The Safety of Objectivism: Corbet Unleashes the Survival Instinct of Rational Egoism

Broken into two parts and an epilogue, we follow the journey of Hungarian architect Laszlo Toth (Brody) as he enters post WWII America from the years 1947 to 1980. In his disorienting arrival, he heads to Philadelphia where he is greeted by his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), who owns a furniture store with his wife. They allow Laszlo to live in a store room, and he designs furniture for them (although Attila’s wife Rebecca seems none too interested in assisting the Jewish foreigner, family or not, seeing as she’s had her husband convert to Catholicism). Laszlo patiently awaits for the arrival of his wife Erzsebet (Felicity Jones) and his mute niece Zsofia (Raffey Cassidy), who are both still stuck in Europe. A nose injury he incurred during the war has led him down the dark path of heroin addiction, which no one seems to notice.

When Harry (Joe Alwyn), the son of a wealthy business magnate, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) commissions Attila and Laszlo to redesign his father’s beloved library on their palatial estate, a significant opportunity goes up in flames. It turns out Harrison doesn’t like surprises, and both men are fired without being compensated for the work or materials. Attila believes this has brought shame on his business, leading Laszlo to room in a church shelter alongside a new friend, Gordon (Isaac De Bankole), who is also addicted to heroin. Working in a coal plant, Laszlo is sought out by Harrison, who has fallen in love with his new library. And now, he offers Laszlo the second opportunity of a lifetime, to build a massive community center which will include a gym, pool, library and chapel, all interconnected in a building dedicated to his dead mother. However, Laszlo’s best laid plans go awry.

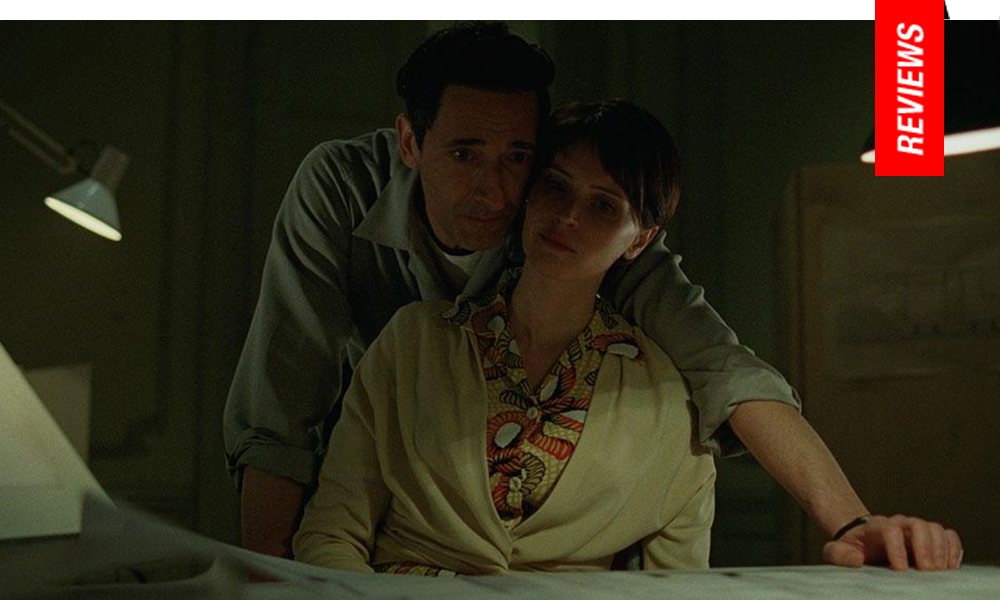

The title’s double meaning works quite exceptionally. Literally, Laszlo is ‘the brutalist,’ specializing in a specific style of functional architecture popularized in the 1950s and 1960s, which, as the film posits, he was already invoking before the war. In the film’s language, his structures utilize nothing superfluous—everything is practical, and, therefore, will survive the mercurial ebb and flow of societal tastes. It is also a word which means ‘cruelty and savageness,’ suggesting it also refers to not only the capitalist elites but all those who complicity participate in upholding a culture predicated on hierarchical imbalance. Brody, who won his Academy Award for portraying a Holocaust survivor in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002), is equally anguished here, impressively speaking Hungarian and accented English. He’s certainly a far cry from Rand’s Howard Roark, a survivor whose resiliency is bolstered by his passion. He’s joined by Felicity Jones as his ailing wife, a journalist who is also a borrowed template from Rand. In the ever quotable text of Rand, together they exemplify the sentiment “No happy person can be quite so impervious to pain.” Both Brody and Jones impress with their performances, requiring them to speak Hungarian. They’re juxtaposed by a larger-than-life Guy Pearce as a pretentious, mercurial entrepreneur unable to handle conflict of any kind, and ruling his homegrown kingdom like a stern despot.

Working once again with DP Lol Crowley, who employs similar roving sequences here as in Vox Lux whilst the stylized opening credits crawl across the screen, Corbet turns his first sacred symbol on its head with an upside down and sideways shot of the Statue of Liberty. Laszlo crawls from the belly of a boat with the camera chaotically following, similar to the visual scheme of Son of Saul (2015). Later, we’ll also see an inverted cross reflected through Laszlo’s monolithic design, eventually confirmed to also be modeled after the concentration camps both he and his wife survived. It’s a clear statement of the upside down world being occupied, a world of populism cloaked in a transparent sheen of hollow words.

Across Corbet’s filmography as director, a pattern of interconnected themes begins to emerge, with his exceptional Sartre inspired debut The Childhood of a Leader (2015) to the pop culture grafted Faustian nightmare Vox Lux (2018), all literary endowed tragedies featuring compromised protagonists pursuing a vision which will define them but prove to ruinous to themselves and others. In the haunting final words spoken in The Brutalist, which also encapsulates Rand’s sensibility, it is indeed, ‘the destination and not the journey’ which matters, highlighting the importance of the intended actuality, the achievable goal instead of a placating sentiment which holds us all in the treading anxiety of suspense rather than the climactic, orgasmic end point we all actually desire. If there’s anything which hits on a sort of brilliance, it’s how well a written theme in the film’s epilogue, “The Past is Present,” utilizes this. Prizing the journey over the destination absolves us from ever having to reach our desired goals. And the eternal dysfunctional realities glaringly evident, and, for whatever explanation or reason, we still decide not to see, are what keep us conditioned to stay invested in a distracting chaos.

With an overture and a fifteen-minute intermission, Corbet hearkens back to a grand tradition, now nearly extinct, of what cinema could and should be. Like the titans of the New American Cinema movement, rarely courted by a select handful of contemporary American directors who have been allowed the opportunity to take similar narrative risks. In many ways, this is a film which we would have expected from Paul Thomas Anderson, particularly after his 2012 title The Master.

Corbet aligns the architectural aspects with the similar process of filmmaking. A film is also built, and often, a director’s vision is often compromised by whatever corresponding powers are required to make this collective effort. The Brutalist, is, in essence, a slickly paced saga about survival, compromise, and a fulfillment which may never come, or at least be appreciated until it’s too late for its creators to enjoy. But then, maybe this is the steel nerve underlying the film’s themes—to survive beyond the fickle desires of the popular, sometimes horrific ‘trends’ sanctioned by the masses.

Reviewed on September 1st at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 215 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆