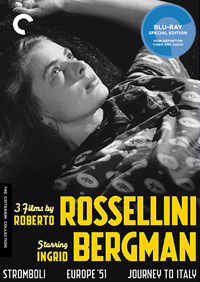

While their scandalous love affair and subsequent marriage eclipsed the five collaborative films they made together, this month Criterion brings Roberto Rossellini’s Ingrid Bergman headlining Voyage trilogy to the collection, comprised of their first three ventures, Stromboli (1950), Europe ’51 (1952) and Journey To Italy (1954). None of these titles would be deemed a commercial success, even while several notable critics and filmmakers would champion them, such as Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer.

While their scandalous love affair and subsequent marriage eclipsed the five collaborative films they made together, this month Criterion brings Roberto Rossellini’s Ingrid Bergman headlining Voyage trilogy to the collection, comprised of their first three ventures, Stromboli (1950), Europe ’51 (1952) and Journey To Italy (1954). None of these titles would be deemed a commercial success, even while several notable critics and filmmakers would champion them, such as Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer.

As their marriage crumbled after three children (one of whom would go on to become famed actress and model Isabella Rossellini), Bergman would eventually overcome the notoriety that had banished her from Hollywood to win two more Academy Awards, while Rossellini would go on to make other acclaimed titles, though the failures of his work with Bergman made it difficult to secure funding. The specter of their scandal (they were both married to others at the time of their affair and Rossellini had also been dating Anna Magnani at the same time) still overshadows this period in both their careers, which is a pity considering the quality of these titles, especially with Journey To Italy, arguably a zenith for both director and star.

An innocent note from Bergman to Rossellini announcing her admiration for his Rome: Open City and a desire to work with him would result in an idea for their first film, 1950’s Stromboli. For years unavailable on DVD, this is the most difficult to appreciate title of the three, a tale of displacement that exudes motifs explored in each of the Voyage films concerning troubles communicating and relating to a foreign culture, relationship crises, class struggles, and notions of faith. Bergman is Karin, a Lithuanian woman that landed herself in a concentration camp during WWII. To escape from the camp at the end of the war, she agrees to marry an Italian soldier, Antonio (Mario Vitale) who has been flirting with her through the barbed wire fence of the camp. “I don’t understand you,” she tells him as they laugh at his broken English, which of course is foreshadowing of what’s to come. Her request to go to Argentina was denied, but her union with fishermen Antonio means she can return with him to his home on the island of Stromboli in the Mediterranean. Immediately, Karin realizes that Stromboli is a trap, denouncing it as a ghost island as soon as she steps ashore. An active volcano on the island constantly threatens to erupt, spewing its ash as profusely as Karin sputters her continual hatred for the dead island where the other women deem her immodest. Her fate seems sealed with a subsequent pregnancy, leading to an eventual epiphany as she ascends the smoky volcano and finally acknowledges a God that will need to lend her the strength to save her unborn child.

Their next film, Europe ’51 is meant to be a companion to another 1950 film from Rossellini, The Flowers of St. Francis, though this time from a female point of view. The surprising suicide of her preadolescent son sends socialite Irene Girard, wife of Ambassador George (Alexander Knox) into a tailspin. In her search for meaning, she becomes a staunch humanitarian, horrified at the living conditions of Italy’s lower classes, attaching herself to a single mother of six (Giulietta Marina), working a shift in an assembly line in a factory, which she asserts is being like “the slave of some evil god.” Eventually, her husband and mother question her sanity.

And with the most powerful film in the collection comes Journey to Italy, considered to be one of the first modern films and one of the most influential of the postwar era. An English couple (Bergman and George Sanders) take a trip to the countryside near Naples to sell some property they’ve inherited. After eight years of marriage, they realize they’ve never been alone together before, which forces them to see their relationship in a whole new light. Suddenly realizing that neither of them knows each other as well as they’d though, they drift apart on their trip, leaving Bergman to explore significant cultural landmarks that soon begin infiltrating and shaping her world view, while her husband takes off to Capri and explores the possibility of passionate feelings with another. This culminates in an incredibly moving final sequences of detachment and reconciliation that navigates from an excavation site at Pompeii to a parade on the streets of Naples.

While Stromboli feels the least successfully cohesive of these three films, taken together, this a trilogy of geographically themed exercises in detachment and the discovery of one’s true self. Physical and emotional journeys are brought onto characters by unstoppable and unseen forces exacted by war, death, and money. Rossellini, of course, was known, along with De Sicca, as a forefather of neorealism, and his Voyage trilogy, while still utilizing these techniques, was written off as a series of melodramatic vehicles crafted specifically for fallen angel and muse Bergman. This trio of films are neither simple melodramas nor complete embodiments of the neorealism of previous Rossellini titles. If Stromboli is painstakingly obvious with its themes (a stunningly filmed sequence involving the capture of tuna in the fishermen’s nets evokes a cycle of life and death as surely as it serves as metaphor for the displaced women stuck in the Farfa camp from which Antonio took Karin) and equally obnoxious with Bergman’s ascent of the volcano as she cries in anguish to her god, Journey To Italy is a delicately and delightfully crafted exploration of relationships, complacency, and the evocation of our connections to our anthropological roots. And while The Flowers of St. Francis certainly has its champions with its lightly comedic vignettes focused solely on the monks following the titular saint (this is also Rossellini’s most explicitly religious film), it is Europe ’51, where Bergman becomes martyr incarnate, that beautifully expresses issues of empathy and class divisions that suffocate humanity. Bergman utters one of her most deliciously melancholy lines ever committed to film here as she explains her newfound compassion for others: “Love for others is born out of the hate I feel for myself.”

Disc Review

Criterion has included the Italian language versions of these titles, and besides being flourishes for the purist, these versions also highlight the beautiful restoration that was able to be administered to the English language versions. Not only has Criterion remastered three magnificent and previously difficult to see titles, this set includes an amazing set of extra features and a beautiful booklet with featured essays from Richard Brody, Dina Iordanaova, Dagrada, Fred Camper, and Paul Thomas (as well as letters from Bergman and Rossellini and interviews).

A 1998 documentary, Rossellini Under the Volcano, returns to Stromboli fifty years of the making of the film, and a new interview with film historian Elena Dagrada comments on the different versions of Europe ’51. A behind the scenes look at the Rossellini clan during the making of Journey To Italy is of minor interest, but a 2013 interview with Isabella Rossellini and her twin Ingrid is not to be missed. A new interview with critic Adriano Apra is also quite compelling, as is a 60 minute documentary Apra made in 1992 focused on the work of Rossellini.

A new visual essay from James Quandt, Surprised By Death, focuses on historical and artistic themes of the trilogy, while Living and Departed, a visual essay from Rossellini scholar Tag Gallagher is extremely astute and admirably realized. A 1995 documentary narrated by Bergman’s eldest daughter, Pia Lindstrom, Bergman Remembered, is a loving tribute to her late mother. But perhaps most exciting of all are two shorts Criterion includes in the set, including Guy Maddin’s 2005 My Dad is 100 Years Old, in which Isabella Rossellini plays all the roles in an episode of her father’s life, and a 1952 short from Rossellini called The Chicken, a comedic exercise starring Bergman.

Final Thoughts

Criterion’s restoration and presentation of these three Rossellini/Berman films is not to be missed. A resurrection of titles that seem to have drifted to the outskirts of the cinematic subconscious, to behold all three in quick succession is a haunting delight. Even if Stromboli often feels like an exercise of infatuation, we see a veritable transformation of Bergman’s visage between their first and second venture, her beauty crystallized into her melancholy cheekbones by Europe ’51. Miscommunication and marital unhappiness are distilled no more succinctly than in Journey To Italy, a couple oh-so-close yet equally far away. As the extra features also indicate, these films are heavily informed and influenced by the relationship of Bergman and Rossellini as well, and knowledge of their own trials and travails is unmistakable, only adding to the immense poignancy of Journey, where a Pompeii excavation reveals the outlines of two people, a man and woman, who died clutching each other as they were consumed by fiery ash. Time is short and should be enjoyed, remarks a snarky George Sanders earlier on in Journey and it’s hard to imagine a better way to spend it then experiencing this remarkable trilogy.