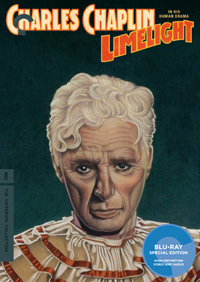

Though he would actually direct other features, including the ill received 1967 A Countess From Hong Kong, wherein Marlon Brando decided to be a mean girl to co-star Sophia Loren, and the neglected A King in New York (1957), many read the 1952 Limelight as Charles Chaplin’s ‘enduring’ final film. An appropriate approximation of his immortal Tramp character after fame has fallen away, the bittersweet tragicomedy wasn’t well-received at the time (though Bosley Crowther raved in The New York Times, hailing the film as “eloquent, tearful, and beguiling with supreme virtuosity”). McCarthyism succeeded in thwarting the film’s distribution, limiting the release to New York City and those labeling Chaplin a Communist picketed screenings where it did play. In the UK, the film’s release was less harried, with newcomer Claire Bloom securing a BAFTA win for Most Promising Newcomer. The film would receive a theatrical release for the first in Los Angeles twenty years later, and thereby secured an Oscar for Best Original Dramatic Score in 1972.

Though he would actually direct other features, including the ill received 1967 A Countess From Hong Kong, wherein Marlon Brando decided to be a mean girl to co-star Sophia Loren, and the neglected A King in New York (1957), many read the 1952 Limelight as Charles Chaplin’s ‘enduring’ final film. An appropriate approximation of his immortal Tramp character after fame has fallen away, the bittersweet tragicomedy wasn’t well-received at the time (though Bosley Crowther raved in The New York Times, hailing the film as “eloquent, tearful, and beguiling with supreme virtuosity”). McCarthyism succeeded in thwarting the film’s distribution, limiting the release to New York City and those labeling Chaplin a Communist picketed screenings where it did play. In the UK, the film’s release was less harried, with newcomer Claire Bloom securing a BAFTA win for Most Promising Newcomer. The film would receive a theatrical release for the first in Los Angeles twenty years later, and thereby secured an Oscar for Best Original Dramatic Score in 1972.

Calvero (Charles Chaplin) is a former clown and vaudeville star that’s long lapsed into obscurity. Producers remark that he’s box office poison, and so he’s forced to re-live his glory days within the confines of his memories and scrapbooks. Stumbling home drunk one day, he smells gas in a neighboring apartment and finds his neighbor Thereza (Claire Bloom), an aspiring ballerina, passed out in the midst of a suicide attempt. He calls a doctor and has her moved to his room where she recuperates while the heartless landlady sublets her room to another. Thereza and Calvero begin to bond, both fostering and nurturing each other’s creative spirit, which allows them to break out of each other’s self-doubts. While Thereza begins to find success, Calvero struggles to recapture it, and becomes more disheartened the more the young girl grows emotionally dependent on him.

Limelight was Chaplin’s first directorial effort in five years, following the underwhelming release of 1947’s Monsieur Verdoux, a film not well received by a majority of critics at the time (it became part of the Criterion Collection in 2013). However, this later title bears a marked resemblance to something like A Star is Born, where two figures within the entertainment industry strike up a relationship while on opposing ends of the fame monster.

For those more familiar with Chaplin’s enduring body of silent cinema, it’s still odd to hear him speak, to direct emotion without the aid of punchy intertitles. Often, his love of sentimentality doesn’t always translate as effectively, and Limelight may avoid schmaltz, but it gets awful close with a belabored finale of convenience. Those enamored with Chaplin’s physicality should definitely enjoy his memorable (and only) onscreen union with fellow silent star Buster Keaton in the film’s third act. One wishes Keaton had been more than an extended cameo, entering his scene bitching about the ‘seems like old times’ mantra trotted out to commiserate with the grizzled performers. The film happens to be one of Claire Bloom’s signature roles, and it’s intriguing to see her so young and emotive. As her gratitude turns to love for Calvero, the film takes on a definite air of melodrama that feels all too familiar. Chaplin plays his saddened clown with a matter-of-factness, and Thereza’s ‘audience rigging’ of his final performance manages to be rather moving. If you’re willing to buy into the film’s sentimental streak, Limelight manages to be unexpectedly bittersweet.

Disc Review:

This new 4K digital restoration is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, and the presentation is remarkably clear and uncluttered. DoP Karl Struss, who also worked on Chaplin’s The Great Dictator nearly goes unnoticed as we focus intensely on Chaplin and Bloom within the confines of his apartment for a great majority of the film. A bevy of extra features are worth checking out, including an outtake that was in the original film’s premiere but later removed by Chaplin.

Chaplin’s “Limelight” – Its Evolution and Intimacy:

Produced by Criterion in 2015, this program features Chaplin biographer David Robinson, exploring the evolution and personal nature of Limelight. Robinson asserts it is the most complex and complicated titles out of all Chaplin’s films, an evolution that took decades. The feature, about twenty minutes, begins with the three month world tour that Chaplin began after the release of Modern Times.

Claire Bloom & Norman Lloyd Interviews:

Criterion conducted interviews with Bloom and Lloyd (from 2012 and 2015, respectively). Bloom recounts her audition in New York, cast as his lead at only nineteen years of age in a fifteen minute segment. Lloyd speaks of his first meeting with Chaplin and recounts his collaboration, also allotted fifteen minutes.

Chaplin Today: “Limelight”:

A twenty six minute segment from 2002, directed by Edgardo Cozarinsky, features interviews with Claire Bloom, Chaplin’s son Sydney Chaplin, and director Bernardo Bertolucci (who speaks very passionately about the film).

Outtake:

An outtake that was in the film’s original premiere but removed before it was distributed worldwide features an old, armless friend of Calvero’s. It’s a brief, four minute sequence.

Archival Audio:

About two minutes of archival audio finds Chaplin reading from Footlights, his novella which provided the basis for Limelight.

A Night in the Show (1915):

Based on the play Mumming Birds, this was Chaplin’s twelfth film directed for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company. Chaplin stars in dual roles, and is accompanied on this disc by a 2014 score by composer Timothy Brock. The feature is twenty five minutes.

The Professor (1919):

Chaplin displays his early fascination in performing fleas with this unfinished short from 1919. It’s about six minutes in length.

Final Thoughts:

Certainly the greatest title from Chaplin’s later period of filmmaking, Limelight plays like a very personal, sincere work from an artist who seems to have accepted the inevitability of changing times and tastes. Sweet, sad, and often amusing, it’s the Tramp’s last great appearance on film, unfortunately maligned by the political shenanigans clouding popular beliefs at the time of its release.

Film:★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc:★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆