While he maintained a curiously uneven track record throughout his five decades as a director, Richard Fleischer’s career was speckled with as many underrated gems as camp misfires, which perhaps explains why he’s probably best remembered today for the latter portion of his career, which included the B-grade bombast of Soylent Green (1973) and a couple mid-80s Schwarzenegger vehicles (Conan the Destroyer; Red Sonja). Worse, he was also responsible for that 1980 revamp of The Jazz Singer, a shameless franchise entry with Amityville 3D (1983), and the cringey distinction of adapting Ken Onstott’s controversial Mandingo (1975). Still, he’s an Oscar winner (for the 1947 documentary Design for Death) and Cannes competitor (the 1959 Leopold and Loeb rendition Compulsion), and also the first director to mount an adaptation of Joseph Wambaugh, the famed LAPD detective whose novels provided sensational material for the cinema. Wambaugh’s contemporary would be someone like a Taylor Sheridan (scribe of Sicario, Hell or High Water, and Wind River), and it would be Robert Aldrich’s The Choirboys (1977) and Harold Becker’s The Onion Field (1979) which would conceal his own cinematic legacy.

While he maintained a curiously uneven track record throughout his five decades as a director, Richard Fleischer’s career was speckled with as many underrated gems as camp misfires, which perhaps explains why he’s probably best remembered today for the latter portion of his career, which included the B-grade bombast of Soylent Green (1973) and a couple mid-80s Schwarzenegger vehicles (Conan the Destroyer; Red Sonja). Worse, he was also responsible for that 1980 revamp of The Jazz Singer, a shameless franchise entry with Amityville 3D (1983), and the cringey distinction of adapting Ken Onstott’s controversial Mandingo (1975). Still, he’s an Oscar winner (for the 1947 documentary Design for Death) and Cannes competitor (the 1959 Leopold and Loeb rendition Compulsion), and also the first director to mount an adaptation of Joseph Wambaugh, the famed LAPD detective whose novels provided sensational material for the cinema. Wambaugh’s contemporary would be someone like a Taylor Sheridan (scribe of Sicario, Hell or High Water, and Wind River), and it would be Robert Aldrich’s The Choirboys (1977) and Harold Becker’s The Onion Field (1979) which would conceal his own cinematic legacy.

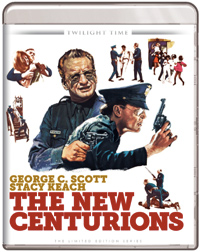

However, Fleischer’s 1972 mounting of Wambaugh’s first novel, The New Centurions, is a bristling little slice of character driven discomfort (albeit from the fashionable side of the oppressor rather than the oppressed). Worthy of recuperation, it hinges on the grisly underbelly to the sort of heroics which defined most films of the era celebrating white, vigilante cops, thanks to iconic staples like Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson. George C. Scott and Stacy Keach headline this script, adapted by Stirling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night, 1967) in a film which tackles racism, homophobia and misogyny instead of depending on the standard cop clichés, all while maintaining a level of complexity in its characterizations.

Scott impresses as a grizzled, weatherworn veteran who ends up inadvertently influencing Keach’s rookie for the worst (over a decade later, we’d see this dynamic sanitized in the opposite direction in something like Colors, and then thrown into hellish reversal of fortune in Training Day), who becomes consumed by a job which was meant to pay his way through school, compromising his marriage (to Jane Alexander) and eventually his sanity. Few films of the period bothered to deal with issues of white supremacy (although, Charles Bronson actually defines the ‘white power structure’ of law enforcement in 1973’s The Stone Killer), much less so effectively as what’s accomplished here.

Roughhewn (a sequence featuring Scott Wilson as a gun shy white cop who accidentally murders an innocent black man is a devastating reminder of how little progress has been made) and gritty, Julie Kirgo points out the importance of the film’s production credits in the essay insert. DP Ralph Woolsey (The Great Santini, 1979), a musical score from Quincy Jones, and production design from Boris Leven (Oscar winner for West Side Story, 1961) are a few of the heavyhitters behind the scenes. But in front of the camera, an impressive supporting cast is on display, including a young Erik Estrada with bit parts from Isabel Sanford, Roger E. Moseley, Ed Lauter, and William Atherton.

Rosalind Cash shows up in the third act as a love interest for Keach, a sympathetic salve for the tortured cop (who is involved in a rather insane predicament when he drunkenly accosts a desperate white woman). Of note, Cash famously served as the love interest for Charlton Heston in the more famous genre film The Omega Man the year prior (which more-or-less depicted interracial relationships as a by-product of the post-apocalypse), but here provides the film with one of its infrequent yet blistering signs of hope. The New Centurions, along with his 1971 10 Rillington Place, is one of Fleischer’s best works.

Disc Review:

Twilight Time resurrects The New Centurions in 2.35:1 in its signature limited edition release (3,000 units) with 1.0 DTS-HD Master Audio. Picture and sound quality are effective in this transfer. As per usual, the label offers an isolated music track of the film’s score, while actor Scott Wilson and film historian Nick Red offer an optional audio commentary track, while a second track featuring film historians Lee Pfeiffer and Paul Scrabo is also available.

Film Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆