Woman Thou Art Loosed: Des Pallieres Disorientates with Fractured Character Portrait

Between constantly shifting time periods and abrupt transitions from one clutch of characters to the next, a roughhewn composite eventually begins to take form in Orphan, the latest film from French auteur Arnaud des Pallieres. It’s a notable departure from his last effort, historical drama Age of Uprising: The Legend of Michel Kolhaas, the most recent in a fine tradition of adaptations of the source novel by Heinrich von Kleist. Again working with screenwriter Christelle Berthevas, the director hearkens back to the more experimental narratives of his earlier career in this tragedy of a woman who’s clearly the product of an abusive environment who engages desperate measures for the chance at a better life. The central character is portrayed by four different actresses from integral chapters of the character’s life, a central conceit more interesting than it is always effective, but playfully addresses notions of identity as the ability to slough off one for another when circumstances allow.

Renee (Adele Haenel) is a no-nonsense headmistress at a provincial school, trying to get pregnant by her beau (Jalil Lespert). When Tara (Gemma Arterton) is released from prison, she seeks out Renee for retribution concerning a past deed Renee owes her for, turning a comfortable existence upside down. Meanwhile, Sandra (Adele Excharpoulos) responds to a personal ad for Lev (Robert Hunger-Buhler), an older gentleman wishing to adopt a daughter and who makes money off of gambling at the horse races. Meanwhile, thirteen year old Karine (Solene Rigot) struggles with being abused by her father (Nicolas Duvauchelle) and having sex with older men at a nearby nightclub she frequents. And then young child Kiki (Vega Cuzytek) is tasked with helping search for two young neighbor children who have disappeared suddenly, an incident which causes other significant rifts. But as we learn, all four women are Renee from different times and different places.

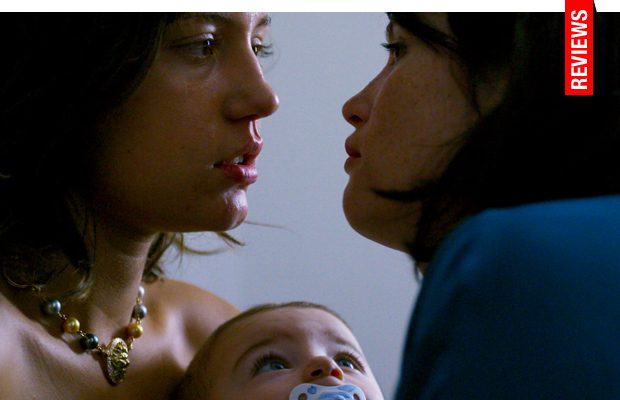

Alternate performers playing the same character is nothing new, whether in a more contained, classical form such as Bunuel’s The Obscure Object of Desire (1977) or Todd Haynes’ equally solipsistic I’m Not There (2007). To the film’s detriment is a curious visual design from DP Yves Cape (Holy Motors; White Material), who composes his frames almost completely and indefinitely with extreme close-ups. While this brings us into sharp focus on whoever we’re currently focused on, whether it be Renee, Sandra, Karine, or Kiki, it also has the same effect of punctuating all of one’s sentences with exclamation points—after a while, this only assists in losing its commanding effect. Likewise, the different temperaments between performers, particularly the poutiness of Adele Excharpoulous and the composed confidence of Adele Haenel, sometimes feels a bit distracting, at least enough to jar us out of our contemplation of the tragedy which transitioned Sandra to Renee, and took down Gemma Arterton’s bitter bad girl Tara with her.

Also running through the film is an uncomfortable fixation on damaged father figures, men who either beat (Duvauchelle), prey (Hunger-Buhler), or prime (Lopez) the young woman for their own particular uses, whether she’s fulfilling notions of daughter, pseudo-daughter, or pet. By the time we get around to exploring Jalil Lespert as Renee’s husband, we’re as wary as she is, sure her interests are not his top priority. The trouble with jumbling all these tangents together is the film’s inability to give a comprehensive portrait of any of Renee’s approximations, which makes moments featuring significant physical trauma seem exploitational.

Meanwhile, sex scenes with the woman’s older lovers (particularly in exchanges featuring Excharpoulos) are particularly uncomfortable, portraying a woman who’s depicted as having agency but has clearly found a way to get what she wants by giving men what they want, making the best of her reactive stance. Of course, this is potentially the underlying issue des Pallieres wishes to address, but only succeeds in smearing and searing our faces into Sandra’s sexual interactions. More interesting is the clearly sexual relationship shared by Tara and Sandra, but also never manages to register as more than a tawdry flourish.

As the aggravated, jagged edges of this troubled woman’s life finally fuse together for the audience, Orphan, referring to her chosen state of mind since all those kind to her had ulterior motives, loses its viability to properly galvanize us. And while she may find herself to be at a certain precipice by the finale, (at an impasse the audience already predicted for her as it was simply a matter of reaching the inevitable) we don’t care in which direction she takes the plunge.

★★½/☆☆

Reviewed on September 12 at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival – Special Presentations Programme. 111 Minutes.