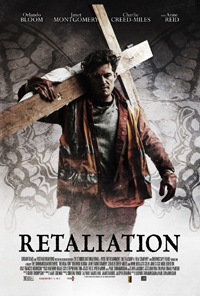

In God They Trust: The Shammasian Bros. Skirt Exploitation in Brooding Character Study

There are certain subjects the mere presentation of which conjures overzealousness parameters and thus automatically ends up feeling exploitative. Curiously, the marketing for the long withheld sophomore film Retaliation from the UK’s Shammasian Brothers, Ludwig and Paul, seems to have taken a route which suggests a problematic approach to a sensitive subject, an adult survivor of sexual abuse at the hands of a priest seeks vengeance on the man who caused the trauma decades later. Starring Orlando Bloom and premiering back in 2017 at the Edinburgh Film Festival, the Shammasian’s have in fact crafted a rather somber, unexpectedly tasteful character study of a conflicted protagonist left all alone to grapple with his significant demons.

There are certain subjects the mere presentation of which conjures overzealousness parameters and thus automatically ends up feeling exploitative. Curiously, the marketing for the long withheld sophomore film Retaliation from the UK’s Shammasian Brothers, Ludwig and Paul, seems to have taken a route which suggests a problematic approach to a sensitive subject, an adult survivor of sexual abuse at the hands of a priest seeks vengeance on the man who caused the trauma decades later. Starring Orlando Bloom and premiering back in 2017 at the Edinburgh Film Festival, the Shammasian’s have in fact crafted a rather somber, unexpectedly tasteful character study of a conflicted protagonist left all alone to grapple with his significant demons.

London based demolition worker Malky (Bloom) is currently working on the destruction of a church, a fact which seems to needle his religious mother (Anne Reid), constantly chiding him for an apparent lack of faith. It seems Malky has had somewhat of a difficult past, having been to prison and never living up to his potential on any front. Though he’s developed some strong bonds with his colleagues, a committed relationship with local bartender Emma (Janet Montgomery) has eluded him. Suddenly, a defining trauma of his past is reawakened when, in the public restroom one day, he spies Father Jimmy (James Smillie), who thirty years prior, raped him. The sighting unleashes a rippling cascade of behavioral issues in Malky, who begins to plot physical vengeance on the priest, a man who has just returned to his parish. But revenge is a dish best served cold, and as the last vestiges of Malky’s limited support network suddenly evaporate, he’s forced to examine the most sensible plan of action to assuage his pain.

Although many may applaud Bloom for giving a ‘career best’ performance, Retaliation, which was initially titled Romans, named for the passage of scripture which saw the short story material titled “Romans 12:20,” it’s not the kind of portrayal which seems calibrated for either awards glory or for a reinvigoration of an actor most commonly associated with Hollywood franchise material, such as The Lord of the Rings and The Pirates of the Caribbean films. Rather, it’s a characterization which is more impressive in showcasing an unexpected range, particularly in two distressing outbursts which elevate the material behind a smattering of cliched sexual hang-ups, those being a confrontation with the corpse of his mother, and then a return to the confessional to contend with James Smillie.

Utilizing extreme close-ups on the agonized Bloom does more for the profundity of the film then the self-inflicted stigmata and some stagey face-offs with Charlie Creed-Miles’s street preacher. If Alex Ferns as Malky’s ride-or-die or Janet Montgomery as the disappointed love interest are never allowed a stand-out moment, the Shammasians at least give Anne Reid a chance to shine subtlety, in some of her finest screen work since another odyssey of taboo sexuality in Roger Michell’s underrated 2003 film The Mother.

The subject of pedophilia is a difficult one to approach, and culturally we tend to celebrate simplified representations of its punishment, such as with the 2015 Oscar winner Spotlight. If studio melodramas often feel a bit overwrought, such as 1996’s Sleepers, documentaries (Deliver Us from Evil, 2006) and foreign films (By the Grace of God, 2019) tend to allow for more comprehensive discussions. Where Retaliation stumbles is in its presentation of James Smillie’s priest, merely presented as a characterless symbol of malevolence whose punishment is a punitive extension of the scripture which inspired this scenario in the first place.

Although fitting and effective, it plays like a move of necessity, an extreme scenario which solves the nagging throb of Retaliation—if a victim can forgive their perpetrator, punishment is still necessary in some shape, way, or form, at least according to proper cinematic standards (as if the invisible hand of the Hays Code and the Catholic Legion of Decency were still censoring our narratives—the villain must always be visibly punished).

The Shammasian Brothers don’t take the darkness of reality to its logical conclusion, opting for the kind of easily won catharsis which doesn’t just usually elude those seeking justice, but suggests there aren’t any alternative options of atonement which would allow for more beneficial conversations regarding how to stop such scenarios before they happen.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆