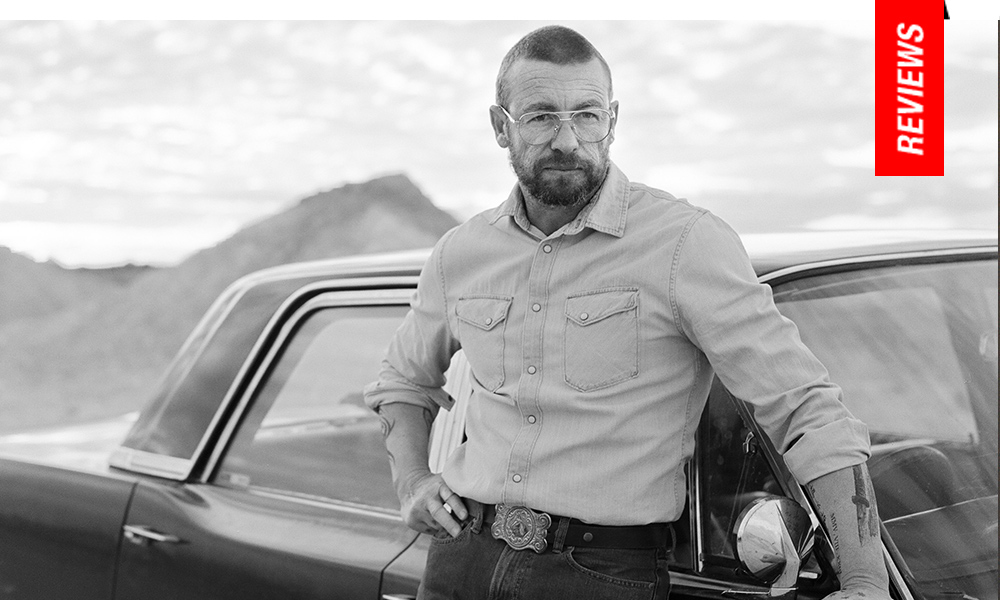

We’ve never seen Simon Baker quite like this before, a cool operator with an indolent gait slowly rolling through town like a disinterested tumbleweed, looking like he could be Walter White’s brother from Breaking Bad. There’s evidence of his humanity, still, though he’s been reduced to something of a shell of man. You could say he’s stoic, but depleted is more apt. The few remnants of misery surrounding Charlotte’s disappearance are all that’s left to define the town, it would seem. Egregiously racist white cops spent more time terrorizing some random Indigenous men and then her broken spirited brother before bungling the likely candidate, a white man who had an opal mine where he’d sedate young Black girls at parties to satisfy his sexual needs. He conveniently died a year ago, his dusty brother tight lipped on the exact details.

All Travis needs is to unearth some new evidence for the case to be reopened, but the only folks who can help are Charlotte’s brother and sister, leery about the police, especially white ones. But there’s something about the world weary Travis which motivates both Charlie and Emma to open up to him—perhaps because they sense he’s equally as broken. Rob Collins and Natasha Wanganeen end up providing the emotional backbone of the film in ways Barker’s Travis cannot, and when it’s evident they’ve become invested in the possibility of some catharsis Limbo really feels unsettling due to the inevitability of justice being denied yet again. The compensation for his ineffectuality perhaps explains why Travis instead tries to assist these siblings, albeit quietly, in reconnecting with each other and Charlie’s children. And perhaps it’s because he’d really like someone to be a similar go-between with his own estranged child.

Despite its lethargic momentum, which fits the stagnation of all these characters who are all metaphorically caught in their own state of limbo, Sen’s film often feels hypnotically sinister. From the intriguing looking Limbo Motel, which is fashioned to look like a subterranean rock cavern, to the mining caves yawned open to spill dark secrets, and the bird’s eye shots of the striking Opal Mountains, it’s a landscape which feels beautifully primordial underneath the gaze of a cold, glaring sun. Sen’s cinematography is a star unto itself, keeping us at an admiring distance, much like his protagonist holds everyone at an arm’s length he barely has the strength to maintain.

Reviewed on February 23rd at the 2023 Berlin International Film Festival – Competition. 108 mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆