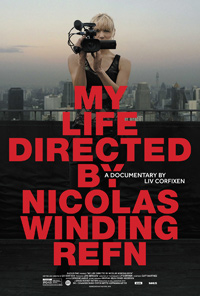

Portrait of an Artist: Corfixen’s Familial Doc an Interesting Conversation Piece

As many an auteur before him has experienced, the title that often follows one of towering acclaim will end up being treated with derision, and we should fully expect to see Only God Forgives recuperated, in some sense, as an unsung gem from Refn’s filmography in decades to come. But Corfixen’s documentary isn’t meant to profess an opinion about her husband’s film, but rather the psychic discord of creating something you want versus what a wayward, fair weather audience demands. The result is compelling, if ultimately messy and sometimes uncomfortable, as if we’re seeing the vulnerable soft flesh of a crustacean that’s been shriveled out of its elaborate shell.

When on set and in front of the press, Refn exudes a confident game face, yet Corfixen shows an artist struggling to overcome mounting desperation. In the middle of production Refn breaks down, unsure of what it is that he’s even trying to say with this film. Like a cornered animal he barks at his wife after seeing the first cut, denouncing the film as a failure. Then, after the mixed response at Cannes, he comments that the film is a success, something that such a divisive reception inevitably means.

Alejandro Jodorowsky, an enigmatic specter (Refn dedicated the film to him) opens the documentary, sharing his wisdom with Refn, who seeks advice. Later in the film, Corfixen speaks with Jodorowsky by herself. He breaks out his tarot cards in an effort to assuage the obvious frustration she’s experiencing with her husband, whose career has forced her to pause her own as she cares for their children. Such intimacy lends the film certain unkempt pith, with Corfixen often rattled at being locked out of production meetings during the shoot, though we’re unsure if this is to keep certain elements from being recorded or due to her relationship with Refn.

On the other hand, Corfixen gets unprecedented access to Refn in his most private moments, and one wonders if such vulnerability would have been possible with a more objective filmmaker at the helm. He seems to have a predilection for reading those that damn him, quoting freely from an online piece that seems less constructive than it does a hollow piece of hateful criticism that says more about the critic than it does Only God Forgives.

At a mere sixty minute running time, Corfixen’s doc is neither in defense or damnation of her filmmaker husband. Too uncomfortable to be a mere bonus feature and too slight to feel relevant outside of those curious about Refn, perhaps it will just represent a stepping stone for Corfixen as she reclaims her own creative endeavors.