Only This and Nothing More: Kempff Explores Cultural Gaslighting in Parochial Thriller

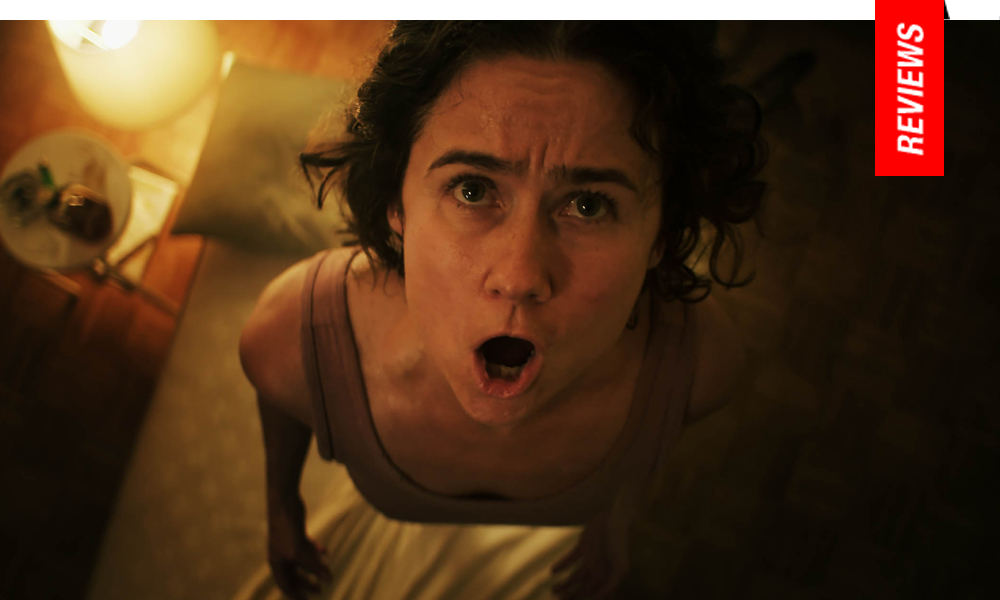

An insular exercise of how the cultural stigma of mental illness creates a glaring pathway of socially acceptable forms of gaslighting, the success of such an exercise is dependent on the well-executed lead performance of Cecilia Milocco, who is equally sympathetic and frustrating as a woman whose faculties are also questioned by an audience conditioned into dismissiveness.

Molly (Milocco) has recently been released from an institution after having survived a traumatic event. Though the exact nature of what transpired is never clear, she’s fixated upon a woman, assumedly a romantic partner, and her memories of what seems their last day together. Released on her own recognizance, Molly moves into a new apartment building and almost immediately begins to hear a knocking from her ceiling, and eventually accompanying cries from a woman. Consulting her upstairs neighbors, she believes the noises she’s hearing justify calling the police…several times and on several neighbors. In due time, a confrontation threatens to land her back in the same institution, until she finds another way to prove what she’s hearing is real.

Back in 1972, feminist psychologist Phyllis Chesler penned Women and Madness, a landmark expose on the negative impacts of psychology and psychiatry on women due to the saturation and domination of men in both these fields and their determining force in the heteropatriarchy. It was also a period which unleashed the most formidable representations of women in the throes of violent nervous breakdowns, and Kempff’s formulation bears more than passing resemblance to the likes of Catherine Deneuve in Repulsion (1965) or Susannah York in Images (1972).

Curiously, little has changed in our cultural acceptance and understanding of mental illness and varying degrees of intersectionality, and if Chesler was considered part of the second-wave of feminism, it seems we’re still hovering in these same waters today. Such astute examinations of women gone mad, at least the most renowned examples, were helmed by men. Molly’s sexuality somehow allows Knocking to feel more progressive simply for existing on screen, but it shouldn’t. In fact, Kempff pushes such kernels to the periphery, a trauma involving her past lover the assumed cause of her breakdown, the memories haunting her eventually revealed to be quite separate from the new horrors she’s confronted by.

Kempff feeds us metaphorical clues of Molly’s mind frame, from a small bird on her balcony which ‘can’t quite get a grip,’ and a clip of Bergman’s classic psychodrama Persona (1966) playing on the television at the institution (though this would arguably be a distressing film to ponder in such an environment). We’re as immediately suspect of Molly as her new neighbors, and the autumnal hued cinematography from Hannes Krantz and fitting musical cues from Martin Dirkov (who composed scores for the last feature by Ali Abbasi) crafts a world devoid of any real joy or light for anyone stuck there. A sweltering heat wave suggests an extra element of madness, and Molly eventually begins to sound like the working-class version of Barbara Stanwyck in Sorry, Wrong Number (1947).

Milocco is fantastic in her insular abilities to channel Molly’s trauma, and even when a situation with her neighbors turns violent, her suspicions of them eventually feels justified – if you observe anyone’s behaviors for too long at such close range, anomalies can justify whatever hypothesis you want them to. Having appeared in Ruben Ostlund’s Involuntary (2008) and Tuva Novotny’s Britt-Marie Was Here (2019), the trials and travails of Molly solidifies the actor as one to pay attention to. Although more of a lean art-house psychodrama than a traditional horror film, Knocking speaks volumes about the treatment of both women and those defined by a mental illness or episode. Its finale seems almost truncated, an off-screen conversation confirming a revelation – or does it? The ambiguity, and whose perspective you’re choosing to believe allows Knocking to haunt beyond the credits.

Reviewed on January 29th at the (virtual) 2021 Sundance Film Festival – Midnight Program. 78 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆