The Safety of Objectivism: Corbet Unleashes the Survival Instinct of Rational Egoism

“The hardest thing to explain is the glaringly evident which everybody has decided not to see,” so says the heroic protagonist of Ayn Rand’s sensational 1943 novel The Fountainhead, an individualist archetype she intended as “the man that man should be…above all—the man who lives for himself.” It was a tome in which Rand began to craft her controversial theory of Objectivism, which, among its tenets, suggests morality is wholly independent of human knowledge. Filmmaker Brady Corbet, with his third feature, the masterful saga The Brutalist, finds himself, along with co-writer and partner Mona Fastvold, freely inspired by Rand’s iconic novel (and no, their achievement is certainly not akin to the output of ‘second-rater’ mentality skewered by Rand, those collective gatekeepers who squash genius in their contradictory crusade to uphold the greater good). Instead, Corbet and Fastvold pay homage to Rand by creating a trajectory which mulls over similar territory but with characterizations defined by extreme experiences, moving well beyond the propaganda of an inherent philosophical agenda. While Rand’s rhetoric has long been adopted by the far-right, with ideas and statements cherry picked, much like the Bible, for warped causes, she also has insightful understanding of human behavior and mob mentality. Corbet’s narrative focuses on an architect, a Hungarian Jew played quite remarkably by Adrien Brody, who’s survived the Holocaust, and lucky enough to make it to New York City after liberation from Nazi Germany. Once there, he quickly sees there’s no such thing as the American Dream, where humanity has been eroded by elitism, consumerism, and xenophobia so fever pitched it screams.

“The hardest thing to explain is the glaringly evident which everybody has decided not to see,” so says the heroic protagonist of Ayn Rand’s sensational 1943 novel The Fountainhead, an individualist archetype she intended as “the man that man should be…above all—the man who lives for himself.” It was a tome in which Rand began to craft her controversial theory of Objectivism, which, among its tenets, suggests morality is wholly independent of human knowledge. Filmmaker Brady Corbet, with his third feature, the masterful saga The Brutalist, finds himself, along with co-writer and partner Mona Fastvold, freely inspired by Rand’s iconic novel (and no, their achievement is certainly not akin to the output of ‘second-rater’ mentality skewered by Rand, those collective gatekeepers who squash genius in their contradictory crusade to uphold the greater good). Instead, Corbet and Fastvold pay homage to Rand by creating a trajectory which mulls over similar territory but with characterizations defined by extreme experiences, moving well beyond the propaganda of an inherent philosophical agenda. While Rand’s rhetoric has long been adopted by the far-right, with ideas and statements cherry picked, much like the Bible, for warped causes, she also has insightful understanding of human behavior and mob mentality. Corbet’s narrative focuses on an architect, a Hungarian Jew played quite remarkably by Adrien Brody, who’s survived the Holocaust, and lucky enough to make it to New York City after liberation from Nazi Germany. Once there, he quickly sees there’s no such thing as the American Dream, where humanity has been eroded by elitism, consumerism, and xenophobia so fever pitched it screams.

Broken into two parts and an epilogue, we follow the journey of Hungarian architect Laszlo Toth (Brody) as he enters post WWII America from the years 1947 to 1980. In his disorienting arrival, he heads to Philadelphia where he is greeted by his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), who owns a furniture store with his wife. They allow Laszlo to live in a store room, and he designs furniture for them (although Attila’s wife Rebecca seems none too interested in assisting the Jewish foreigner, family or not, seeing as she’s had her husband convert to Catholicism). Laszlo patiently awaits for the arrival of his wife Erzsebet (Felicity Jones) and his mute niece Zsofia (Raffey Cassidy), who are both still stuck in Europe. A nose injury he incurred during the war has led him down the dark path of heroin addiction, which no one seems to notice.

When Harry (Joe Alwyn), the son of a wealthy business magnate, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) commissions Attila and Laszlo to redesign his father’s beloved library on their palatial estate, a significant opportunity goes up in flames. It turns out Harrison doesn’t like surprises, and both men are fired without being compensated for the work or materials. Attila believes this has brought shame on his business, leading Laszlo to room in a church shelter alongside a new friend, Gordon (Isaac De Bankole), who is also addicted to heroin. Working in a coal plant, Laszlo is sought out by Harrison, who has fallen in love with his new library. And now, he offers Laszlo the second opportunity of a lifetime, to build a massive community center which will include a gym, pool, library and chapel, all interconnected in a building dedicated to his dead mother. However, Laszlo’s best laid plans go awry.

The title’s double meaning works quite exceptionally. Literally, Laszlo is ‘the brutalist,’ specializing in a specific style of functional architecture popularized in the 1950s and 1960s, which, as the film posits, he was already invoking before the war. In the film’s language, his structures utilize nothing superfluous—everything is practical, and, therefore, will survive the mercurial ebb and flow of societal tastes. It is also a word which means ‘cruelty and savageness,’ suggesting it also refers to not only the capitalist elites but all those who complicity participate in upholding a culture predicated on hierarchical imbalance. Brody, who won his Academy Award for portraying a Holocaust survivor in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002), is equally anguished here, impressively speaking Hungarian and accented English. He’s certainly a far cry from Rand’s Howard Roark, a survivor whose resiliency is bolstered by his passion. He’s joined by Felicity Jones as his ailing wife, a journalist who is also a borrowed template from Rand. In the ever quotable text of Rand, together they exemplify the sentiment “No happy person can be quite so impervious to pain.” Both Brody and Jones impress with their performances, requiring them to speak Hungarian. They’re juxtaposed by a larger-than-life Guy Pearce as a pretentious, mercurial entrepreneur unable to handle conflict of any kind, and ruling his homegrown kingdom like a stern despot.

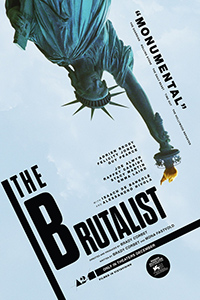

Working once again with DP Lol Crowley, who employs similar roving sequences here as in Vox Lux whilst the stylized opening credits crawl across the screen, Corbet turns his first sacred symbol on its head with an upside down and sideways shot of the Statue of Liberty. Laszlo crawls from the belly of a boat with the camera chaotically following, similar to the visual scheme of Son of Saul (2015). Later, we’ll also see an inverted cross reflected through Laszlo’s monolithic design, eventually confirmed to also be modeled after the concentration camps both he and his wife survived. It’s a clear statement of the upside down world being occupied, a world of populism cloaked in a transparent sheen of hollow words.

Across Corbet’s filmography as director, a pattern of interconnected themes begins to emerge, with his exceptional Sartre inspired debut The Childhood of a Leader (2015) to the pop culture grafted Faustian nightmare Vox Lux (2018), all literary endowed tragedies featuring compromised protagonists pursuing a vision which will define them but prove to ruinous to themselves and others. In the haunting final words spoken in The Brutalist, which also encapsulates Rand’s sensibility, it is indeed, ‘the destination and not the journey’ which matters, highlighting the importance of the intended actuality, the achievable goal instead of a placating sentiment which holds us all in the treading anxiety of suspense rather than the climactic, orgasmic end point we all actually desire. If there’s anything which hits on a sort of brilliance, it’s how well a written theme in the film’s epilogue, “The Past is Present,” utilizes this. Prizing the journey over the destination absolves us from ever having to reach our desired goals. And the eternal dysfunctional realities glaringly evident, and, for whatever explanation or reason, we still decide not to see, are what keep us conditioned to stay invested in a distracting chaos.

With an overture and a fifteen-minute intermission, Corbet hearkens back to a grand tradition, now nearly extinct, of what cinema could and should be. Like the titans of the New American Cinema movement, rarely courted by a select handful of contemporary American directors who have been allowed the opportunity to take similar narrative risks. In many ways, this is a film which we would have expected from Paul Thomas Anderson, particularly after his 2012 title The Master.

Corbet aligns the architectural aspects with the similar process of filmmaking. A film is also built, and often, a director’s vision is often compromised by whatever corresponding powers are required to make this collective effort. The Brutalist, is, in essence, a slickly paced saga about survival, compromise, and a fulfillment which may never come, or at least be appreciated until it’s too late for its creators to enjoy. But then, maybe this is the steel nerve underlying the film’s themes—to survive beyond the fickle desires of the popular, sometimes horrific ‘trends’ sanctioned by the masses.

Reviewed on September 1st at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 215 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆