Mighty Clichéd: Goodstein’s Debut a Muted Effort We’ve Seen Before

Oh the glorious 1970’s, how we love to explore the vaguely outlined state of mind evoked in thee. Debbie Goodstein jettisons us there for her debut, Mighty Fine, a singularly ineffective and indistinct coming of age tale that moonlights as a character study of (what we’re supposed to assume is) the now extinct patriarchal breadwinner. The trouble is, Debbie, what you’ve given us coasts by solely on good intentions. And we all know what road is paved with those.

Oh the glorious 1970’s, how we love to explore the vaguely outlined state of mind evoked in thee. Debbie Goodstein jettisons us there for her debut, Mighty Fine, a singularly ineffective and indistinct coming of age tale that moonlights as a character study of (what we’re supposed to assume is) the now extinct patriarchal breadwinner. The trouble is, Debbie, what you’ve given us coasts by solely on good intentions. And we all know what road is paved with those.

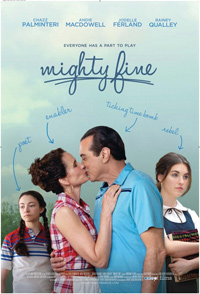

The film opens with the Fine family relocating from Brooklyn, where Joe Fine (Chazz Palminteri) was born and raised, to New Orleans for economic purposes. Joe runs a fabric company, Mighty Fine Fabrics, with its headquarters based out of New Orleans. Due to the harsh economy, Joe wants his be closer to his business, which just happens to be in an area with a lower cost of living, so that he can afford to live as extravagantly as he is used to. Banking on current legislation which would grant him a Southern tax incentive, the only problem seems to be that there are no other Jews in the South, exacerbating elder daughter Maddie’s (Rainey Qualley) already stormy relationship with her domineering father. Young sister Natalie (Ferland) is an aspiring poet, and dreams of being as famous a writer as Anne Frank, seemingly obsessed with the notion since mother Stella (Andie MacDowell) was a young girl like Anne Frank that survived the Holocaust in hiding. With the budding sexuality of older daughter Maddie and Joe’s mob affiliations necessary for keeping his flagging business afloat, his temper flares out of control, endangering the emotional and physical lives of his dependent family. While they all struggle with Joe’s abuse, we’re meant to see that younger daughter Natalie has trouble focusing on her career as a poet in such a hothouse environment.

There’s an insincere atmosphere developed by the amount of “Mighty Fine” things going on, what with a factory, an award winning poem, and a family all literally defined by name as a “Fine.” Sadly, it becomes a running unintentional joke that lubricates the film—there’s nothing mighty or fine about it. Sure, Palminteri gives a decent performance as your typical garden variety patriarch, a bulldog foreman that’s used to treating everyone and everything like his underling, but we’ve seen dear Chazz do this to much greater effect, both at his own direction (A Bronx Tale, 1993) and even in art house memoir masturbation like Dito Montiel’s A Guide to Recognizing Your Saints, 2006. The daughters, as played by child actress turned Twilight support Jodelle Ferland and Rainey Qualley (the real life daughter of MacDowell) are so thinly written and hysterically played (especially Qualley) any screen time permitted fluctuates between snoozeville or camp city. In fact, we often forget that the story’s being told through the eyes of the younger Fine daughter, the dulcet bass of Jeanine Garafalo as an omniscient narrator reminding us every now and again (though, to be honest, the use of Garafalo’s voice as the adult Ferland feels like Mighty Fine is setting itself up as a coming out story). By far, the most bizarre and distracting aspect of the film is Andie MacDowell, playing a Jewish woman who survived the Holocaust in a Christian basement. It’s unfortunate that MacDowell’s simpering accent makes her sound like a Swedish adolescent suffering from a severe overbite.

For a movie that features anti-Semitism, sanitariums, mob ties, a 70’s Elvis performance, and Campbell’s soup poetry contests, this is one dull affair. Awkward transition consisting of black screens that would seem to herald commercials rather than progressive scenes, Mighty Fine is devoid of drama, humor, pathos, or realism. It becomes a quietly tired exercise about a family that’s simply not finely wrought enough to support a film. Sure, it’s oddly funny to watch a dad with anger management try to run his own daughter over with the car he bought her for sweet sixteen, but rather than play with that dark humor, the film deflates lugubriously beneath its own seriousness. “Every family has it secrets. Ours was my father’s rage,” our narrator quips. Bitch, please.