In Dreams: Gan Explores a Century of the Cinematic Syndrome

An audience stares at us through an aperture, as if we’re the ones being observed before various intertitles introduce us to a world where humans no longer dream, as they’ve become ruinous to one’s health. However, there are some beings who still dream, called Fantasmers. And there are those who can perceive these creatures, known as The Big Ones. A beautiful woman (Shu Qi), who appears to exist at the turn of the century, is a perceiver, locating a monstrous Fantasmer who is kept incarcerated, his tears collected and given to wealthy businessmen for their pleasure. The woman abducts the Fantasmer, bringing him to an ornate theater. Once there, he continues to dream and transform. But time passes differently for the perceiver, mere hours correlating to what the Fantasmer experiences as a hundred years.

Following his 2015 debut Kaili Blues and the exceptional Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2018), which is also fascinated with obsessive memories of the past, cineastes have developed a tendency to gush over Bi Gan’s output. Resurrection will be no exception, though its running time will likely court a bit more divisiveness, especially considering a tighter edit might enhance its loopy appeal. But despite it’s arguable ostentatiousness, Gan’s ability to translate cinema as a dreamlike state is certainly exceptional, and there are elements which run along the same wavelengths as David Lynch.

Those hoping for tonal consistency find it impenetrable, especially after a fantastic opening sequence, introducing us to the notion of the Fantasmer and the perceivers. One would be hard pressed to find something more cinematically exceptional than the first thirty minutes of Resurrection, as the breathtaking Shu Qi kidnaps the trapped, flower-eating Fantasmer. Guy Maddin enthusiasts will certainly appreciate the comically bizarre inter titles, such as “Dreaming will make you burn out” as the bedraggled Fantasmer munches on his flora and fauna.

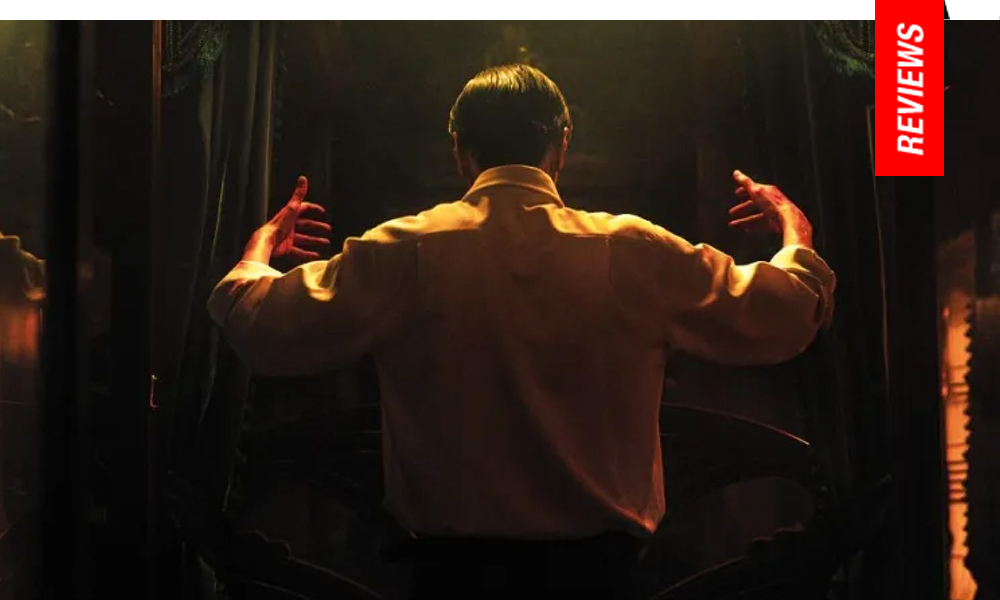

Drenched in German Expressionism, we meet the ‘monster,’ designed like a cross between Nosferatu and Lon Chaney as The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Fritz Lang and Robert Wiene excitingly come to mind before the film switches to a (lightly) queer murder mystery noir, channeling the gonzo energy of Terry Gilliam. The Fantasmer continues to sleep again, then returns as an ex-monk forced to stay overnight in an abandoned temple where he used to work. A voice from a hollowed out Buddha statue directs him to bust out a rotten tooth with a bitter flavored rock. The tooth transforms into an entity who states he is the actual essence of Bittersweet, and on the verge of achieving enlightenment (notably, the form taken is that of the ex-monk’s own father). More time passes, and focus shifts to a drifter and a child who imposes riddles upon him. “What leaves you that you can never get back?” The answer in the film is a fart…but another answer could be time, the passage of which is important considering cinema itself is a mechanism which artificially gives time back to us, but while we’re consuming cinema, also robs us of it.

Then, on New Year’s eve 1999, a vagabond, pursued by something known as the Rainbow Mob, has a chance encounter with a young woman who is a vampire. They fall in love, and she shares her gift of immortality. The Fantasmer returns to his mother’s (Shu Qi) theater from the opening of the film, and she dresses him in the garb of the monster in which we initially met him.

Bits of melting wax and narration provide the segues to these various periods, and much like the contained mobius strip each film is, we end where we began, as glowing human shapes return to sit in the theater, slowly disappearing, having reached a state of nirvana allowing them to transcend to the ether outside of the frame. There’s an inescapable sense of giddiness Gan achieves in the opening and closing segments, our own time melting away like the wax. And while the film’s energies wane as it drifts between these different cinematic textures, Resurrection delivers what feels like six distinctive kinds of cinema.

It’s a phantasmal homage to the art form, and yet it’s also an achingly oppressive assessment on our inevitable permutations as time goes by. Strangely, Resurrection balances these sentiments, as dreaming (and its tangible construct, cinema) takes away time in exchange for escapism or enlightenment. As in Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, “Time comes stealing on by night and day” while we flourish, degrade, and disappear.

Reviewed on May 22nd at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival (78th edition) – Competition. 160 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆