Immigrant Song: Kursietis Explores a Modern Slave Trade in Sophomore Film

Opening on the fumes of a childhood fable, we meet Oleg (Valentin Novopolskij), a young Latvian man, landing in Brussels on a rickety plane. A Russian speaker, Oleg’s language barrier immediately places him at odds in the city, where he has flown to work as a butcher in a meat industrial packing plant near Ghent. A fraught interaction with his Polish co-worker Krzysztof (Adam Szyskowski) over the latter being drunk at work ends in the elder man losing his finger and blaming it on Oleg, who immediately loses his job. However, the stipulation for his entrance into Belgium was to work expressly for this packing plant, which makes him vulnerable to nefarious individuals. At first he seems to stumble into a lucky situation when he meets friendly Pole Andrzej (Dawid Ogrodnik) and his affable girlfriend Margosa (Anna Prochniak), who confirm they can find him employment outside of the packing plant. Andrzej offers him a room of his own in a community-house setting where pancakes are served daily and video games are played in the shared living space during off-hours. If this seems too good to be true, it is, with several red flags Oleg ignores (such as Krzysztof also residing in this working class wonderland), and after two weeks on a construction site without pay, Oleg absconds. But circumstances lead him back to Andrzej, who isn’t quite as polite upon the prodigal’s return.

Latvia gained independence in 1991, which saw a small proliferation of new film artists throughout the 1990s. Kursietis, whose 2014 debut Modris was the country’s submission for Best Foreign Language Film (only the seventh of ten such titles to have this distinction), presents a familiar but cohesive portrait of a stranger in a strange land. A notable difference here is the use of a male protagonist, as many portraits of cinematic miserabilism abound of women trapped in foreign countries, often sold into sex trades or equally degrading and unseemly measures of survival.

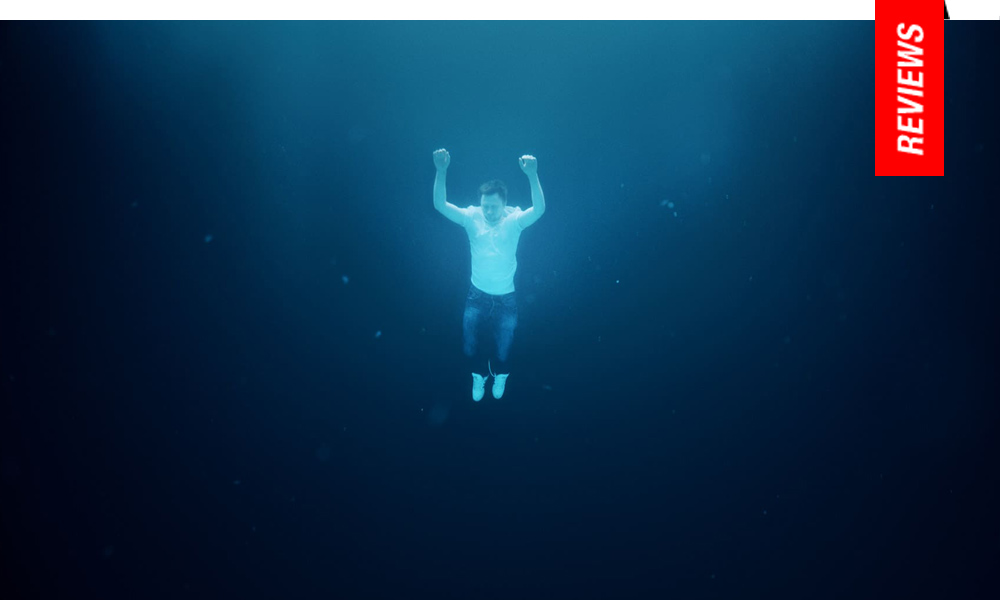

As Oleg, Lithuania’s Valentin Novopolskij gives a sensitive, moderated performance as a man desperate to keep his head above water. Kursietis uses several imaginary asides whereby Oleg imagines himself drowning (which is also eventually used as a baptismal opportunity for rebirth), used infrequently enough to allow a textured change-of-pace from the Oleg’s roaming around Brussels for sanctuary. Between these asides, his journey isn’t unlike early portraits from the Dardenne Bros.’ filmography.

Novopolskij dips into several moments of anguish upon his initial descent, but the film presents a scenario where a breakdown isn’t feasible as far as survival, lending it a sense of neo-realism. Random encounters and conversations reveal Oleg’s ignorance (such as a more obvious exchange concerning Brexit and various countries relationships with the EU). His initial position as a butcher could well be a metaphor, as digging around in the dead carcasses of Europe eventually leads Oleg to despair, unable to send money home to his grandmother following the unfortunate circumstances which force him to lose this job and eventually lands him into a contemporary slave trade under the manipulative hands of a Polish criminal (whose behaviors allow for a snapshot of the different trials afforded women in these situations based on how he treats his girlfriend).

Law enforcement becomes another dual motif, first as a careless exchange where Oleg tries to get himself arrested as a means to escape Andrzej, and then as a potential scapegoat once again, save for a minor detail of saving grace—neither encounter presents a beneficial option for his survival in Brussels. And the upper echelons of Belgian culture allows for the film’s most potent moment when Oleg crashes a private event celebrating a theater troupe, where his sexual encounter with Guna Zarina’s Zita, a theater groupie, ends bitterly. Although Oleg presents a familiar scenario and avoids melodramatic tactics, it’s difficult to imagine Kursietis standing out amongst other contemporary Baltic titles, but it’s an often understated offering featuring a fine lead performance.

Reviewed on May 17th at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival – Directors’ Fortnight. 108 Minutes

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆