“England has always been disinclined to accept human nature,” states a congenial Ben Kingsley, playing a minor role as a doctor in the Merchant-Ivory adaptation of E.M. Forster’s novel, Maurice. The statement is meant as withering consolation to a distressed James Wilby, playing the titular young man in pre-World War I Cambridge who eagerly wishes to cure himself of his homosexuality. Bewilderingly rejecting by his ex-classmate and lover, they’ve grown fearful of discovery and the imprisonment which was wielded upon many queer men in the stifling, conservative period.

“England has always been disinclined to accept human nature,” states a congenial Ben Kingsley, playing a minor role as a doctor in the Merchant-Ivory adaptation of E.M. Forster’s novel, Maurice. The statement is meant as withering consolation to a distressed James Wilby, playing the titular young man in pre-World War I Cambridge who eagerly wishes to cure himself of his homosexuality. Bewilderingly rejecting by his ex-classmate and lover, they’ve grown fearful of discovery and the imprisonment which was wielded upon many queer men in the stifling, conservative period.

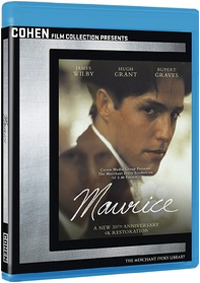

Arriving in the middle of a renaissance of Forster adaptations from the 1980s into the 1990s (kicked off in 1984 by David Lean’s A Passage to India), Ivory’s tackling of a controversial novel, which was published posthumously in 1971, remains quite a feat. Delays in approval to film at Cambridge were cited as due to the establishment’s issue with the quality of this particular Forster text (not the subject matter, of course), and the reputation of its being a ‘lesser’ work from the literary giant (never mind how it’s publication allowed for considerable reinterpretation of his entire canon). Despite the barren and conservative social climate, Merchant-Ivory provoked the impossible, taking home a shared Volpi Cup out of the 1987 Venice Film Festival for its two leads, where Ivory also won the Silver Lion. Now, the title arrives ready for recuperation thanks to a thirtieth anniversary restoration courtesy of the Cohen Media Group, after the title screened at the 2017 Berlin International Film Festival.

In 1909, the father-less Maurice Hall (James Wilby) enters his second year at Cambridge University, which allows him to meet a pair of students whose trajectories will change the course of his own. When the pretentious Lord Risley (Mark Tandy) invites Maurice to the Trinity campus, a chance meeting with Clive Durham (Hugh Grant) evolves into a passionate romantic connection between the two men. But when Risley is disgraced and imprisoned for his sexuality, Clive, fearful of the same fate, makes the decision to break his romantic ties to Maurice and takes a wife. As Maurice tries to cope with the break-up and decide to embrace his sexuality or live the same lie as Clive, an unplanned development with Scudder (Rupert Graves), a servant on the Durham estate, allows Maurice to find love again.

In keeping with all of Merchant-Ivory’s illustrious productions, Maurice adheres to a similar pattern of critiquing social conventions, often which stifle and suffocate its characters. Comparatively, it’s a film which seems less subtle in its approach to conveying the constrictions of Edwardian England, seeing as homosexuality was illegal and a crime punishable by law. Frame of reference was incredibly limited for such a buttoned up, conforming society, as evidenced by Maurice’s breakdown when approaching the family doctor, looking for help and only able to explain his condition by comparing himself to men of a similar ilk. “I’m an Oscar Wilde type,” he declares, referencing the famed author whose trial would give occasion to label the infamous ‘love without a name.’

A sputtering Denholm Elliott (perfectly cast) proffers the only advice he knows to give, urging the young man to find a beautiful woman and forget all about it. Ivory and co-scribe Kit Hesketh-Harvey open the film beautifully with a bit of sexual education, a blustering Simon Callow taking preadolescent Maurice under his wing on a beach excursion, drawing female and male anatomy out in the sand and explaining the act of procreation in the vaguest of sanitized terms, ending his lesson by confirming the gift of parenthood to be the watermark for ‘life’s chiefest glory.” It’s a wink-nudge moment for those in the know on the film’s subject matter, and a moment of irony used to predicate a later re-appearance of Callow’s character when a matured Maurice is in the throes of a romantic interlude with a younger man who belongs to a lower class.

And for all the film’s obviousness, it’s the notion of ‘class,’ these parameters of privilege which underline every single one of Merchant-Ivory’s productions, which receives its most dour administration from the duo. Brilliantly outlining the codification of homosexuality into hushed reference (one can’t seem to get through more than a handful of scenes before some contestable reference to those condemnable Greeks and “their unspeakable vice,” or their culture of ruins which can only be visited for “pleasure,” is disdainfully remarked upon), in denying its existence in the arts by conveniently skipping over it and refusing to acknowledge its presence, Ivory underlines how the rigid class system contributed to the subjugation of homosexuality.

Maurice’s budding romance with Clive, played with realistic fervor and eventual contempt by James Wilby and Hugh Grant, begins immediately after a classmate (a character later used to exemplify the consequences of those daring enough to seek creature comfort outside the safety of their class bubble) grants an innuendo laden invitation to their Cambridge quarters. A bonding experience over a pianola (and lots of apples, that most sinful of fruits) leads to plenty of heavy petting, and discussions on how kissing will lower their emotional bond, something Grant’s Clive assumes woman must not be capable of understanding.

Clive’s eventual choice to choose an oblivious wife (after a mild but treacherous flirtation with Maurice’s sister, Ava) yet keep Maurice heavily involved (platonically, natch) in his circle of friends is a selfish way to keep his object of desire near and a cruel resort to string him along to avoid any scandal. Eventually, passion blooms, albeit uneasily, with Rupert Graves’s servant Scudder, a boisterous youth whose declarations of love are misconstrued by Maurice’s paranoia, his social borne cynicism occluding a possible romance. Tellingly, Scudder’s night time visits to Maurice’s room on the Durham estate are made possible by a ladder allowing him to ascend to the privacy of the upperclassman’s sphere (something Maurice initially declines to traverse when plaintively invited to visit Scudder down in the boat house).

Love and lust comingle dangerously with conceptions of what’s decent between men, a discerning line between baseness and innocent-minded enlightenment allowed through the sphere of fraternity. Ivory concocts an interesting exchange of power through the metaphor of a cricket game, where pitchers, catchers, and who has the other’s best interests in mind is exactingly conveyed.

Several notable actors loom magnificently in the cherry-picked supporting cast—from extras like Jean-Marc Barr and their eventual regular player Helena Bonham-Carter, to Kingsley, Callow, Peter Eyre, and Denholm Elliott. As a pair of mothers, a fretful Billie Whitelaw and a steely Judy Parfitt are figures who can perhaps sense the connection between their sons, but also realize the benefit and discretion available by letting it alone.

Disc Review:

A fantastic new 4K restoration from the original negative and supervised by Ivory and DP Pierre Lhomme, Maurice is presented in 1.66:1 with 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio. Lhomme’s turn of the century England is brought vibrantly to life as the film moves from the monolithic structure of Cambridge to the oscillating estates of its two main characters. A plethora of extra features accompany this new release from Cohen Media Group, one of several successive Merchant-Ivory restorations planned from the distribution label.

The Making of Maurice:

James Ivory and Pierre Lhomme discuss the making of the film in this fifteen minute interview moderate by Gavin Smith with the Cohen Media Group.

Q&A:

Nicholas Elliott moderates this twenty-two minute on-stage Q+A with James Ivory and Pierre Lhomme, which took place at The French Institute Alliance Francaise.

A Director’s Perspective:

This forty-minute conversation between James Ivory and Tom McCarthy (The Station Agent; Spotlight) finds the directors discussing Maurice.

The Story of Maurice:

This half-hour feature finds cast and crew ruminating on the creation of the film and the process of putting it together.

Conversation with the Filmmakers:

James Ivory discusses his interest in E.M. Forster and his approach to adapting Maurice.

Deleted Scenes:

James Ivory provides audio commentary for nearly forty minutes of deleted scenes.

Final Thoughts:

Arguably the most important, and certainly the most daring entry in the Merchant-Ivory canon, Maurice is a lush exploration of identity, passion, and being true to oneself.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆