Up With Dead People: Hoffman’s Debut an Arresting Development

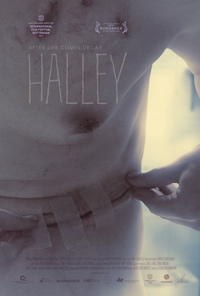

It’s easy to see why long time Carlos Reygadas producer Jaime Romandia (who has also produced for Amat Escalante and Pedro Gonzalez-Rubio) got on board with director Sebastian Hoffman’s exquisite debut, Halley, as it combines the existentialist ennui of Reygadas with Cronenbergian body horror. Hauntingly surreal, and sometimes maddeningly oblique, it never fails to be consistently compelling, and Hoffman’s eerie protagonist manages to resonate long after its final frames.

It’s easy to see why long time Carlos Reygadas producer Jaime Romandia (who has also produced for Amat Escalante and Pedro Gonzalez-Rubio) got on board with director Sebastian Hoffman’s exquisite debut, Halley, as it combines the existentialist ennui of Reygadas with Cronenbergian body horror. Hauntingly surreal, and sometimes maddeningly oblique, it never fails to be consistently compelling, and Hoffman’s eerie protagonist manages to resonate long after its final frames.

Opening with flies coupling in a dirty jar, we follow Beto (Alberto Trujillo), a security guard in a 24 hour Mexico City gym, where his deteriorated physical appearance is in sharp contrast to the pumped up bunnies that frequent the establishment. We soon learn that something is horribly wrong with Beto, and, in fact, he’s actually no longer living. Filling himself with embalming fluid in his apartment, extracting maggots from his decomposing flesh and collecting them in a glass jar, Beto realizes that he doesn’t have much longer before his condition will be obviously apparent. Putting in his final notice with his very friendly boss (Luly Trueba), who, citing her experience with a relative’s cancer, know what it’s like “to be sick,” Beto steps out of his isolation, presumably to retain his final experience of what it’s like to walk among the living. He attends a church service, where that day’s sermon examines the nature of sin and sickness. “Illness and sin are one,” bleats the preacher, convincing those in desperate need of explanation that “faith makes suffering glorious.” Beto is beyond the realm of physical suffering, his vessel crumbling even as he consumes the ignorant, assuaging discourse.

Collapsing in public, Beto is ushered to the morgue, where a detached morgue attendant converses with him after discovering Beto isn’t quite dead. “The diseased become the disease,” says the attendant, eating his cup o’noodles amongst the corpses. Appearing for his last night of work, it turns out the exterminators have come to spray the gym and so Beto’s boss insists that he get a bite to eat with her. She seems oblivious to Beto’s dour attitude, claiming that he has to humor her. “I may never see you again,” she explains. Forcing cheesecake upon him, (“It will make your life sweeter”) and then drinks, the two end up at her place, a situation which becomes increasingly uncomfortable. When the electricity goes out, his drunken boss relates stories about her childhood, and, with a flashlight, has a drunken monologue about her fantasies of Halley’s comet as a child, whose timeline through the universe will eclipse us all. As she passes out, Beto leaves and engages in one last humanly pleasure before leaving for an even more isolated Earthly region.

In mulling over the events of Hoffman’s Halley, one can’t help but be struck at it’s melancholy look at human existence and poetic examination of the possibility of the after life, or lack thereof. Could life be no more than a series of unrelated crossed timelines, where “people suffer in many ways,” and for no apparent reason? It would seem so, if we’re to juxtapose the ideas vocalized in the church service with our protagonist. Of a more curious nature are the references to dolphins, both in the memories related to Beto from his boss, and a painting of a dolphin silhouette in the moon in the morgue. This combination of the cosmic and the aquatic seems relevant, and the dolphin has been historically used to symbolize Jesus Christ in the Christian religion, where previous to the cross, the ‘fish’ was the commonly used symbol. But if we’re all on a predestined journey, where crossed paths are never coincidental, what’s happened to Beto, who seems to have survived his elapsed time? And then there are the flies, born and fed from his still animated frame. An argument for reincarnation, perhaps? Or is Beto aligned with Halley’s comet, a cosmic force glancing past the natural order of life on Earth? Between its grotesque imagery, through provoking existential questions and surreal narrative, Halley is a dispirited reconnaissance of human existence.

Reviewed on January 18 at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival – NEW FRONTIER FILM Programme.

84 Min.