A Boy’s Best Friend is His Mother: Boulifa Explores Complex Symbiosis in Mother-Son Drama

While there are plenty of similar narratives navigating dysfunctional familial relationships, Boulifa conjures the kind of energetic mixture of a more daring cinematic period allowing for characters whose authentic rendering included unlikeable, inescapable realities. It’s a sorrowful film about surviving in a world more interested in failure than success for the nonconforming, but it’s also filled with a respect and grace for characters stubbornly choosing the road less traveled to find the life they might actually enjoy living.

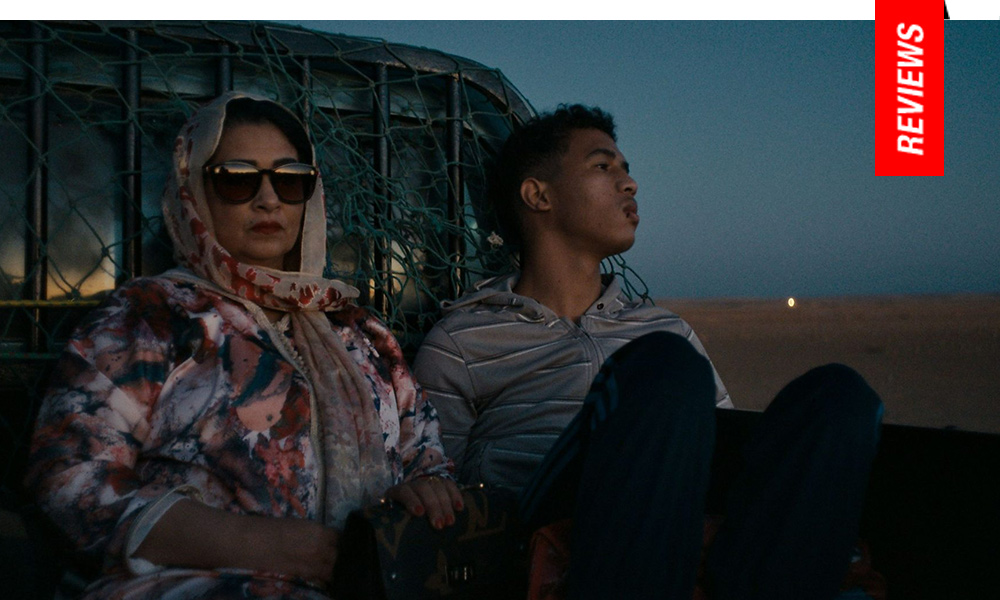

Fatima-Zahra (Aicha Tebbae) has been the black sheep of her family since she was a teenager, where a combination of sexual trauma and strict cultural mores forced her to raise son Selim (Abdellah El Hajjouji) on her own. Together, they have wandered around Morocco in a search for happiness which always seems to be just beyond their grasp. When Fatima-Zahra confirms a looming interview may be the opportunity they’ve been waiting for, it turns out to be a ruse for her rendezvous with a client she believes will save her from sex work, but she ends up with a black eye and her jewelry stolen. Absconding for Tangier, luck is initially on their side thanks to a friendly bus driver who takes a liking to Fatima-Zahra, asking for her hand in marriage as his current wife is dying of cancer. Selim finds work on the construction of an opulent estate being built for Sebastien (Antoine Reinartz), a gay Parisian who seduces the adolescent, unaware of his age or virginity (supposedly). As these new scenarios allow mother and son to drift apart, Selim’s fantasy dissipates at the arrival of Sebastien’s husband (Jonathan Genet), but it seems Fatima-Zahra’s impending marriage has left him without a back-up plan, leading to an act of cruelty.

Compelling in how he examines a fallen woman and her gay son existing within impossible cultural constraints, Boulifa’s script is filled with striking passages and complexity. As Fatima-Zahra, a woman with two names symbolizing a juncture of choice, Aicha Tebbae is perfectly world weary and perhaps aggravatingly naive, forging a path towards the particular stability and comfort she believes possible. “Only God stays the same,” she remarks, eventually compromising for a chance at happiness as a second wife to a man she barely knows. “I’ll be old and ugly soon,” she tells Selim, as clear eyed a reason as any to justify her actions.

In essence, Boulifa has recontextualized Pasolini’s Mamma Roma (1962) for a Muslim woman still using her body to save and secure her son. Whereas once this specific dynamic was the fertilizer for miserabilism or shock value (like Hitchcock’s Psycho, 1960), where taboo soaked up any possibility for characterization, Boulifa has created something painfully human, not unlike the thin line between the poignancy and toxicity of Lorenzo Vigas’ From Afar (read review) as far as the deliberation of how a thwarted intimacy for queer characters can be pushed to jarring extremes.

The narrative switches towards favoring Selim coming of age in the swift realization of his sexuality. Antoine Reinartz steps in as the French Christian whose actions, even subconsciously, are an exploitation of a younger, poor, Arab man who doesn’t initially understand he’s a passing amusement. Echoing a similar scenario in Quinceañera (2005), in which a white gay couple cruelly take advantage of a Latinx youth, there’s a hotbed of intersecting privileges and hierarchies triggered through these relationships. If Selim sabotages his mother, she also essentially abandons him after resigning herself to the only socially acceptable relationship allowed in the confines of religion.

The rigid roles allotted to men and women, Christians and Muslims, backs both of them into a situation where they must separate to survive. If The Damned Don’t Cry is essentially a tragedy, Boulifa also allows for the generous ambiguity of hope, even if they’re doomed to serve as interlopers in any environment either of them dare to call home.

Reviewed on September 7th at the 2022 Venice Film Festival – Giornate degli Autori. Competition. 110 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆