Reviews

Ghost in the Shell | Review

Dispirited Away: Sanders Succeeds with Somber Live-Action Remake of Cult Manga

The essence of Masamune Shirow’s 1989 cult manga Ghost in the Shell automatically lends itself as fodder for the regurgitated tendencies of the film industry, its plot (and evolution) a mirroring metaphor for its robotic-human hybrid heroine, an as-yet-named portmanteau whose brain (a concept freely exchanged with the notion of a soul or a ghost) has been salvaged when her body could not, and thus becomes retrofitted into a sleek, sexy, and lethally weaponized body. The same concept is easily applied to her character’s various reincarnations onscreen, realized in 1995 in the now iconic anime by Mamuro Oshii (who made a 2004 sequel, as well as a revised version of his original in 2008, Ghost in the Shell 2.0), now receiving a live-action, English language makeover from Rupert Sanders starring a controversially cast Scarlett Johansson. At its worst, its narrative and construction provide evidence for the lack of progression in mainstream cinema, streamlining as it does a flagrantly cerebral and once innovative anime to explore the familiar nexus of organic matter melded to artificial intelligence for the purposes of mankind’s future. And yet, this latest iteration of the girl in the robot is not only visually sumptuous and awesomely transporting (considering what we’ve come to expect from the American CGI machine), but also ceaselessly somber, wonderfully melancholy, and yet remains a compelling exercise in exploring those familiar themes hewn throughout decades of cutting edge science fiction concerning how we define the merits of humanity and the eternal consciousness commonly referred to as the soul.

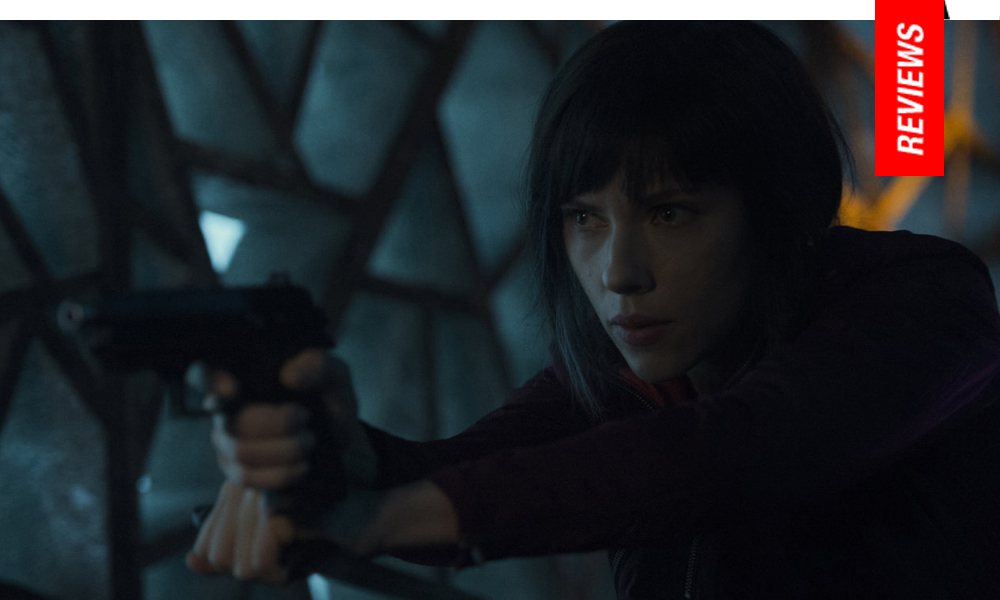

In futuristic metropolis New Port City, Major Mira Killian (Johansson) wakes up to discover her organic body died while her identity has been transplanted into a body (or shell) designed as a weapon for robotics corporation, Hanka. A soothing, motherly scientist, Dr. Ouelet (a warm, empathetic Juliette Binoche) explains the procedure she’s undergone, confirming the Major is the first of her kind, and her success provides a template for the future interactions of humans and artificial intelligence. Assigned as a squad leader to counterterrorism unit Section 9 headed by Aramaki (actor/director “Beat” Takeshi Kitano), the Major and her team become embroiled in the exploits of a mysterious hacker named Kuze (Michael Pitt) who is killing all of the scientists once involved in a secret project for Hanka.

Considering his directorial debut was 2012’s Snow White and the Huntsman, Sanders impresses with this neo-noir electrosynth nightmare, mounting many of the stylized action sequences so famously created by Oshii in his earlier animated versions. However, this PG-13 calibration is a double-edged sword, dialing down the noted sexuality of the cartoon, which does afford the Major some added agency, yet still conforming to Westernized standards of female subjugation. All that’s left is the milky latex cat-suit donned by Johansson’s humorless Major, which sticks out ludicrously in the film’s somber ambience, heavily underlining the notion of her ‘consent,’ or lack thereof, when it comes to determining the deletion of her data (or the uncontested male gaze). The unlawful entry or scanning of one’s mind becomes comparable to the act of a digitized form of rape.

As compared to her previous comparable performances, such as a mysterious alien (the brilliant Under the Skin), a robotic audio interface (Her) or an intelligently enhanced drug mule (Lucy), Johansson strikes the right level of maudlin as the imperious Major (and thankfully there’s no trace of the bemused Black Widow here). True, some discomfort remains concerning her casting, and the specter of Yellow Face is never quite dispelled, but in this futuristic narrative, her whiteness seeps into the fabric in other alarming asides (including how her box office stature seemingly guarantees a greater visibility for the film).

While Oshii’s original blue-eyed cartoon could dismissively be interpreted as an Anglo-Saxan fantasy, the choice of the scientists to deposit these ghosts into the bodies of pretty white bodies (Johansson, Michael Pitt) suggests a technologically advanced interconnectedness where whiteness still reigns supreme (an insidiousness further highlighted by the Major’s interactions with her biological mother). Meanwhile, the international flavor of the supporting cast, including France’s Binoche, Denmark’s Asbaeck, Japan’s Kitano, and Romania’s Anamaria Marinca (in a small but effective role as another scientist for Hanka) lends another melting pot layer to a world informed by eternal data streaming, where humanity is becoming diminished, worn down by the technological advancements designed to flourish after organic matter departs from its own mortal coil. And yet, after all these years, we are still supposedly doomed to the formula of white heteronormative patriarchal standards. So yes, on this particular front, Ghost in the Shell doesn’t manage to be as provocative as its universe should permit.

However, the magnificent design of the imaginary metropolis New Port City channels the vibrant neon, continually restless Los Angeles of Ridley Scott 1982 classic Blade Runner, of which Ghost in the Shell has other thematic similarities regarding humans versus inorganic creatures known as replicants. Also a plus, a trio of screenwriters (Jamie Moss, William Wheeler, and Ehren Kruger) manages to parse the heavy-handed dialogue of the anime into some meaningful exchanges between characters. The Major’s dynamic with Juliette Binoche’s Dr. Ouelet and Danish actor Pilou Asbaeck’s frost-tipped goggle-eyed sidekick results in some startlingly expressive moments for a science fiction film focused on a near emotionless sentient being.

Other references abound, and the ghost of Robocop (1987) and The Terminator (1984) come to mind. As the Major seeks answers to her origins, her alignment with Pitt’s dangerous Kuze recalls everything from a clone gazing upon her failed predecessors in Alien Resurrection (1997) to the troubled monstrosities created by Dr. Frankenstein in the classic James Whale film versions. It’s these memories, or the perception of them, which causes hiccups. Distracted by the notion of an absence at the back of her mind, these visions of a past life become spaces of vulnerability and doubt. “Memories don’t define us,” advises Ouelet, suggesting instead it’s the things we do in the time we have where meaning is found.

Lorne Balfe and the sublime Clint Mansell provide a subdued background score, sampling Kenji Kawai’s original 1995 composition to manage some impressive beats, but it’s mostly overshadowed by the film’s glossy yet vigorous visual designs from DP Jess Hall and production designer Jan Roelfs. For a narrative which asserts it will take beings who are more than human to restore society to its semblance of what we prize as humanity, Sanders’ take on Ghost in the Shell retains the gloomy moodiness of its source, and is more elliptically formulated than most of the dazzling studio tent poles we’re accustomed to.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.