A Jazzman’s Blues: Gee Strikes the Right Chords in Tender DocudramaE

British filmmaker Grant Gee, heretofore best known as a documentarian of various musical artists, such as the band Radiohead and Joy Division, turns in a stellar narrative feature with Everybody Digs Bill Evans. For those unfamiliar with the subject, jazz pianist Bill Evans (and the eponymous album), the film serves as a formidable recuperation, while jazzophiles should find this a dour, respectable homage. Anders Danielsen Lie, muse of Norwegian auteur Joachim Trier, gives an exceptionally internalized performance as Evans, reflecting a transitional period in the musician’s life in 1961 following the tragic death of his bassist, Scott LaFaro. What emerges is a quiet study of bruised masculinity, and all the self-medicating used to numb the pain for those trapped by their talent and those chasing whispers of it.

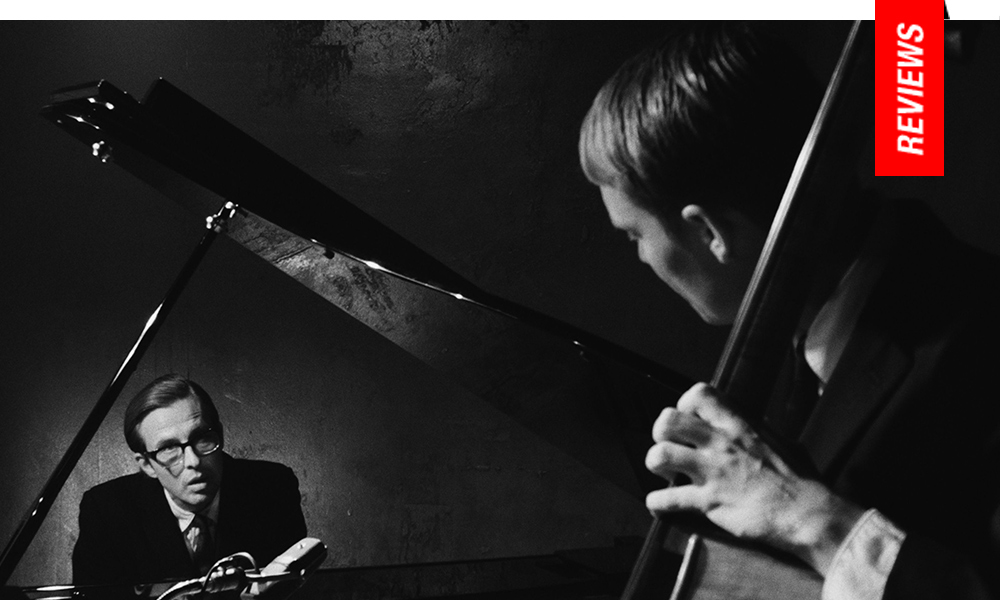

In June of 1961, Bill Evans (Lie) led his prominent trio, consisting of bassist Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian, in a performance at New York’s Village Vanguard. The session was recorded, and by the end of that year would be turned into two prominent albums, which would both be considered amongst the most renowned jazz records of all time. However, LaFaro, with whom Evans shared a symbiotic artistic relationship, died in a car accident only ten days after the performance. Convinced he cannot go on, Evans is on the precipice of losing himself to his heroin addiction, shared with his girlfriend, troubled waitress Ellaine Schultz (Valene Kane). Conveniently, she’s scheduled to visit her sister in Connecticut in a desperate bid to get sober, while Bill’s brother Harry Jr. (Barry Ward) allows him to crash with his family in the city. Evans’ drug issues prove to be too much for Harry, who has considerable demons of his own, and so he’s shipped down to Florida to stay with his droll parents, Mary and Harry Evans Sr. (Laurie Metcalf and Bill Pullman).

The bulk of the film takes place across two extended sequences with Evans first visiting his brother and sister-in-law and then, due to his issues, a stint with his parents in Florida, where he dries out. In both settings he becomes privy to the emotional baggage defining his brother and father, mostly serving as a silent witness to their own unprocessed thoughts. The 1961 period is shot by DP Piers McGrail in stern, shadowy black and white, capturing a dried out carcass of memories. But it’s the women who serve as communicative bridges, and Laurie Metcalf (who recently embodied a polar opposite matriarch as Ed Gein’s mother) proves to be a scene stealer, squabbling alongside Bill Pullman as a couple who’ve weathered period specific storms. Valene Kane, starring as Evans’ long term partner and enabler, is a beautiful, fragile bird, her visage constantly on the verge of blurring into a wounded expression. Gee briefly transports us to color soaked moments in the 1970s, after Evans has moved on, where Ellaine’s own desperate end allows for one of the film’s choice visual flourishes.

From a distance, Everybody Digs Bill Evans is a quiet film about a talented artist, and may sound unremarkable. But much like Richard Linklater’s Blue Moon (2025), it’s a subtle film about an artist’s potential point of no return, and sometimes the ability to move forward isn’t possible. Adapted from the novel Intermission by Owen Martell, Mary Evans makes use of the reference because sometimes ‘the intermission is part of the music.’ It’s a film of impressions, moulding the sometimes cliched struggles of artistic ambition and turning broken hearts into art. In the end, you really will dig Bill Evans if you don’t already.

Reviewed on February 13th at the 2026 Berlin International Film Festival (76th edition) – Main Competition. 102 mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆